As the summer months are heating up, so too are Americans’ appetites for dining out, going to the ballpark and attending multiday music festivals — activities almost unimaginable a year ago.

Recent findings from a Morning Consult survey concluded that 66% of Americans would feel safe dining out at restaurants, compared to last year, when that figure never rose above 42%.

Entering July, most mask mandates and other COVID-19 restrictions have been lifted, much to the relief of restaurants and other hospitality businesses struggling to make ends meet.

Even California, the state with some of the tightest restrictions, has mostly reopened its economy. Disneyland Park in Anaheim reopened on April 30 after a 13-month hiatus, and sporting events, such as Los Angeles Dodgers and Clippers games, are operating close to full capacity.

In terms of freight, this summer is ripe with opportunities, though getting back into the pre-pandemic swing of things may not be as easy as getting back on a bicycle.

“Everyone’s in for a whirlwind,” said Joe Amici, director of consolidation at Echo Global Logistics, noting that the past year has been marked by sluggish volumes for many food service distributors, such as suppliers of restaurants and culinary schools.

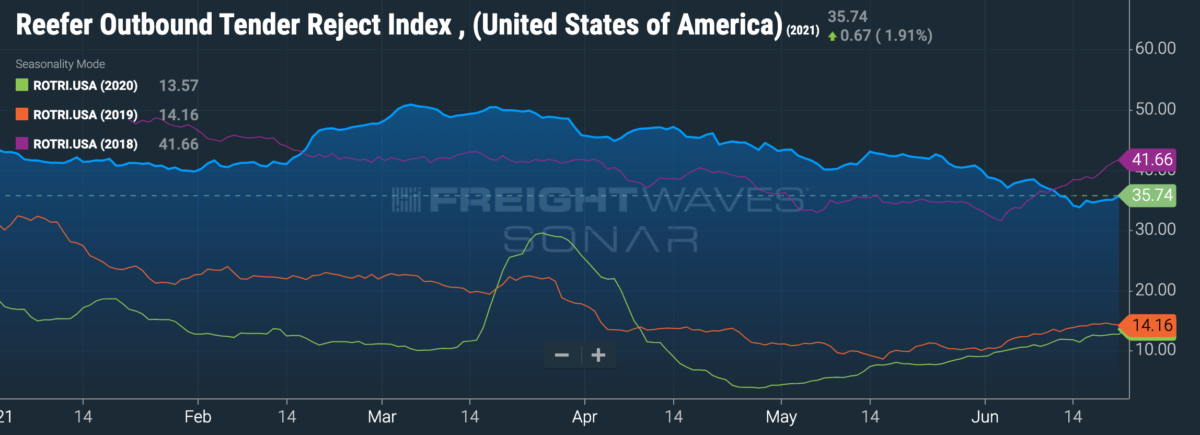

2018: Purple 2019: Orange 2020: Green 2021: Blue

Findings in a recent Echo white paper on a study conducted in conjunction with FreightWaves expounded on the industry’s difficulty sourcing reefer capacity. FreightWaves’ Outbound Tender Reject Index shows the extent of the tightness that has persisted since last fall, with rejections hovering above levels seen amid 2018’s infamous capacity crunch.

It’s going to be a challenge for food service providers to keep up with the reopening of America, especially for those servicing the restaurant industry after a lackluster year. “The food service industry went from a labor surplus and vacant warehouse space to a labor shortage and not nearly enough space,” Amici said.

He alluded to the pandemic’s cold chain lopsidedness: Exorbitant demand kept grocery suppliers on their feet but brought work to a trickle for restaurant suppliers.

“Over the past year, there’s no doubt that a food service distributor probably had excess capacity and space in their warehouse. But that’s going to flip very quickly if it hasn’t already; it’s going to flip to the opposite, which will result in long unload times due to a lack of labor on the dock or delayed deliveries on local trucks to restaurants,” Amici said.

No one could have anticipated the pandemic or its effects on supply chains, and Amici faults no food service provider for struggling in the past year, suggesting that all industries were blindsided. However, he said a diversification of services is perhaps the key lesson a food service provider can learn from the pandemic, explaining that companies primarily servicing culinary schools and restaurants, for instance, could look for a third type of vertical that’s not as vulnerable to sudden shutdowns.

“From a service standpoint, it seems that we’re going to be in a very tight market for some time, along with a driver and a supply shortage,” Amici said, arguing that alongside drivers, warehouse and kitchen staff shortages are becoming even more problematic for supply chains.

Dave Ardell, SVP of carrier operations at Echo, believes it’s still up for debate whether the restructuring of supply chains to service customers directly (as seen with meat and produce suppliers) will remain the new normal. After all, many long-standing freight networks were disrupted, and he suggested it may take some time for supply chains to return to their pre-pandemic state.

Ardell said capacity could be further drained this summer if retailers decide to pull forward inventory ahead of the holiday rush.

“The fight for capacity is going to continue; it may intensify as some of these short-term “new normals” get thrown out the window,” Ardell said.

“You can expect Echo to find capacity when others struggle — and to find it at a fair market rate,” Ardell added.

“Plan ahead as far as you can,” Ardell urged food suppliers. “Most companies place purchase orders pretty early, so use that lead time to get that information over to your carrier partners.”

Ardell said to allocate a larger budget to accommodate detention costs, as he expects load times and driver holdups to increase in light of recent warehouse labor shortages.

“While I can’t predict how long the average unload time will be at any given distribution center in three, six or 12 months, I can say with confidence that I think it’ll probably be longer than what we’ve experienced in the last year,” Ardell said.

Click for more FreightWaves content by Jack Glenn.

More from Echo: