The supply of freighter aircraft continues to expand to record levels even as the air cargo market decelerates, raising questions about whether leasing companies and cargo operators are creating more capacity than can profitably exist once shipping growth returns to normal.

Analysts say there are more all-cargo aircraft in active service than ever, but their utilization rates are starting to recede from last year’s peak. As the global economy slows and cargo rates drop, older aircraft that were kept in service when capacity was at a premium could quickly be mothballed.

“There is going to be a lot more impetus on airlines to begin retiring these aircraft, particularly as they come up for engine checks and heavy maintenance on their fuselage and landing gear,” said Neel Jones Shah, head of global airfreight at Flexport, during a recent company webinar.

Annual growth in freighter capacity measured by total available payload increased 6% during the last three years, double the rate before the COVID-19 crisis and the fastest in two decades, according to analysis by McKinsey & Company and aviation analytics firm Cirium.

More than 340 extra main-deck freighters — an 18% increase — took to the skies since the start of the pandemic, when passenger belly capacity disappeared along with travel and every capable aircraft was brought out of storage in response to booming demand for shipping. New builds from Boeing and a slew of passenger-to-cargo conversions also contributed to the fleet’s growth. There are now about 2,200 dedicated cargo jets in service around the world, data compiled by Cirium shows.

Capacity growth would have been greater if Russian-operated freighters hadn’t exited the market last spring due to Western sanctions over the invasion of Ukraine. The most significant shutdown was of AirBridgeCargo, which operated 17 Boeing 747s plus a 777. Both are large widebody jets.

Another factor behind the larger freighter fleet was the record low number of retirements the past couple years for aircraft that exceeded their useful life as airlines took advantage of extremely high demand and yields caused by supply chain disruptions. Since 2020, only about 15 to 20 freighters have been retired per year, compared to an average of 70 since 2004, according to McKinsey.

A record number of cargo jets — more than 500, or 15% of the fleet — are over 30 years of age by Cirium’s count.

But after 18 months of blockbuster air cargo volume and revenues, shipping demand year to date through September is 2.4% below last year and a tick below 2019 levels. Inflation, high inventory levels, the Ukraine war and COVID lockdowns in China have cooled demand each month since March while more cargo-capable passenger aircraft are reintroduced to support a resurgence in travel.

The downward trend continued in October, with cargo tonnage down 16% from a year ago and rates down by a quarter, according to WorldACD and the Freightos Air Index, respectively.

McKinsey forecasts cargo demand will grow 2.5% to 3% per year through 2031, compared to Boeing and Airbus projections of 4.1% and 3.2% compound annual growth over 20 years. Airbus says the air express sector will grow faster — 4.9% — than general cargo.

Meanwhile, McKinsey expects cargo capacity to annually increase 4.5% in the next decade to the point that the mix between freighters and passenger belly space returns near the historical 50/50 balance versus today’s 70% to 30% ratio.

Aftermarket freighter bubble?

Factory freighters augment the global freighter fleet each year, but the main source of new assets is the conversion market.

Cirium estimates more than 40 factory-built freighters will be delivered this year, led by the Boeing 767 and 777. Those planes are scheduled to end production after 2027 due to international emissions rules that the U.S. has agreed to follow. The analytics firm counts nearly 100 orders for new freighters this year, an all-time high.

Airbus plans to start producing the large A350 freighter in 2025 in an attempt to revive a stillborn freighter program from a decade ago, while Boeing (NYSE: BA) will introduce a new version of the 777 freighter named the 777-8. So far, the manufacturers have 74 firm orders from 10 customers for the new planes.

Meanwhile, investors and cargo airlines are trying to capitalize on predicted growth in cargo demand and the e-commerce phenomenon by acquiring a massive amount of aftermarket freighters — used passenger planes completely renovated to carry containers in the cabin. Converting a previously owned aircraft is much quicker and cheaper than buying a freshly manufactured one.

Conversion specialists are on track to set another record this year with 190 overhauled airframes, up from a record 120 conversions last year and triple the amount completed in 2019, based on data from multiple research firms. The number of passenger-to-freighter conversions has steadily increased at a 9% compound annual growth rate from 2010-21, driven by demand for standard-size freighters best suited for regional package networks.

Conversion activity has fluctuated between 60 to 70 units per year for the past three decades, with spikes of about 90 aircraft in 2006-07 and 2018.

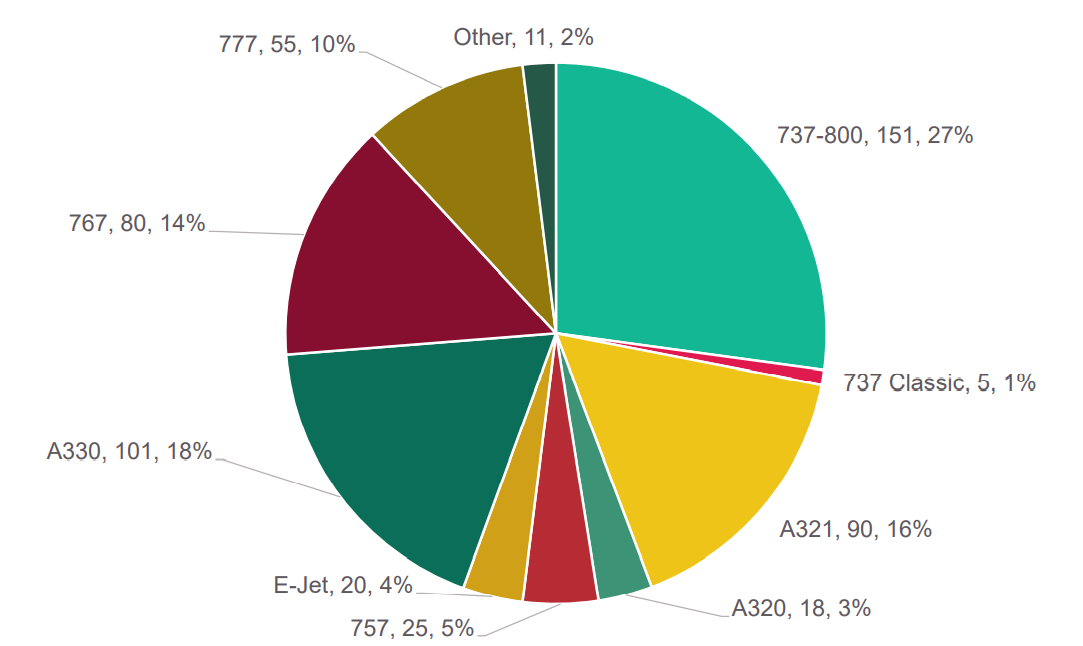

As of July, there were 150 orders to modify Boeing 737-800 aircraft, according to a presentation by Ludwig Hausmann, a partner at McKinsey, at a recent cargo symposium in London. Orders are also escalating for the new Airbus A320/321, a relatively new competitor to the 737-800, and the A330, a medium widebody.

The backlog for conversion work is more than 550 units and heavily skewed to single-aisle aircraft.

Converted and production freighters currently on order represent more than 30% of the active freighter fleet, said Hausmann. The freighter backlog includes about 100 widebody orders scheduled for delivery between 2023 and 2026.

Aerospace firms that redesign aircraft for cargo are adding more production lines by partnering with repair and overhaul shops around the world that do the work of stripping out cabin interiors, installing large cargo doors and making structural changes to load heavy cargo where passengers once sat.

Conversion orders, and capacity, could accelerate with next year’s expected debut of a 777 converted freighter. Israel Aircraft Industries says it already has more than 50 orders for modified 777-300s. Mammoth Freighters, a new U.S. rival, claims it has 29 firm orders for its 777-200 and 777-300 conversion kit. The company could begin commercial production in 2023 or 2024, depending on when its design is approved by the Federal Aviation Administration.

Cirium projects that as many as 220 converted freighters could be produced in 2023, “raising concerns whether we’re entering a bubble” for conversion investment, said Daniel Hall, a senior valuation consultant at Cirium’s consulting arm, during an October webinar.

The 737-800 continues to dominate the passenger-to-freighter market, with 52 produced through the end of October, compared to 53 last year, raising the risk of oversupply, said market intelligence and appraisal specialist IBA. The number of commitments for the Airbus A321 converted freighter, a 737-800 competitor with the ability to succeed the 757, is also growing. There are only 10 active aircraft, but 44 pending conversion.

Fortune Aviation Services warned last spring there could be too many small freighters for several years. It could take years for a capacity correction to work through the industry, the consulting firm said.

Freighter deliveries typically peak two to four years after strong demand growth, Hausmann said, and could reach their apex in 2023 because of the faster time to market for conversions. AeroDynamic Advisory earlier this year forecast conversion activity would top off in 2024 or 2025.

Cirium’s 20-year forecast calls for 1,600 to 2,000 conversions, which would represent a slower annual production rate than today but one higher than the historical average.

Aviation Week Network estimates almost 2,000 dedicated freighter aircraft of all types will be added over the next 10 years, a significant increase from its prior year analysis. The fleet is going to grow at a 1.7% compound annual growth rate but total fleet capacity based on volume will increase 3.7% per year, indicating that operators will lean more to larger aircraft.

Lessors dive in

The predominant acquirers of repurposed cargo jets these days are leasing companies trying to generate additional returns on aircraft they can’t place back in passenger service since the COVID crisis. There are at least 18 lessors managing fleets of converted freighters in the narrowbody sector alone, according to Cirium.

So far, pivoting to cargo aircraft has been a good choice for lessors. The value of a 737 built in 2004 fell 31% during the pandemic and has only partially recovered, while a 737 converted freighter has increased in value by 7%, Hall said.

The market value compared to a hypothetical base value is at its highest point in over 20 years. Narrowbody freighters are almost 20% higher than base value on a weighted average basis, while widebodies are almost 40% higher, according to Cirium.

Analysts say airlines are likely to start retiring aging aircraft as the market normalizes and that many new freighters will now be for replacement, minimizing the potential for substantial overcapacity.

According to McKinsey, 5% of freighter capacity will be edged out the market if yields decline or fuel costs remain high because the planes won’t be economical to operate.

The math suggests capacity will enter the market faster than it exits in the next couple of years, assuming about 50 factory deliveries and 200 conversions against 40 to 50 retirements. But Hall said retirement activity could pick up pace because of the fleet’s age and the opportunity to improve efficiency.

“We do expect the market to return to some sort of equilibrium later this decade,” he said.

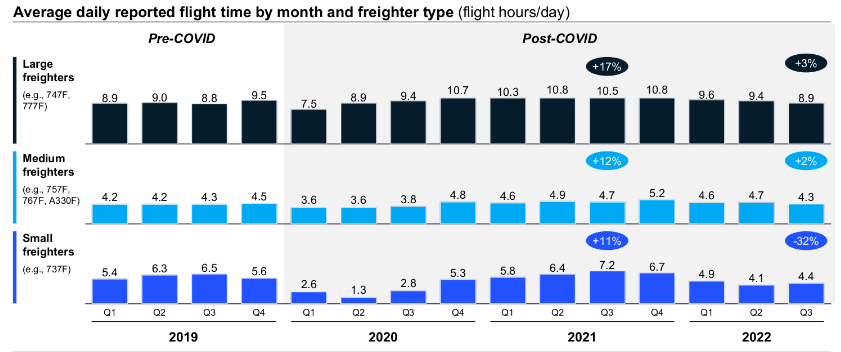

Hausmann said the market downturn is already being reflected in freighters’ daily flight time this year, which is now approaching pre-COVID levels. The average number of operating hours for small freighters like the 737 is now 32% lower than three years ago.

Still, predicting a freighter glut based on historical market cycles is risky because of structural industry changes this decade.

The most obvious change is e-commerce, which has become a dominant force that has changed how airlines and logistics companies operate. Express carriers will fly aircraft within their parcel networks regardless of how full planes are to meet service commitments and outsource more flying to partners because they lack flight rights in many countries.

Massive supply chain disruptions, as well as routine cancellations and delays of passenger flights have convinced many logistics companies that having chartered freighters that they can control is necessary to provide reliable service.

Some airlines downsized during the pandemic and are flying fewer aircraft. The increased range and size of smaller-gauge aircraft, such as the 737 MAX and Airbus A321LR, is giving airlines the option to use them on routes, like the trans-Atlantic, instead of twin-aisle planes, which means less space for cargo.

There are also several new players in the freighter sector. Passenger airlines, such as Air Canada, WestJet and Gol in Brazil, have recently established dedicated divisions to operate cargo jets and augment cargo business that was previously limited to the smaller belly hold of passenger aircraft.

Click here for more FreightWaves/American Shipper stories by Eric Kulisch.

RELATED NEWS:

Will exuberance for air cargo conversions create freighter glut?

Mammoth Freighters adds UK facility for 777 cargo conversions