The annual report by OPEC that reviews and forecasts every corner of the world’s oil producing and consuming sectors should be read with happiness by anybody who needs to buy fuel… including truckers.

OPEC’s World Oil Outlook is one of several 100-plus page reports that are published every year by a variety of leading energy concerns – the International Energy Agency, ExxonMobil and so on. They all seek to lay out the likely scenarios for oil markets over the next few years – the medium-term – or the next 20 years or more. They lean toward conservatism and inevitably miss big sweeping changes like the shale revolution. But that does not mean they do not have value. (We’ve already written about OPEC’s view on IMO 2020 and its positive outlook from the perspective of truckers.)

Reports like this can count what’s out there. The authors who put it together can review the upcoming major oil projects around the world that have been announced and they can do the same with refinery projects. They can also make a reasonable link for the relationship between GDP growth and the concurrent increase in oil demand. Supply shocks can happen because of geopolitics. Demand shocks to the downside can also occur; just think of the collapse in demand that accompanied the financial crisis in 2008 and 2009. Demand shocks to the upside are incredibly rare.

With that in mind, here’s the good news for the industries that rely on oil for transportation:

– There’s plenty of new oil coming on to the market from non-OPEC countries. And while OPEC doesn’t say this, that means its own task to reduce output will become that much more difficult. Total non-OPEC liquids production will rise 9.9 million barrels/day (b/d) between 2018 and 2024, which is just about 10%. (Most estimates put the current size of the global oil market at 100-101 million b/d.) The continued growth in the U.S. shale plays is one reason, but there are significant new supplies coming out of four countries that are all viewed as stable suppliers – Canada, Norway, Brazil and the new oil fields of Guyana in South America.

– Demand, meanwhile, is going to increase 6.1 million b/d by 2024 from the 2018 level. That means demand is going up by that amount in a world where non-OPEC nations are going to be putting another almost 10 million b/d of oil on to the market. This will put tremendous pressure on OPEC to essentially forego any increase in its own output and instead make reductions. That job has been made significantly easier by the fact that so many of its members are facing artificially imposed restraints on their output, whether it’s Venezuela with its long destruction of its once-revered industry, or Iran because of U.S. sanctions. Imagine the task OPEC would have if so many members weren’t in such turmoil.

– Crude oil needs to be turned into products and on that front, OPEC has good news for consumers as well. There’s going to be a lot of new refining capacity built, enough that some of it probably won’t get built or some older, less-efficient plants will need to close. “Potential incremental medium-term crude throughput is estimated at a surplus of almost 4 million b/d relative to the incremental refined product demand by 2024,” the OPEC report said. “While the gap is still moderate in 2019, it widens gradually from 2020 onwards, illustrating a rising surplus of distillation capacity at the global level.”

Some of those closures will come in the U.S. and Canada as other parts of the world see new refinery construction that is more state of the art. “Consequently, the majority of closures are expected for the U.S. & Canada and Europe, with limited closures in other regions,” the report said.

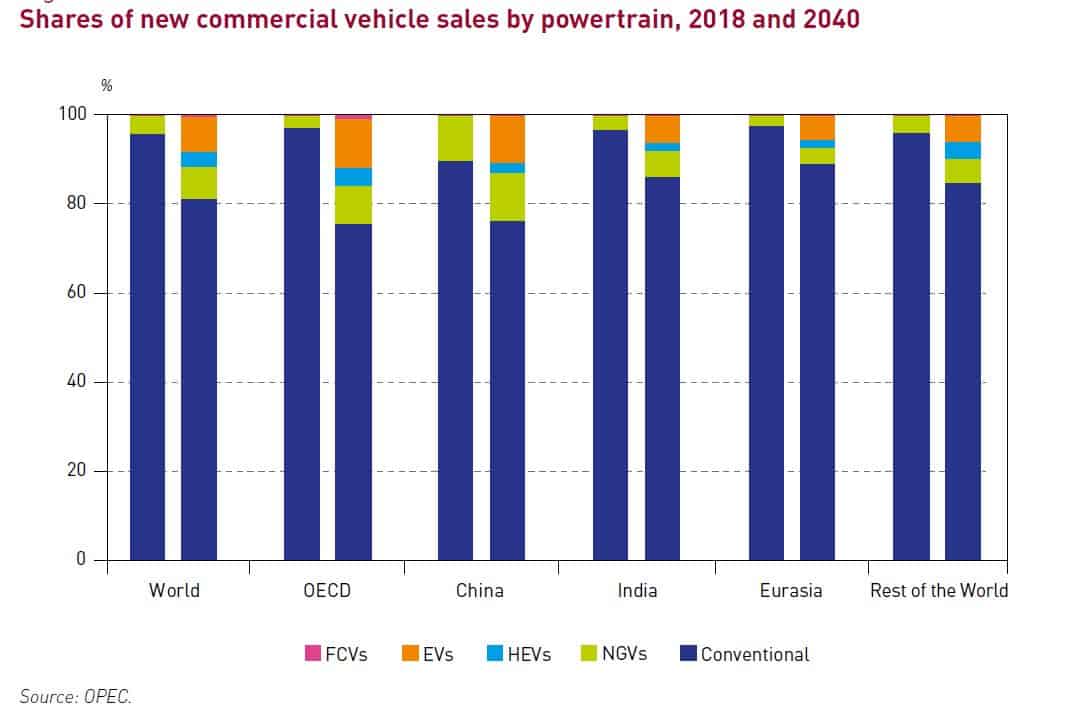

– The OPEC forecast is not high on the prospect for diesel engines being significantly displaced by alternative power sources. “Commercial vehicles remain largely limited to diesel engines,” the report said in looking out at trends until 2040.

“(H)eavy-duty vehicles use primarily diesel engines that tend to be relatively efficient,” the report said in explaining why there won’t be much of a move for trucks to alternative power trains, even as it saw more significant shifts for passenger cars. “Moreover, supporting infrastructure for diesel engines is well developed in most parts of the world.” The report went on to say that there are “limited options” for alternatives to diesel, though the report also referred to the experimental steps that have been taken for battery-powered and hydrogen-powered trucks.

The graph shows the relatively minor shifts predicted by OPEC, with conventional diesel engines mostly holding its share.

– Although the report does not see an end to the oil age, the slowdown it projects in oil use out to 2040 is in line with the idea of a market that is approaching peak demand, with energy needs increasingly supplied by other sources and greater efficiency. From a projection that global demand would be 101 million b/d in 2020, the OPEC forecast sees growth to 105.6 million b/d in 2025 and then tacking on just an additional 5 million b/d out to 2040, when demand is projected to be 110.6 million b/d. That would be an average annual increase of just 500,000 b/d. At present, any growth rate less than 1 million b/d is considered signs of market weakness. And that slow growth will be occurring against a larger global population.