A weekly look at what occurred in the oil markets of the U.S. and the world this past week and what’s ahead.

The size of the increase in price that might be created by the introduction of IMO 2020 is unchanged since January. At least that’s the view of the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA).

The EIA – the forecasting and data arm of the U.S. Department of Energy – came out with a detailed forecast in January of what its economists believed would occur to the price of diesel as the rule requiring tighter sulfur specifications in marine fuels nears its start date in January 2020.

The EIA couldn’t make any predictions prior to that because it didn’t yet have a forecast for what crude prices would be next year. Once that was in place in January 2019, the pencils could be sharpened and the forecasting could begin.

The initial forecast was released in the January Short Term Energy Outlook. The May report was released this past week and it shows almost no change in the EIA’s view.

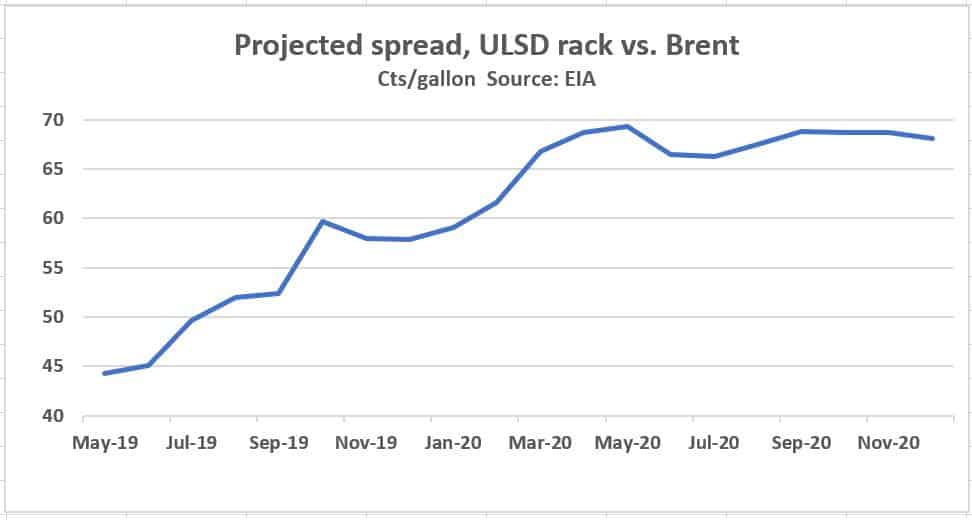

The number that matters as a forecast is to take the EIA forecast of ultra low sulfur diesel (ULSD) wholesale rack prices and subtract the predicted price of Brent from that. (Brent is used as the basis rather than U.S.-produced West Texas Intermediate because the global flows of both ULSD and Brent – the world benchmark – mean that the relationship between those two prices is more indicative of true value than WTI, which faces pipeline constraints in the U.S.)

In January, the predicted spread for that month was about 42.5 cents per gallon (cents/g). It actually came in at about 37.4 cents/g. The forecast for May is 44.3 cents/g.

But from here on in to 2020, the EIA sees that spread rising. The starting point for the forecast is for it to trade in the $70 to $73 per barrel range.

The EIA also has a series of forecasts for the wholesale price of ULSD. But why does the spread between Brent and ULSD matter more than that outright diesel price, since the latter is what is actually getting paid by truckers?

Because the outright diesel price can change radically for reasons that have nothing to do with IMO 2020. A collapse in the economy can send it plummeting; a series of hurricanes rampaging through the Gulf of Mexico can send it soaring. Those sorts of changes in that outright price won’t tell you how ULSD, in the post-IMO 2020 world, is doing relative to the broader price of oil. That’s what matters because if there are structural shifts in diesel prices brought on by IMO 2020, the spread reflects those shifts even as the price goes up and down.

The EIA forecast attempts to do that. In its May report, it has an actual average spread of about 43.9 cents/g between Brent and wholesale diesel for the 12 months through April 2019. By October, it’s up to 55.6 cents/g. In January, the forecast is 57.9 cents/g and peaks out at about 69.2 cents/g in May 2019. By December of next year, it’s 64.5 cents/g.

The report’s numbers are all about 1-2 cents higher than what was released in January, not because the EIA has concluded anything different about IMO 2020 but because it has made small adjustments in some of the benchmark prices needed to get to that forecast spread.

The bottom-line outlook then is still the same as it was in January – the spread between Brent and wholesale diesel is likely to move out about 20-25 cents/g from its current levels. That translates to a gain of about 11.5 percent to 14.5 percent off the base crude price and is ultimately the most important number in the EIA forecast.

What a forecasting agency like EIA does not do is predict spikes. Most economists will look at such a model like this and say it’s a function of broad data and other information. It doesn’t take into account markets that go off the rails during short periods of time. It is a projection of normalcy, not the craziness that can mark short-term market swings.

————————-

With so much focus on IMO 2020, there tends to be a feeling that the only people who are happy about it are environmentalists who are going to see the culmination of their long battle to clean up the sulfur content in marine fuel.

Not so. In a story published this week by OPIS, a news service and price reporting agency, an official of the trade group American Fuel and Petrochemical Manufacturers (AFPM) told a conference in Germany that the switchover is going to be great for refiners.

Geoff Moody, Vice President of Government Relations at AFPM said U.S exports of diesel to Europe will increase to 1.2 million barrels per day (b/d) by the end of 2019. That actually wouldn’t be that big a deal; it’s been more than that level frequently. But he also said they would be 1.8 million b/d by the end of 2020, a figure that has never been reached. The normal range of exports is usually around that 1.2 million b/d level.

Diesel exports out of the U.S. to comply with IMO 2020 are a function of several oil market features. First, the U.S. is a smaller market for marine fuels than such places as the ports of Rotterdam/Amsterdam/Antwerp in The Netherlands or Singapore. Second, the two alternatives to the current supply of high sulfur fuel oil used by ships are marine gasoil – a diesel product – and the new blend known as very low sulfur fuel oil (VLSFO). A distillate intermediate fuel, vacuum gasoil, is blended in with the VLSFO. That’s why there will be a lot of knocking on the U.S. door for its diesel exports.

“Even representatives of European refiners are greeting the coming of the stringent new Marpol Annex VI regulations with considerable enthusiasm,” the article from the International Bunker Conference reported. “‘For them it replaces demand for a low value product, with demand for a high value product,’ said one delegate.”

But the story also expressed the growing concern that a price spike related to IMO 2020 could make the regulation a political target in an election year. “Marginal Northeast U.S. states like Pennsylvania are sensitive to heating oil price rises and will be hard-fought during upcoming presidential campaigning,” the article said. “It might be considered tempting to a presidential candidate to call for exports to be delayed if consumers are eyeing rising bills for keeping warm.”

Heating oil, like diesel, is a distillate and is more similar to it than it was years ago as sulfur rules and other environmental restrictions have aligned in recent years. Its use is regional, focused on the Northeast. But as the article notes, Pennsylvania is in the Northeast and in the upcoming election, it is a big deal.