There is no COVID-era surge in global cargo demand. There’s a lengthy albeit temporary spike in congestion compounded by a localized, stimulus-and-savings-driven demand boom in America.

That explanation for skyrocketing rates gained more traction Friday when liner giant Maersk released details of its quarterly performance.

Maersk — which pre-reported record Q2 2021 results on Monday — estimated that global container shipping demand was up only 2.7% in the second quarter versus the same period two years ago, prior to the pandemic.

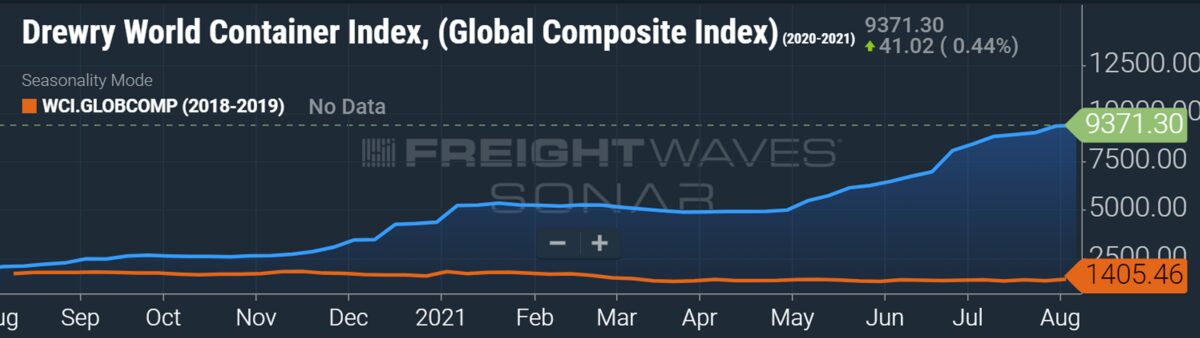

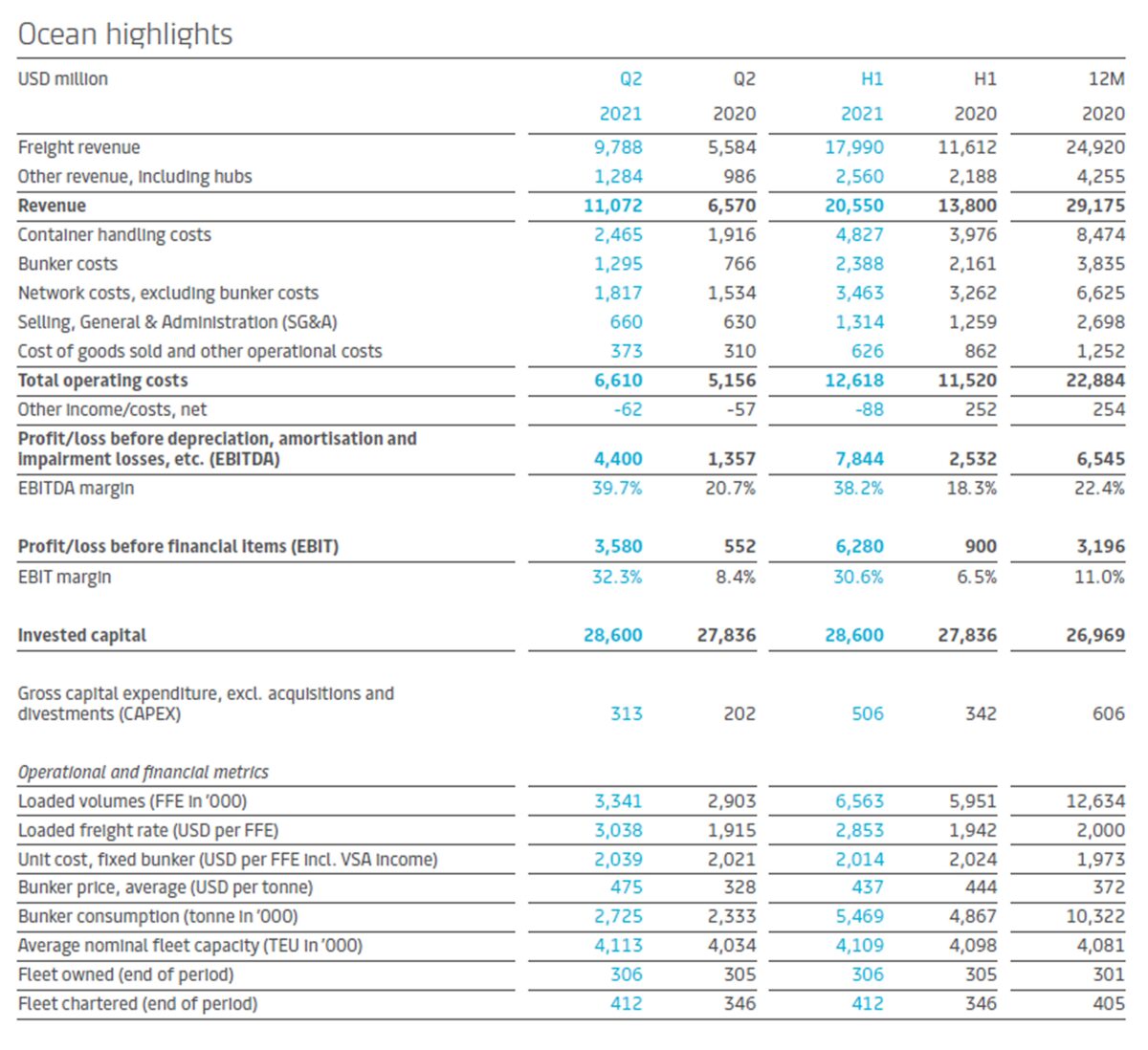

And yet, Maersk’s average freight rate (including both contract and spot business) was $3,038 per forty-foot equivalent unit, up 63% from $1,868 per FEU in Q2 2019. The Drewry World Container Index of spot rates rose to $9,371 per FEU this week, 6.7 times what it was two years ago.

Consultant Lars Jensen, CEO of Vespucci Maritime, told American Shipper, “Global demand for the first part of the year is up around 4% compared to 2019. We did not have a capacity problem in 2019. We had enough ships, we had enough containers, ports were fine, and trucks and rail were fine, at least from a global perspective.

“With 4% global demand growth since then, we should not have a problem now. You have some skewing because of the demand boom in North America, but none of this is down to a global demand boom — because that doesn’t exist. The problem right now is predominantly one of capacity.”

Congestion curbs effective capacity

Ocean freight capacity is being heavily curtailed by congestion, with equipment tied up both on land and at sea.

Maersk sent out a customer advisory on Wednesday titled, “Critical help needed — congestion increasing.” The advisory pleaded with U.S. customers to return equipment more quickly, stating: “We do not anticipate the congestion decreasing any time soon. On the contrary, the industry overall is forecasting higher [U.S.] volumes into early 2022 and beyond.”

Alphaliner reported this week: “Carriers need much more tonnage as ships get stuck in congested ports in both the U.S. and Asia. Some carriers reported that they needed at least 20-25% more fleet capacity [in the trans-Pacific] to continue carrying the same amount of cargo.”

Maersk confirmed that its own effective fleet capacity was down versus pre-pandemic due to congestion.

Vincent Clerc, executive vice president of Maersk, said on Friday’s conference call: “Our fleet has grown by 2% from 2019 but our volumes are down by 3%. It basically takes more TEUs [twenty-foot units of fleet capacity] to transport each FFE [forty-foot boxload of cargo]. That will go away when congestion goes away.”

Evolution of the rate spike

“The U.S. is booming enormously,” explained Jensen. “And while you can certainly shift vessels and containers from one trade to another, you cannot shift ports from one trade to another. It also doesn’t do you any good to have plenty of trucks in another country if the trucks are needed in the U.S. The same with rail.”

On the capacity side of the equation, congestion drivers have just kept on coming — “one domino after the other” — from the anchorage situation off California to the Suez Canal blockage to the closure of the port in Yantian, China. The next threat on the horizon is the delta variant outbreak in China.

“On top of that, you’ve had every conceivable little operational mishap,” Jensen continued.

“You always have some vessel breaking down somewhere. Normally if that happens, you charter a replacement vessel or shift the cargo to another service. But now, there are no vessels left to charter and shifting the cargo to another service is out of the question. They’re already all booked. So, every tiny operational mishap adds more cargo to the pile of cargo you can’t move. And things are just getting worse.”

‘Everything we see now is temporary’

When congestion does eventually clear, which appears more likely to be a 2022 event, spot rates could pull back quickly from ultra-high levels if more effective capacity is injected amid unexceptional global demand growth.

“We need to bear in mind, given the extreme levels that we see on the short-term rates, that the correction towards a more normal level could be quite rapid,” said Clerc.

Jensen said, “I believe everything we see now is temporary. It’s all governed by COVID and eventually it’s going to go away. I don’t see COVID changing anything structurally. So, for me, what’s interesting is the underlying trajectory of the industry prior to the pandemic.”

That trajectory, he said, had been one of gradually improving fundamentals for carriers, better capacity management due to carrier consolidation, and stronger rates.

After congestion eases and capacity returns to the market, Jensen predicts that “freight rates will come down substantially from where they are today, but they’re not going back to anywhere near where they were pre-pandemic. They will definitely tumble compared to where they are now, but it will still represent a sizable increase compared to where they came from.”

Click for more articles by Greg Miller

Related articles:

- Beware ‘nasty side effects’ if government targets ocean carriers

- US ports face peak-season ‘gridlock plus’ as anchorages fill

- Container lines are poised to hit $100 billion profit jackpot

- Why stratospheric container rates could rocket even higher

- Inside container shipping’s COVID-era money-printing machine

Maersk Q2 2021 key performance indicators:

fred caiger

The ridiculous 8ncrease in shippi g costs are going to severely damage the competitiveness of businesses who rely on importing their stock. It will also act as a barier for startups entering markets. There seems to be no substantive financial reason for this” get rich quick increase”. I hope this greedy action backfires on the shipping companies.

John Doe

Excellent article by Greg Miller

Amos Emmanuel

Any ways, what ever happens these days, it will be concluded it is caused by covid… but the truth is, all of these things are formed and concluded. covid is already here, and might not disappear all of a sudden.

Muhammad

BBC Cargo Services from UAE-based Company have own warehouse for Cargo Packing loading unloading Containers.

In our Services, we are offering by SEA, by AIR, and by Land Shipping. Containers Shipping and Clearance services available :

Visit Us: http://www.bbccargo.ae

Contact Us: +97142831100

J+Boh

Most of those products have also been sitting on the water for 6 or 10 months fyi. They are making money hand over fist because these were ordered a YEAR AGO in many cases. And they know you’ll pay to get it.