This article brought to you courtesy of NEXT Trucking

The port of Houston is one of the fastest growing U.S. container ports, thanks in large part to increasing exports of petrochemicals from the region. Its challenge will be keeping the import side growing, and boosting Houston’s ability to handle larger vessels.

Through July 2019, loaded imports into Houston are up 8.4% from the year earlier period to 715,849 twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs).

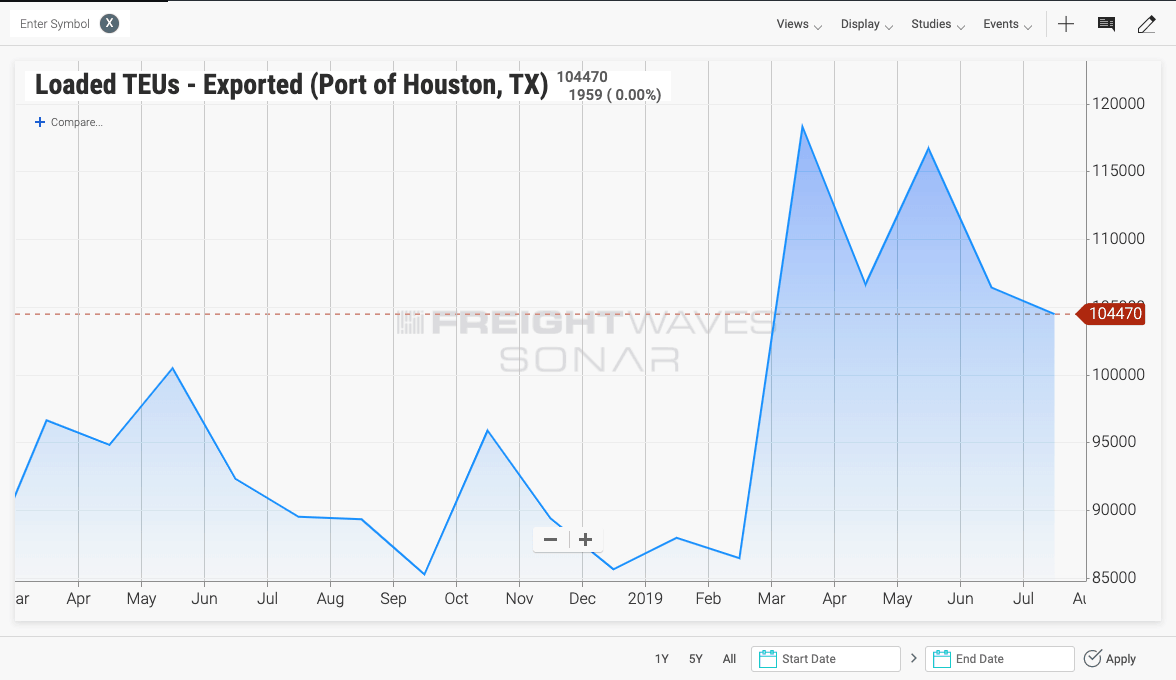

Exports are growing at an even faster rate with 726,962 TEUs of exports through July, a 15% rise from the same period in 2018. The growth rate has been accelerating over the past year.

Exports are being fueled by the growth in Gulf Coast manufacturing of pelletized resins, the raw material for finished plastics goods. Last year, resin accounted for 30% of exports.

“There’s been a real push earlier this year for resin exports,” said Patrick Maher, executive vice president at Houston-based, intermodal drayage provider Gulf Winds International. “We’ve started to see incremental growth each month and it just kind of builds. The flow gets a little bigger each and every month.”

The Baytown region in Houston, located across the Houston Ship Channel from the major container terminals, is home to many of the packagers that stuff resin into containers for export. Belgium’s Katoen Natie set up a 2 million square foot resin packaging facility. DHL Supply Chain, through its acquisition of Exel, and Houston’s Packwell are also major local packagers.

With most of the resin distribution within 20 miles of the port, drayage drivers are regularly making two to three turns per day. Maher said Houston’s container terminals are highly efficient and offer low turn times.

“There is a tremendous amount of warehousing growth in Baytown, all related to resin,” Maher said, adding that additional resin manufacturers are slated to open in 2021 and 2022.

“We’ve had that first wave of resin exports that hit us, but there are still many plants that will come online in the next two to three years,” Maher said. “There will be tremendous growth in packaging, warehousing and trucking.”

One risk to that growth will be the degree to which shippers send volumes to other Gulf Coast and Southeast ports. Maher said shippers are likely to do so to mitigate overall supply chain risk such as a closure as happened during Hurricane Harvey or if local rail or transportation capacity bottlenecks develop.

Houston also needs to keep import volumes, a mix of retail and industrial goods, growing as well. While the regional economy is doing well, retail distribution centers are not being added as quickly as in Savannah and Ontario, California. Warehouse space availability “cause[s] real issues across the supply chain,” said Lidia Yan, Chief Executive Officer of drayage NEXT Trucking. “This is particularly true as shippers are forced to confront uncertainty due to the trade wars.”

But Port Houston is looking to bring in more import volumes by marketing itself as an all-water alternative for Asia’s retail goods exporters to reach U.S. Midwest markets.

Retail goods coming into the Southern California gateway face a two-week ocean voyage, plus another five to seven days via rail to the Dallas distribution hub.

An all-water move to Port Houston plus the 240-mile truck trip to Dallas might only take a few days longer now, Maher said. Costs and transit times are becoming much more even to Houston versus the West Coast, giving shippers additional import strategies, Maher said.

Keeping imports in balance with exports is key to keeping Houston’s container volumes growing. The fact that ocean carriers do not have to reposition containers and can keep vessels full on both inbound and outbound trips allows them to keep ocean shipping rates economical and add new origin and destination ports for services.

“We are optimistic that the port will continue to execute its import growth strategy, keeping imports versus exports in balance, especially as additional ocean services are added into the Gulf,” Maher said.

Another hurdle for future growth is the port’s physical limits. Barbours Cut, the smaller of Port Houston’s two container terminals, added taller post-panamax ship cranes and more container yard space to bring its throughput up to 2 million TEUs annually. But the waterside is only dredged to 45 feet, while the largest container ships require depths of 53 feet.

Most ships coming into Houston are in the 5,000 to 6,000 TEU range, with the largest vessels calling on the port having 8,000 TEU capacity. But ships of 10,000-TEU size or higher are regularly calling at other ports.

Earlier this year, Texas passed a law that allows Houston’s pilots to require one-way traffic on the Houston Ship Channel when they pilot large vessels, typically over 1,100 feet in length due to safety concerns. The restriction effectively limits vessel calls of larger container ships.

But Houston is looking to accommodate larger ships. The Port of Houston Authority is working with the Army Corps of Engineers on a channel improvement project that will widen the Houston Ship Channel from 530 feet to 700 feet to enable two-way traffic. The project will also widen the Bayport and Barbours Cut container terminals to 455 feet so as to handle ships up to 14,000-TEU.

The roughly $1 billion channel improvement project is expected to start in 2021.