Competition for air cargo business in the Greater Chicago area is heating up with Milwaukee’s main airport planning to build a large terminal for freighter aircraft and poach traffic from Chicago O’Hare, the dominant cargo hub in the region, and rising upstart Chicago Rockford airport.

The local economy’s strength suggests the investment has merits, but capturing more than surplus shipments from a major international gateway like O’Hare will be a tall order, according to an expert.

Project organizers say they are confident they can attract cargo airlines and logistics companies interested in fast access to the Chicago megamarket at far less expense than at O’Hare, and without the chronic congestion, as well as tapping the rapidly growing industrial base in southeast Wisconsin.

Crow Holdings, a privately held real estate investment and development firm with $24 billion of airport assets under management, announced this month it will develop and operate a 288,000-square-foot logistics hub at Milwaukee Mitchell International Airport (MKE) in exchange for a multidecade ground lease.

The Milwaukee airport is a 70-minute drive north from O’Hare.

“There’s the built-in demand for the businesses in Milwaukee, but also a lot of businesses are going to find it cheaper to fly it into Milwaukee and truck it down to Chicago versus paying this premium of flying it directly into Chicago,” said Jack Rabenn, vice president – industrial at Crow. “We feel very comfortable with our marketing assumptions.”

The building won’t be delivered until the back half of next year — at the earliest. By then, the down air logistics market should be on the upswing again, Rabben added.

The Milwaukee County government opted to transfer operating rights for a large piece of property on the south side of the airport, which until 2010 was home to a U.S. Air Force Reserve base, to a concessionaire after struggling to find tenants on its own.

The MKE airside flow center will have high ceilings and a wide footprint to facilitate storage and sorting, as well as 74 docks and 99 trailer stalls, according to project organizers. Those characteristics stand in contrast to cramped facilities at many airports, including O’Hare, that were built decades before the current generation of large freighter aircraft and are subject to frequent backlogs. (The city of Chicago has recently added some modern cargo warehouses but still has older properties.)

A ramp addition will enable five 747-size freighters, eight standard jets — or some combination — to park in front of the cargo center. The building will be constructed with energy-efficient precast walls and customized to meet the requirements of potential tenants.

Rabenn said the range of candidates that could establish operations at Milwaukee airport include integrated express carriers, all-cargo airlines and logistics companies with their own chartered fleets.

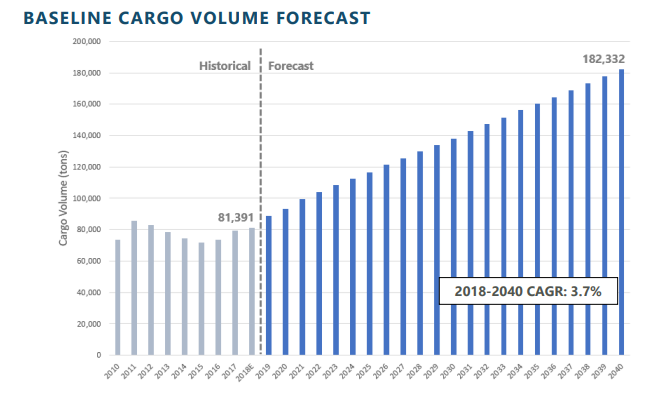

A study conducted for the airport authority forecasts 3.7% annual compound growth to reach 182 million tons in 2040, more than double the volume of any year in the preceding decade. Boeing’s 20-year outlook calls for a 4.1% global growth rate. That may not seem big, but it quickly adds up. And businesses have started leaning more toward relying on freighters over passenger belly capacity to ensure greater control of time-sensitive shipments. The Milwaukee airport master plan says the growth in e-commerce volumes will drive increased use of dedicated cargo jets at MKE.

FedEx (NYSE: FDX), UPS and DHL already operate at Milwaukee airport. FedEx leases 86,000 square feet in a legacy cargo building and makes deliveries with a range of medium and large freighters. Last year it conducted nearly 1,100 round-trip turns at MKE. DHL operates a daily Boeing 737 freighter from Cincinnati that primarily transports packages for Amazon deliveries in the region and uses a third-party cargo handler.

UPS (NYSE: UPS) is the most likely to be interested in a new facility. It only occupies 18,000 square feet, split in two separate areas, with 11 truck bays. Its flight activity is a quarter of FedEx’s. The company has indicated it has an urgent need for restroom facilities, office space, a container sorting facility and other equipment. It wants one contiguous location so employees don’t have to waste time traveling between the two work spaces, according to the updated master plan in September.

Ramp space for UPS aircraft is also at capacity when the daily MD-11 jet and Beechcraft 99 regional feeder aircraft operated by Freight Runners Express occupy the apron at the same time. Overflow feeder aircraft are sometimes parked on the deicing ramp when not in use. UPS says it has parking capacity for eight small aircraft and needs four more spaces. Another problem is the building’s existing design for smaller trucks makes maneuvering tight for 53-foot trailers in use today.

UPS is considering expanding at other regional airports to accommodate future demand unless MKE can be quickly improved, particularly through consolidation and technological improvements, the master plan said.

The report says existing cargo areas for multiple users are either underutilized with low efficiency or over capacity.

Market opportunities

Southeast Wisconsin, with a huge concentration of million-square foot industrial facilities, is prime territory for dedicated cargo service. Amazon and Uline — a large distributor of shipping, packaging and industrial supplies headquartered in Pleasant Prairie, Wisconsin — have a large presence, along with other big box warehouses. And many new industrial buildings have been built during the past five years in Milwaukee to replace older Class B and C properties. Milwaukee airport also can support demand out of Madison and Green Bay.

Meanwhile, smaller warehouses and truck terminals dot the landscape near the airport itself.

Milwaukee’s built-in industrial infrastructure gives it an advantage over Chicago Rockford International Airport, said Rabenn.

“Milwaukee is a bona fide city with a large metro area and lots of surrounding industrial properties,” he said. “In Rockford there’s not much complementary industrial space around it.”

The airport sits along Interstate Highway 94, connecting it to downtown Milwaukee, as well as south to Chicago.

Rockford has experienced rapid growth in the past five years. It is now UPS’ second-largest U.S. air hub and a major node in Amazon’s private air network. It also has attracted freight forwarders Maersk Air Cargo and DB Schenker to lease airside space.

Dallas-based Crow Holdings and CBRE (NYSE: CBRE), the giant commercial real estate services firm marketing the redevelopment, are touting Milwaukee airport as a legitimate option for tenants looking to avoid congestion and high costs associated with basing operations out of O’Hare.

Chicago O’Hare International Airport is one of the biggest U.S. airfreight gateways for cargo, prized for its central location and size, access to extensive ground transportation and logistics infrastructure, and proximity to manufacturing centers.

But cargo bottlenecks are common at O’Hare during peak shipping periods because many terminals are outdated, lack modern technology, have limited truck access and haven’t adopted electronic appointment systems. It can often take days for commingled shipments to be sorted and made available for pickup, while truckers report wait times of several hours. Shipper frustration became more acute during the pandemic as a spike in freighter activity swamped facilities.

“The idea here is not only can we solve the congestion issue, but it’s substantially less to operate out of Milwaukee if they [logistics companies] don’t need to be directly at O’Hare. We can offer that benefit at a huge operational cost savings,” said Rabenn, pointing to landing fees that are half as much, lower taxes and a substantially lower ground lease that enables Crow to charge tenants lower rent.

“So we think our value proposition is quite strong when it comes to attracting tenants to the region.”

Rabenn said Crowe also has an undisclosed equity partner that will provide extra financing and make it easier to attract debt financing as needed.

Michael Webber, who provides cargo consulting services to airport operators and civil aviation authorities, agreed that Milwaukee is a strong market with manufacturers and distributors like Harley-Davidson but that the airport needs to modernize its facilities.

“The business case is largely based on replacing older capacity in Milwaukee, plus meeting a really robust metro economy around Milwaukee,” Webber said. “That’s the foundation of this.”

But Webber questioned how much cargo could be pulled from O’Hare, which is a magnet for widebody passenger traffic in the region.

“I think they’re in a position to certainly pick up overflow from that Chicago market,” but O’Hare has an overwhelming advantage as an international gateway with a mix of cargo carried by passenger aircraft and freighters, Webber explained. Freight forwarders like using airports with a wide range of traffic from around the world because it gives them more shipping options and the ability to create specialized routes for their customers when direct flights aren’t available.

Secondary airports typically secure freighter services when a logistics company has a key client, or two, with enough volume to justify chartering dedicated flights to locations where they can enjoy priority treatment, said Webber, who has also studied the cargo market for the MKE airport authority.

(Correction: Jack Rabben’s name was misspelled in an earlier version of this story.)

Click here for more FreightWaves and American Shipper articles by Eric Kulisch.