The historic surge in U.S. crude production has reverberated across domestic and international freight systems, affecting every transport mode.

Maritime headlines have spotlighted the global tanker sector, which has been buoyed by sharply higher U.S. exports of crude and refined products.

But there is another segment of maritime that’s heavily exposed to the U.S. petroleum industry and deserves more attention – the U.S. inland tank barge industry.

The revolution in U.S. crude production initially led to a period of overbuilding and depressed rates for tank barges. Rates are now on the upswing as capacity has been pared and the volume of crude oil and petroleum products shipped via the Mississippi River and its tributaries is escalating.

Today, America’s heartland river system is dotted with an increasing number of tank barges full of petroleum, slowly meandering their way to their destinations.

Tank barge demand is growing

The U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) compiles monthly data on volumes of crude and petroleum products crossing between Petroleum Administration for Defense Districts (PADDs). There are five PADDs covering the states of the East Coast, Gulf Coast, Midwest, Rockies and West Coast.

Estimates using aggregated EIA data offer an approximation of inland tank barge trends, but don’t necessarily reflect actual demand, for two reasons. First, the EIA only tracks volumes moving between PADDs and does not capture volumes shipped within PADDs. Second, true vessel demand is not measured in volume; it’s measured in ‘ton-miles,’ or volume times distance.

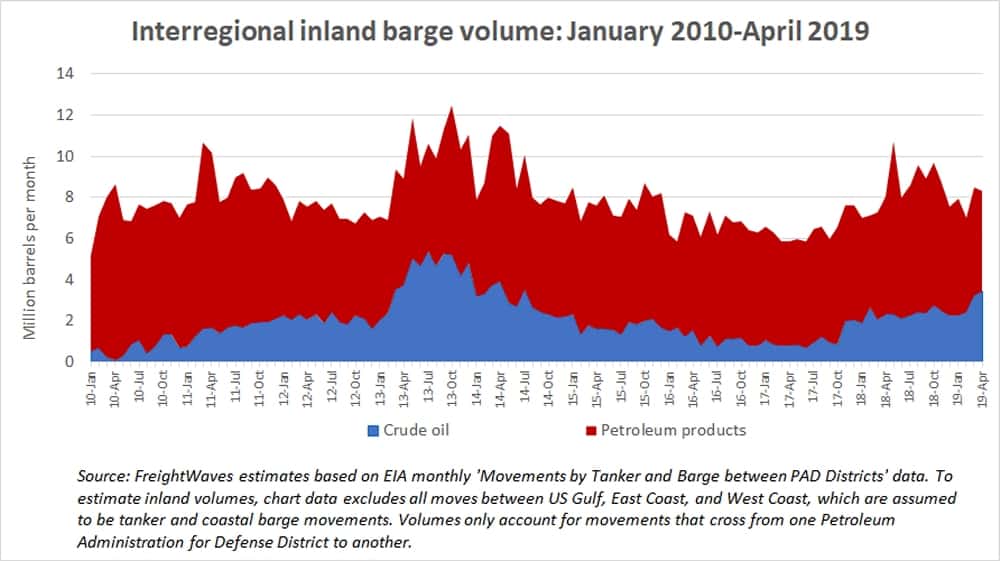

Aggregated EIA data confirms that the petroleum products trade is a much larger market for inland tank barges than crude oil, although the mix has varied. Between January 2010 and April 2019 (the last month EIA data is available), products accounted on average for 75 percent of volumes between PADDs.

Crude oil briefly comprised 50 percent of inter-PADD river volumes in the second half of 2013, then slumped back to just 15 percent in the first half of 2017. This year, crude oil’s share is rising again, to around 40 percent of total inter-PADD liquid volumes in March and April.

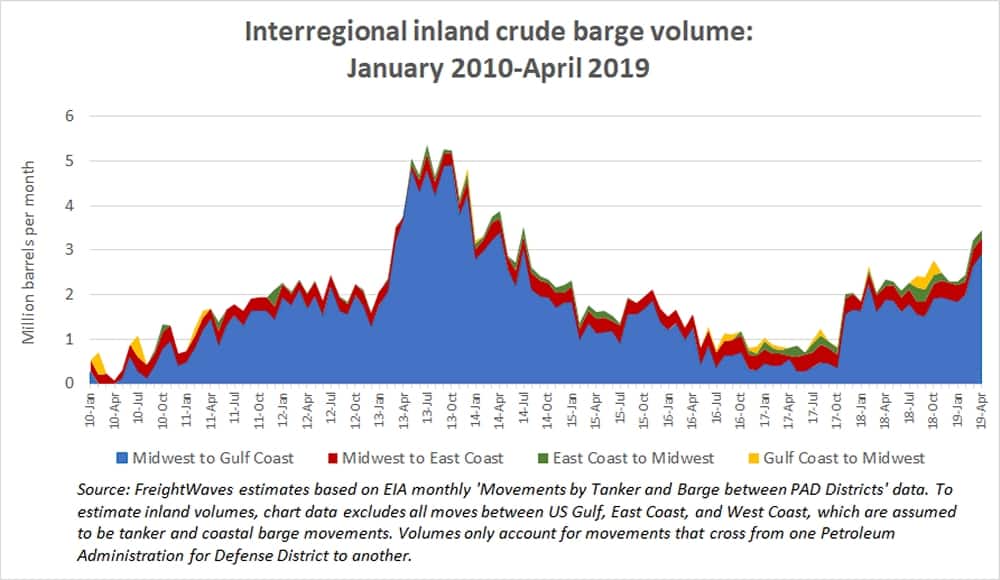

The vast majority of crude oil volumes – 80 percent – are coming south from the Midwest into the Gulf Coast states, either via the Mississippi River or the Arkansas River. Smaller volumes are moving between East Coast states and the Midwest via the Ohio River, and from Gulf Coast states to the Midwest.

Crude oil volumes on U.S. rivers surged in 2013, slid through the next three years – coinciding with the plunge in crude pricing in 2014-15 – and rebounded in 2018-19. Cross-PADD inland river crude volumes in the 12 months through April 2019 were up 64 percent over the prior 12 months.

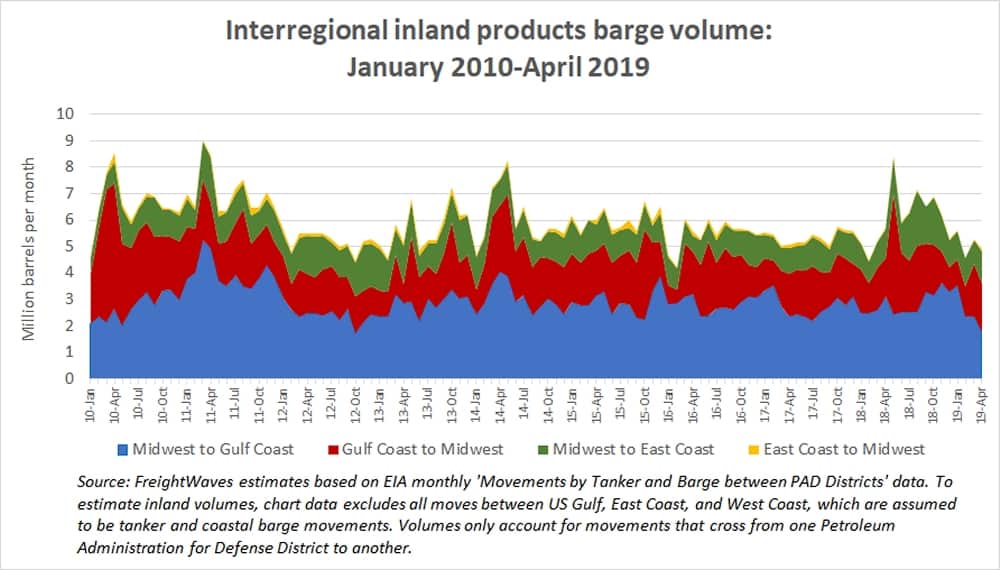

On the more important products side of the equation, 49 percent of volumes since 2010 flowed south from the Midwest to Gulf Coast states, 31 percent in the opposite direction, 18 percent from the Midwest to the East Coast (via the Ohio River), and 2 percent from the East Coast to Midwest states. Inter-PADD products volumes in the 12 months ending in April were up 15 percent compared to the prior year.

Kirby Corp (NYSE: KEX), by far the largest player in the inland tank barge sector, is particularly bullish on petrochemical cargoes, pointing to $140 billion in investments for new petrochemical projects under development.

Kirby announced second-quarter results on July 25. During the conference call with analysts, Kirby chief executive officer David Grzebinski affirmed, “The good news in my mind is that the demand side is solid. Our customers have invested billions in new plants and new facilities and expansions.

“They’re getting low-price natural gas that helps run their plants and converts into some of the petrochemicals. Clearly, the light crude coming out of the shale is also a good feedstock source. So, when you look at the demand side of the barge picture, it’s pretty robust, and it should be good for a while.”

The downside demand risk to the U.S. tank barge sector stems from the broader risks to the U.S. energy complex.

Just as with ocean-going tankers, inland tank barges are negatively affected by slower U.S. crude production growth – as was clearly seen in 2014-15. Concerns have recently been raised about the potential for slowing growth in U.S. crude production, as well as for slowing global demand for petroleum.

Vessel capacity flat, rates rising

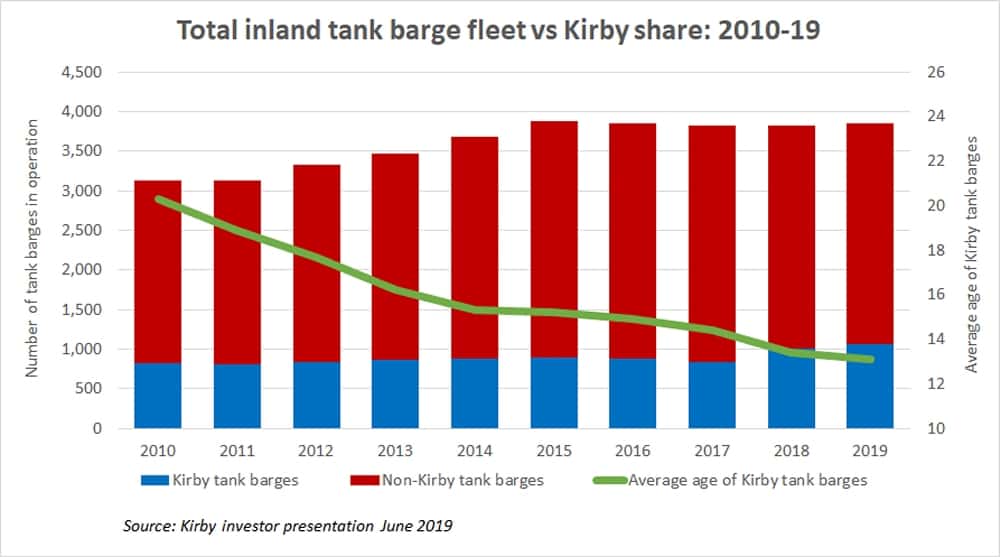

Kirby estimates that there are currently 3,858 tank barges in service. In 2009-11, the number of tank barges plying U.S. rivers was steady at 3,125. The numbers started ascending in 2012 as speculative investors reacted to rising crude volumes on the rivers. By 2015, there were 3,875 tank barges in service, up 24 percent from 2011.

Excess capacity in relation to demand spurred a rate downturn in 2014-2018. Capacity pulled back slightly to 3,817 tank barges in 2018, according to Kirby’s estimates, off 2 percent from the 2015 peak.

Capacity is almost flat year-to-date in 2019 (up 1 percent). The question ahead is whether newbuilding investments will start ramping up annual capacity growth.

Newbuilding orders are driven by two different rationales: replacement of older tonnage to reduce maintenance costs from older ships and incremental growth to increase exposure to rising freight rates. It’s the second rationale that can cause problems for vessel interests, if it leads to too much new capacity.

Kirby reported that inland spot rates were up 15 percent in the second quarter year-on-year and up 20-25 percent from the down-cycle trough, with term rates (on contracts of a year or more) up in the mid- to high-single-digits versus expiring contracts.

Grzebinski addressed the newbuilding concern on the quarterly call. “The cost of new barges is up,” he explained, pointing to higher steel prices. The cost of operating barges is also up, he added, citing higher labor costs and the cost of complying with new towing safety regulations.

Grzebinski maintained that rates are improving but they need “to get even higher to justify newbuilds. At current [freight] prices, you can’t get enough return on capital. It needs to move probably another 20 to 30 percent higher to justify a return on capital on new equipment.”

He acknowledged that 175 to 200 new tank barges are expected to be delivered by the end of this year and into early 2020, but he said that “the majority, well over 100 of those, are for replacement, not really new incremental growth.”

He continued, “We’ve been in a downturn for four years and we’re just starting to see positive cash flow and many of our competitors need some replacement equipment. With replacement [orders], they kind of have to do it. They were working the equipment and they’ve got stuff retiring.”

He added, “When you start looking out to late 2020 and into 2021, the order book is pretty minimal, and that’s because pricing still needs to go higher to justify incremental new capital for growth.”

Kirby’s advantages of scale

When analyzing the inland tank barge sector in terms of market share, consolidation and merger and acquisition (M&A) activity, it’s all about Kirby.

The company has 1,067 inland tank barges in service, representing 28 percent of the total fleet, dwarfing the market shares of its competitors, including American Commercial Lines (11 percent), Canal Barge Company (8 percent), Ingram Barge Company (7 percent), and Hardin St. Marine (7 percent).

Kirby’s much higher fleet size gives it three main advantages versus rivals. First, it enjoys at least some pricing power with suppliers.

Second, a larger fleet size allows it to cater to multiple types of liquid bulk while minimizing tank cleanings. Companies with small fleets that carry various cargoes need to clean tanks when switching from one commodity to the next. Kirby has so many tank barges on the water that it can dedicate various units to specific cargo types.

Third, Kirby’s scale allows it to provide a long-term contract option called a contract of affreightment (COA). Unlike a vessel time charter, which provides a shipper with the use of a specific vessel for a certain period, a COA stipulates that a specified volume will be moved over a certain period, with no vessels specified.

A ship owner with a small number of vessels cannot offer COAs, because it cannot guarantee it will have enough ships in the right place to service the shipper’s needs. For example, in the liquefied natural gas (LNG) sector, companies do not have large enough fleets to provide COAs, so they coordinated their ships via a common pooling arrangement called the ‘Cool Pool’ to do so.

In the inland tank barge sector, Kirby is so large that it can provide its own COAs. Of its current term business for periods of a year or more, 63 percent of revenues derive from time charters, 37 percent from COAs.

Capital access and consolidation

Kirby’s fleet is now so expansive and its capital access is so much better than competitors’ that the idea of anyone catching up to it is virtually inconceivable. The more realistic question is how much bigger does Kirby want to be?

Kirby, which also has interests in coastal barge and engine services businesses, has a current market capitalization (shares outstanding multiplied by the share price) of $4.6 billion. There is no other U.S.-listed shipping company that has a market cap even close to that.

The second-highest is Seaspan Corp (NYSE: SSW), with a market cap of $2.2 billion, less than half of Kirby’s despite the fact that Seaspan owns 112 container ships with a total capacity of over 900,000 twenty-foot-equivalent units (TEU). The largest U.S.-listed tanker company, Euronav (NYSE: EURN), has a market cap of $1.95 billion, well below Kirby’s, despite Euronav’s ownership of 68 tankers with aggregate capacity of 16.6 million deadweight tons (DWT).

Kirby is equally impressive on the debt front. It has an investment-grade credit rating from Moody’s of Baa3. Investment-grade ratings are almost unheard of in maritime circles due to cyclical volatility. AP Moller-Maersk, owner of Maersk Line, the largest liner company in the world, has the same credit rating as Kirby.

Kirby’s stock strength and credit rating provide it with the capital access to acquire other tank barge companies. Most of its growth in recent years has been through M&A activity.

It has spent over $900 million on fleet deals and vessel acquisitions since 2015, including $244 million for the 63 tank barges of Cenac Marine in March and $422 million for the 163 barges of Higman Marine in 2018.

Kirby’s takeovers are partially about incremental growth to increase operating leverage (i.e., exposure to freight rates), with the number of tank barges in its fleet up 26 percent from 2016 levels. But its M&A activity is also about replacement, which reduces average age and maintenance costs. Since 2008, the average age of Kirby’s fleet has dropped from 23.9 years to 13.1 years.

Will Kirby’s M&A push continue, pulling its market share ever higher?

Some analysts believe Kirby will opt to keep its market share at around 30 percent, because at higher concentrations, ship owners’ fleets tend to compete with themselves for the same cargoes and diseconomies of scale start to outweigh economies of scale.

A look at Kirby’s historical fleet share lends credence to this theory. Although the company’s current fleet share of 28 percent is well above its 23 percent share in 2016, it’s still under the 31-32 percent shares Kirby held back in 2002-08. In the years since 2000, its fleet has been an average of 27.4 percent of the total fleet size.

The other reason to question Kirby’s appetite for future M&A deals involves strengthening rates. Kirby has a well-known reputation for buying fleets at low points in the market, allowing it to obtain youthful capacity at prices at a discount to replacement cost (i.e., the cost to order newbuildings). If freight rates improve – as they are doing now – M&A deals may not be discounted enough to entice Kirby.

Apparently, market pricing has not yet risen enough to quell Kirby’s takeover interest. On the quarterly call, an analyst asked Grzebinski about “at least one” of Kirby’s largest competitors that are “still under a lot of pressure financially” and whether Kirby is interested in more acquisitions.

“The short answer is yes,” affirmed Grzebinski. “We like inland assets. We’re always looking. We’re always interested.” More FreightWaves/American Shipper articles by Greg Miller