A widely held theory on pandemic spending is that container imports surged because Americans bought a lot more goods when COVID prevented them from buying services. Ergo, with more vaccinations and fewer hospitalizations, Americans will resume spending on services and consequently have less to spend on goods, the pandemic-induced driver of import demand will wane, spot rates will fall, and the market will return to some semblance of normality.

And yet, Americans’ spending on restaurants, air travel and other services has rekindled but there’s still no evidence of a drop in spending on goods.

Container imports remain at peak volumes. Spot ocean rates are still rising. Inventory-to-sales ratios remain stubbornly low — so low that it now looks inconceivable that they can revert to normal this year.

Paul Bingham, director of transportation consulting at IHS Markit (NYSE: INFO), told American Shipper, “We’re too far into the year without having recovered [inventories] to get out of this in 2021. We have to look to 2022 for any hope. So many portions of the supply chain are so far behind that it’s not going to happen in the next six months.”

Consumers spend more on services

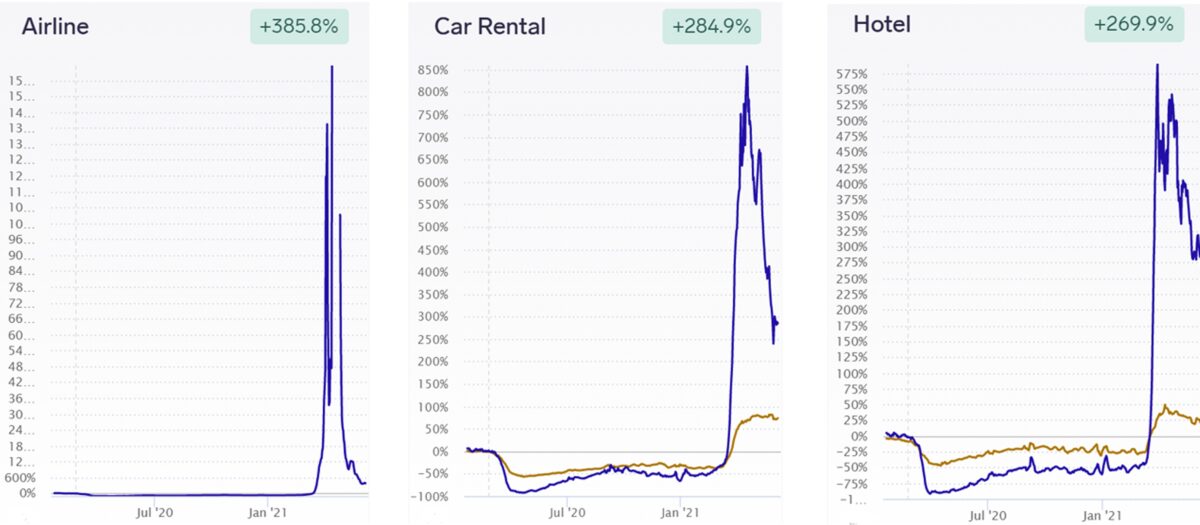

Real-time credit card usage is tracked by 1010Data on a platform powered by Exabel. This data shows a year-on-year (y/y) rebound in domestic travel spending since late March, with particularly high y/y numbers in April (given that last year’s April spending was depressed by lockdowns). As of Monday, this dataset showed that spending on airlines, car rentals and hotels was up 356%, 285% and 270% y/y, respectively.

1010Data shows a similar rebound in restaurant spending, also since late March, with y/y gains peaking in April.

As of Monday, spending on casual dining, fast casual and fine dining was up 76%, 30% and 308% y/y, respectively

Inventory-to-sales ratio historically low

This notably higher spending on services has yet to dent spending on goods, and consequently, containerized import demand.

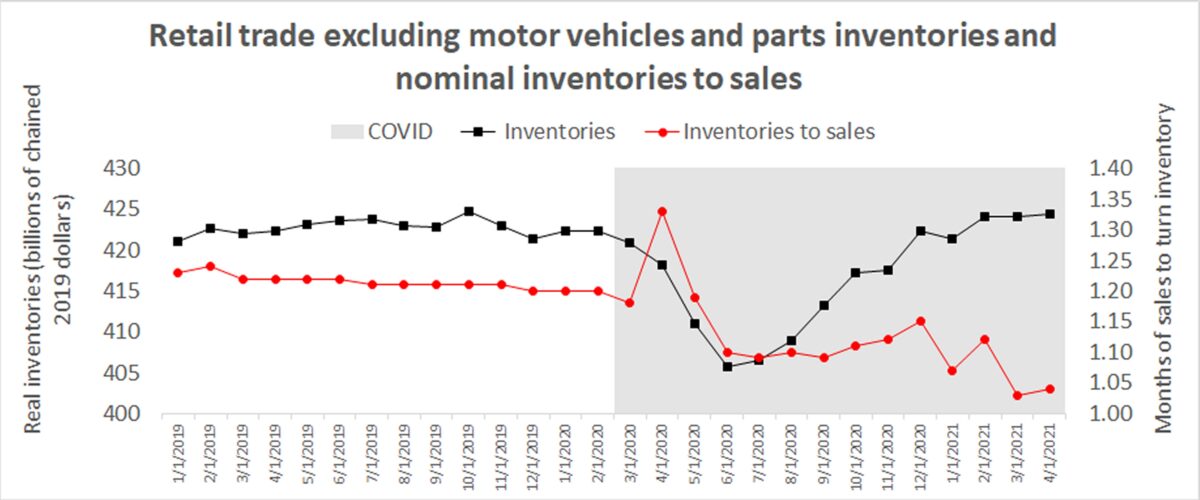

Jason Miller, associate professor of supply chain management at Michigan State University’s Eli Broad College of Business, plotted retail inventory-to-sales levels through the end of April excluding vehicles and automotive parts (these categories excessively skew the numbers in relation to containerized goods). This dataset shows that real inventories have rebounded to pre-COVID levels, but the inventory-to-sales ratio remains historically low.

As of the end of April — a month when credit card data showed much higher spending on services — retail inventories were still just 1.04 months of sales. That’s the second-lowest level ever, just a single basis point above the all-time nadir of 1.03 months in March.

According to Miller, “Given current capacity constraints, especially with COVID-19 outbreaks affecting Chinese exports, I cannot see a scenario where retailers are able to build inventory-to-sales to pre-COVID levels by October and November [for the holidays].”

Making the restocking outlook even more challenging: Non-seasonally adjusted retail sales ex-vehicles and parts in May was up 3.6% from April.

‘Extraordinarily difficult to predict’

Why is strong goods spending coexisting so easily with strong services spending, keeping U.S. imports demand historically high?

Lars Jensen, CEO of consultancy Vespucci Maritime, told American Shipper, “Eventually, it appears highly likely that consumption patterns will indeed get back to normal, meaning more spending on services and less on goods than we have seen in the past 12 months.

“But right now, that is not the pattern seen and there are likely a multitude of reasons, one being the stimulus checks boosting spending, another being how the consumers will be using, or not using, the added savings.

“The timing is extraordinarily difficult to predict,” said Jensen.

“In the data series from 1959 to now — essentially matching the entire history of container shipping — there has been a slow gradual shift from goods to services. The sudden ‘jump’ from services to goods seen in 2020 lies outside any past jump seen. This means there is no historical precedent to help guide us on a timeline.”

Services spending should grow further

One timing factor noted by Bingham is that the recovery in spending on services is not complete, so the predicted shift away from goods spending still has room to materialize.

“Services consumption is not back to where it was, so we still have households that are spending less on services, which gives them more headroom to spend on goods at a higher rate than before the pandemic,” he explained.

Restaurants and vacation destinations remain constrained by lack of staff. “Employment in the services sector is below the desired level, so there are limits on spending, not just because households are willingly not spending, but because they cannot book the date they want to book for that spending to happen.”

‘Too far in the hole’

But even if consumers were not limited on services spending, and even if they did suddenly shift to lower goods spending, there’s still the restocking issue, which should keep import demand strong over the months ahead.

“You would not, under normal conditions, run your inventories this low on purpose,” said Bingham.

Inventories have been pulled down by strong consumer spending combined with “problems in the supply chain, not just on the transportation side, but also on the production side. Not only do retailers and wholesalers not have the inventory they want because they can’t take possession of the inventory they’ve ordered, but in some cases, they can’t even place the orders. Producers are saying, ‘We’re not going to accept your order. You have to get in line.’”

Furthermore, when a shift from spending on goods to services does occur, there will be a lag before importers pull back on orders.

“In a crisis inventory management situation like this, with inventories too low, you’re not saying, ‘Well, we want to be moderate in our ordering because there may be a slowdown [in demand].’ With stockouts and customers yelling at you, nobody’s trying to gauge it and time it and say, ‘We need to be more conservative.’

“And even if consumption were to go down [due to a shift to services spending], seasonal factors don’t just go away,” added Bingham. “There is still going to be back-to-school spending. There is still going to be holiday spending. We’re now getting to the end of June. We’re starting to get into peak season. So, the idea that there will be any kind of lull in ordering seems implausible.

“I think the stockout story is just going to continue. There’s no solution that will allow companies to suddenly rebuild inventories to desired levels by December. We’ve got too far to go. We’re collectively too far in the hole.”

There are global factors to consider, as well. The worldwide availability of container equipment is a major driver of freight rates. Numerous economies are much further behind the U.S. in terms of vaccinations and recovery.

“There are big economies in India and other places that are still suppressed [by COVID],” noted Bingham. “You should see additional demand [when they open up] for the global allocation of the container equipment fleet. Some parts of the global economy are not at the same level of recovery as we are, which is why I am sure this story is still going to be alive in 2022.”

Click for more articles by Greg Miller

Related articles:

- Rise in trans-Pacific spot rates is relentless — and accelerating

- Home Depot has it’s own ship. That’s an ominous sign

- Time to start prepping for Christmas shipping capacity crunch

- Top 10 liners control 85% of the market — and they’re not done yet

- Inside container shipping’s COVID-era money-printing machine

- Why stratospheric container rates could rocket even higher