After California, New Jersey is the next battleground for trucking’s owner-operator business model. And motor carriers fear the war there may be largely lost.

The latest skirmish centers on a report that New Jersey Governor Phil Murphy commissioned from the state’s labor department and other agencies about employee misclassification.

Trucking, along with janitorial services, construction, home care and delivery, was listed as one of the industries where employers “can gain a competitive advantage by driving down payroll costs” through the use of independent contractors rather than full-time employees.

The report said independent contractors are deprived of overtime, worker’s compensation benefits, sick leave, the right to unionize, and other rights afforded to full-time employees.

Its recommendations include new laws that give the New Jersey Department of Labor and Workforce Development more enforcement power and access to tax records, increases fines and makes any company that subcontracts to a New Jersey firm liable for any misclassification.

The last item draws specifically from the drayage liability law that went into effect this year in California. The law allows the state’s department of labor to lists carriers that have outstanding court judgements due to unpaid wages or similar claims.

Gail Toth, executive director of the New Jersey Motor Truck Association, said the report’s “recommendations make it nearly impossible for anyone to be an independent contractor.” She put the blame squarely on the administration of Governor Murphy, who said during his campaign that he wants to make New Jersey ‘the California of the East.’

She added, “Governor Murphy is not taking into consideration that this is a choice of some people to control their hours and schedule. He refuses to believe that there are poeple doing this on their own.”

Toth said that report is part of an ongoing effort to make the state a more difficult place for trucking companies to operate.

In 2018, New Jersey ended the ability of motor carriers to use the Internal Revenue Service’s 20-factor test for determining employee status. Instead, New Jersey now requires the ABC test as established by the Dynamex case in California.

But the ABC test is much more difficult for motor carriers to pass due to the federal requirement imposed by the Motor Carrier Safety Act, said Salvador Simao, who specializes in labor and employment law at Ford Harrison.

For example, the first prong of the ABC test is that drivers are essentially free of the control of the employer, except for their specific contract. But New Jersey’s labor department said the exclusivity and drug and alcohol requirements in federal statutes determine that motor carriers do not meet the first requirement.

The last prong that drivers are in an “independently established trade” has also been rejected by the labor department due to rates being negotiated pre-trip and to motor carriers helping owner-operators obtain required workers’ compensation insurance.

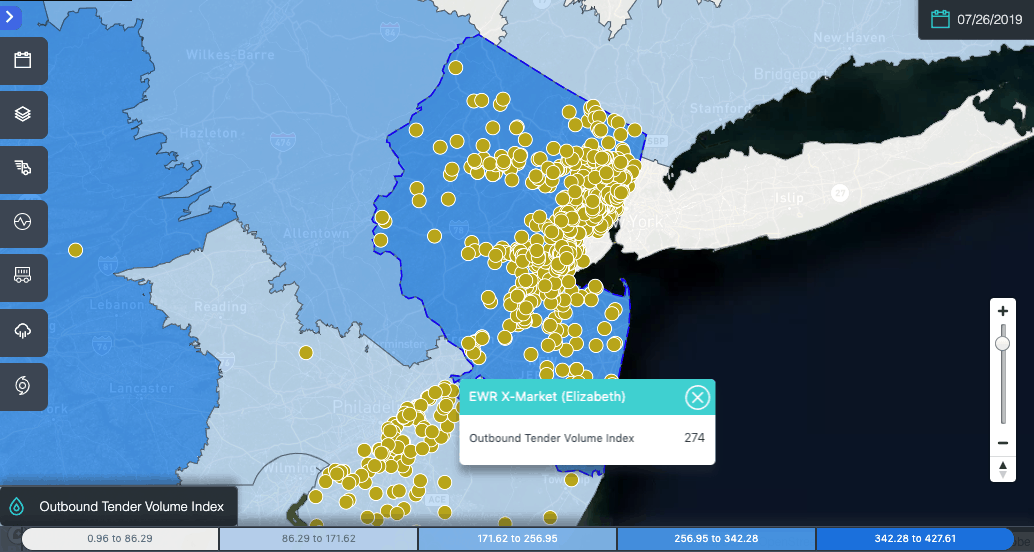

Toth said drayage carriers take the hardest hit from limiting the use of independent contractors due to the variable demand of container flows off the ports. She estimates that up to 5,500 of the 8,000 drivers that regularly call on New Jersey ports are independent contractors.

Toth is doubtful that the current administration in Trenton will do anything to make the process of hiring an independent contractor easier.

“We have done everything,” Toth said. “We have talked to every legislator, the governor’s staff. We have legislation to protect the status of independent contractors, but we can’t get it on a committee hearing.”

Simao agrees that New Jersey’s motor carriers face more regulatory risk in wage and labor disputes. He points to a June 2019 decision in a New Jersey appellate court case that held Cream-O-Land Dairy liable for wage violations despite being advised by New Jersey labor inspectors that it was in compliance.

Despite a superior court judge finding that advice from the labor department barred liability, the state’s Attorney General filed a brief on behalf of the drivers saying that Cream-O-Land could not use those three determinations in its defense.

With legislative relief unavailable, “what’s left is attempting to win in the courts,” Simao said.

His firm is representing intermodal carrier Eagle Systems in a class action lawsuit filed in December 2018 that seeks to declare unlawful the way New Jersey’s labor department classifies a driver.

“The way New Jersey is enforcing the law should either be preempted by federal law, deemed unlawful as a violation of substantive due process, or both,” Simao said.