You all loved the May 19 article, “Giant container ships are ruining everything.” So, we’re delving deeper into the topic. This week’s MODES features special guest Olaf Merk.

One could call Merk the original Big Boat Disrespecter. He is the Paris-based administrator for ports and shipping at the International Transport Forum of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Merk has led several research inquiries exposing the issues of megaships over the past decade. He was kind enough to take an hour out of his day to chat with MODES about the issues with giant container ships.

A note: Our conversation was recorded before the Federal Maritime Commission’s final report on competition in international shipping, which … um … asserted that the ocean shipping market is not concentrated. I included his comments on the FMC’s report at the bottom of this newsletter.

As a reminder, the top 10 ocean carriers control 80% of the industry. Nine of them are further organized into three alliances. In 2021, they earned $150 billion in profits.

Enjoy this lightly edited transcription of my conversation with Merk.

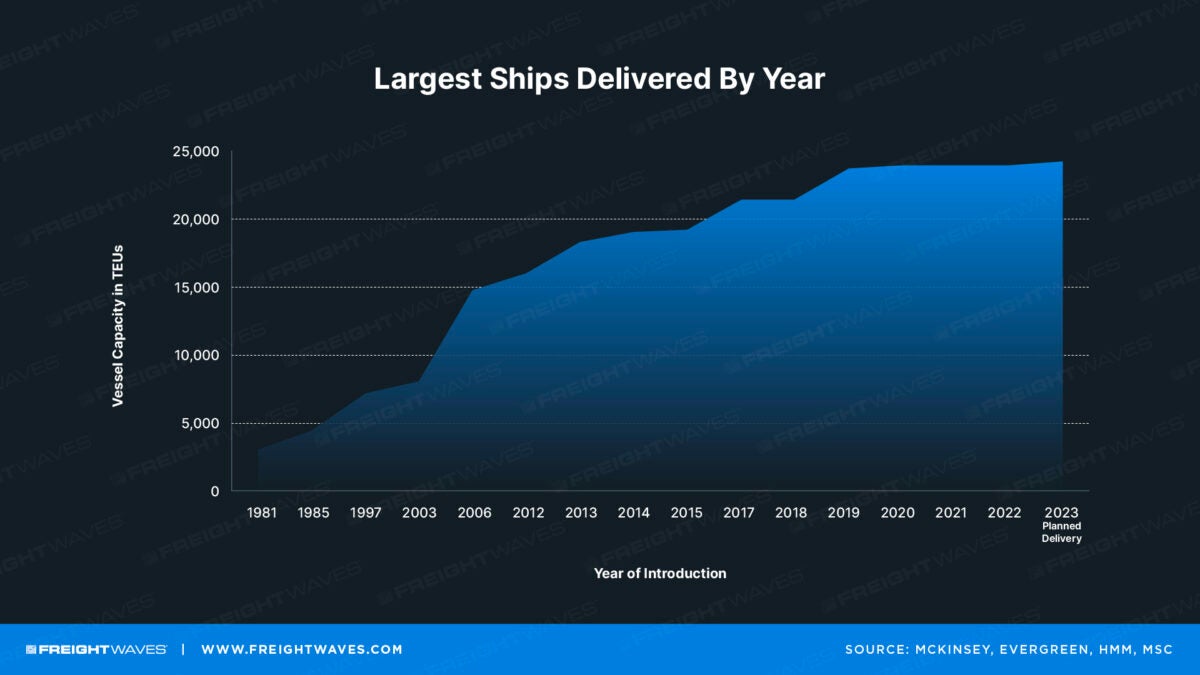

FREIGHTWAVES: Through the 2010s, ocean carriers continued to build larger and larger ships even as ocean rates and trade volumes were falling. What motivated that?

MERK: “I think that was the choice of one carrier [Maersk] to use an even bigger class of ships and kind of as a weapon to get some of their competitors out of the market. It is about a slightly lower cost, but also I think that many competitors would not be able to follow that race to ever-bigger ships.

“It seems kind of paradoxical that [Maersk] timed that when trade was still recovering. But I think that was also on purpose. Some of their competitors were still having financial problems. So, I think that was the original calculation.

“Of course it didn’t exactly work out as they planned. That is this whole story about alliances. Some of the carriers also decided to join alliances and actually order these new ships with their alliance partners. But I think that is not what was anticipated.

“But the end result is still more consolidation. We saw rounds of consolidation and mergers and acquisitions and bankruptcies. We saw that all the top carriers work more closely together.

“In the end, we have a more consolidated field with fewer players, and I think that was the intention.”

FREIGHTWAVES: Some of my piece touched on the clash between these ships getting larger and larger even as ports, especially in the U.S., might not be keeping up. What is happening from an international perspective? Do megaships become more economical if ports keep up in size and innovation?

MERK: “Well, I don’t think they would be economical if ocean carriers needed to pay for the adjustments in ports and terminals. The fact is that they don’t, so that is why it has been economical so far.

“The ports essentially take it for granted that they cannot recover all their additional investments that they have to make. I think that is the essential point, why ships were still getting bigger. But I think if carriers were obliged to pay for the bigger cranes or the dredging, then I think it would show that it doesn’t make sense for them to go bigger. That is also in our own report in 2015, where we calculated that the cost for a whole transport system, of going bigger, was higher than the cost savings for carriers. So that is essentially the mismatch that exists.

“This is an effect that is relevant for all ports throughout the world, actually.

“Let’s say that the biggest ships were intended to go between Asia and northwest Europe. All the focus has been on these ports and how they adjusted dredging in Hamburg, Antwerp and the EU port extensions brought to them. But all ports are seeing the effects of bigger ships. If you have [megaships in Europe], they also go over trans-Pacific. That means that also in North America you’ll see the need to upgrade ports. The ports that were trans-Pacific, they will build bigger in other rounds.”

Shipping giants play global ports against each other for better infrastructure — and avoid footing the bill

FREIGHTWAVES: Could you talk a little bit more about how this plays out in the developing areas of the world, outside of Europe or North America?

MERK: “The challenge is similar in many places of the world. The capacity or the willingness to [accommodate megaships] is probably something else.

“For example, we looked at the ports of Buenos Aires in Argentina and some of the other Latin American ports. What we found there is that they didn’t do a lot of adaptations to their ports. In that case, it was more the carriers that actually adapted some of their ships to the specific ports, or the shallow depth of some of these ports. They actually developed a specific Latin American ship for that route.

“Generally I think most of the ports, they don’t have a lot of choice. They are becoming trapped in a competition with their competitor ports in the same region. Because the port that actually is going to do the necessary investments, they get promised, let’s say, a lot of the cargo.

“Generally I see in a lot of ports these kinds of games where carriers threaten to go to another port, unless the port invests in, well, whatever you want. Most of the time that is of course bigger terminals or terminals adapted to bigger ships.”

FREIGHTWAVES: It reminds me of an issue in the U.S. where you see various small counties and towns, especially in more rural America, will offer these major subsidies for Amazon to build a fulfillment center in their town, in their municipality. The thing is that Amazon was going to build a fulfillment center there no matter what. So they’re losing out on tax revenue for something that was going to happen whether or not they offered all these sorts of tax subsidies.

It sounds like for the ocean carriers it’s similar — whether or not you offer these sorts of benefits, the ocean carriers need to go into these certain regions.

That’s kind of a long way of asking my next question, which is, why do countries provide all of these tax benefits when these ocean carriers are going to go to those places anyway? It’s not as if they weren’t going to be servicing certain countries, whether or not there were tax benefits. Could you explain a little bit more about that?

MERK: “It is indeed, I think, a comparable mechanism to your point about Amazon and the different states — with the difference that this is probably not a monopoly but an oligopoly.

“There’s several players, but they work together in alliances. Especially if they operate in alliances, of course that represents a big chunk of the traffic of certain container ports. So that is one side.

“The other side is that the ports want to continue to be a big port and want to continue to be in, let’s say, the Champion Leagues of the ports. They consider the other ports in the region to be competitor ports.

“If you have, let’s say, the top 10 ports in Europe and the top 10 ports in Asia or in China, and if they would say, ‘Well actually, we’re not going to do this any longer. We’re not going to adapt to every round of new types of ships,’ I think that would end the race to have the larger ships. It would just require, actually, the coordination of some of the large ports or of the states that represent these.

“I think that that could have happened a few years ago, when China wasn’t really that sure that megaships were a good idea. At that moment the European Commission would have engaged in talks with China about this. I think they could have reached some sort of an agreement on ‘Well, maybe this is where to stop. Maybe this is the maximum that we think is desirable.’ I think that could still happen, but I think it’s a bit less likely than it was then.

“It is because there is a lot of competition between these ports, and sometimes the competition is so intense that some of the port authorities actually don’t see what they have in common. What they have in common is that no port really has an interest in having these very big chunks of cargo suddenly in their port that then they have to evacuate as quickly as possible.

“If you would ask a lot of the port directors on what are the kind of ships they would ideally like to see in their ports, I think if they’re honest, you’ll probably hear something like, ‘Well actually, we would prefer two 12,000-TEU ships instead of one 24,000 ship,’ because you’ll be able to spread it more evenly over the day or over the terminal. You’d be much more flexible than you are if you have to continuously serve these very large ships.”

China wanted to push back on megaships, but the European Commission wasn’t interested in chatting

FREIGHTWAVES: I wanted to go back to something you said just now. You mentioned that there was a point a few years ago when China wasn’t sure that megaships were a good idea. And at that moment, the European Commission could have reached an agreement and maybe altered or maybe even put some sort of stop to these ships getting bigger and bigger. What happened?

MERK: “That was at the point when China, and Cosco in China, didn’t really invest in the larger ships yet. Some of the ports like the Port of Shanghai were saying, ‘Well actually, the ideal ship for our port is the 14,000-TEU ship.’ I went also to some of the meetings with some Chinese officials, and there was really a kind of newer view on some of these megaships. I don’t think that’s changed that much.

“I think what we changed was the fact that the European Commission didn’t seem to be interested in discussing this. They thought that, well, it’s actually the European carriers that started all this, and it is in their interest. That is, I think, how they perceived the discussion. From that, I figure that China concluded, OK, well if that is the case, our carriers are also going to [build these megaships]. And this is what the play is going to be.

“Essentially because the European Commission could have approached this question differently and thought of it, let’s say as a question of importance for a whole transport chain or whole transport system. So thinking about, what happens if you introduce a lot of these very big ships into the system? What happens to ports, to the logistics system, to transport networks? I think that should have been the consideration.

“Of course then you get a different conclusion than if you were simply looking at, well, what are the carriers that are ordering that, and are they European or not?”

The three big ocean alliances are also … allying with each other

FREIGHTWAVES: It seems like an essential issue here is that the ocean carriers of the world are aligned, but none of the ports are. The carriers can work together in some ways, but the ports are in this race to the bottom.

Is that an accurate summary? Or maybe it’s more complicated than that?

MERK: “There are some ports in some parts of the world that have actually merged, such as Seattle and Tacoma [Washington], and there are some Japanese ports that have merged. Recently in Belgium, you got Antwerp and Zeebrugge that have merged. There is a bit of movement there, but of course it is much less than what happens in ocean shipping.

“What is generally underestimated is the extent to which ocean carriers incorporate not only in alliances, which is one thing, but also across alliances. This is what we found in a recent study, where we looked at all corporation agreements between the large carriers. That also includes vessel-sharing agreements or consortia, as they call it in Europe.

“Around a quarter of these corporation agreements are between the top 10 carriers that are not in the same alliance. What we conclude from that is that it’s the alliances that are dominating shipping. But actually there are a lot of links, a lot of bridges among the carriers that are in these alliances.

“You could really say that, to some extent, this is actually one big conglomerate with a lot of cooperation among the different carriers.

“And it is clear that no port on its own is strong enough to really confront these carriers. So yes, you really need some sort of cooperation among ports, if you want to put something in place that is more, let’s say more in the public interest rather than in the private interest of carriers.”

We — the taxpayers — have been unwittingly paying for worse and worse ocean shipping service

FREIGHTWAVES: OK, that’s interesting. So there are not just the three big alliances, but also the three big alliances even have an alliance among each other.

I think we can all agree on the surface that, when we see this lack of competition, it immediately strikes most people as harmful and maybe something that we should avoid for consumer welfare and all these other issues.

What is kind of the bottom line? What is the true effect of these alliances? Does this result in higher rates? Does this result in less efficiency?

Some people might argue that these alliances are really just because the economics of ocean shipping are so complicated, and they really have to collaborate in order to make this all work. What have you found in your research that concludes why these alliances may be harmful?

MERK: “On that point, yes. They might need this form of cooperation, but that is also because they wanted these big ships. There essentially is no need for alliances if ships were much smaller. The reason why we have these alliances and why we have all these other forms of cooperation is because the ships have been so much bigger.

“Imagine a situation in which, instead of 24,000 ships, you have 10,000-TEU ships. Then it is much easier for a single carrier to offer one global network of connections that they cannot do at this moment, because they don’t have that scale. That’s one thing.

“But I think the biggest impact is on public infrastructure. Ports are essentially played out against each other and the taxpayer pays the bill. It’s not the carrier that’s going to pay for the dredging. “In theory it is, because they need to pay harbor dues or things like this. But if you look at it a bit more closely, you’ll find that carriers are actually not paying the whole bill. A lot of it is actually also coming from public money.

“Let’s say the taxpayer pays this. What does he get in return?

“Actually, not a better transport system. It doesn’t get more connectivity or more services or more reliability — especially the last few years. But this is a longer trend where you see that the connectivity has gone down. The number of services from Asia to North Europe or North America has also decreased. It’s not like the services have become better.

“Obviously taxpayers don’t know this, but you wonder why would they pay for something that hasn’t actually improved? I think that is a big problem, and that is related, of course, to this ever-stronger position of carriers, because they can essentially put ports or governments in the position to pay for this.

Shipping giants may have been canceling sailings for far longer than necessary in 2020 — and it helped increase their rates

MERK: “Does it have an impact on consumers and on the price of maritime transport? Well that of course is the question now, and especially since we’ve seen this huge increase in freight rates. It is difficult to prove, of course, and this is also why many competition authorities are looking into that, but are also having difficulties finding, let’s say, a smoking gun.

“But at the same time there are certain episodes in this whole story over the last two, three years where you could wonder if it isn’t really the cooperation among a lot of the carriers that has created the situation in which we are.

“For example, look at the timing of blank sailings during economic lockdowns and the period over which these blank sailings were taking place. In our view, when we look at the numbers, the period of blank sailings seems to be much longer than would probably have been justified, if you look at the freight rates. A lot of capacity was idle, so a lot of sailings were blanked in spring and summer of 2020. But if you look at freight rates, they started to go up in May and June of 2020. But it’s actually only September 2020 that capacity was back to normal.

“That is just one example, where you could think that actually the joint capacity management of carriers had an impact on the scarcity of capacity and thus on freight rates.

“There are other episodes where I think competition authorities could really look into what happened and wonder if all the cooperation that they allow carriers to carry out, if that hasn’t also had effects on supply chains that are not in the public interest.”

FREIGHTWAVES: The smoking gun point is interesting, because I think we all kind of picture that this sort of cooperation would happen in back rooms where these sorts of collaborations are happening. And there seem to be episodes of this. But it also seems like even the bigger issue with this competition, especially pre-COVID, is just the idea that taxpayers unknowingly have been paying for more dredging, more port improvements, and they weren’t even realizing that they’ve been subsidizing a service that has essentially gotten worse.

What would be the expected smoking gun that authorities are looking for? What are authorities looking for, that they haven’t found evidence for so far?

MERK: “I don’t know exactly what competition authorities have done behind closed doors. I can just see some of their statements, and they’ve done some inquiries that are public. But I would be interested to know from these authorities if they looked into these kind of these episodes and have asked carriers simply what is their explanation and then if that makes sense.

“What I’ve seen so far is that there have been explanations for certain situations that have been simply too easy or not correct or not accurate. But authorities still seem to buy that. It’s a difficult question to answer, because as I said, I don’t know exactly what they have been doing behind closed doors. But I think it would be great if several competition authorities would at some point look back at this whole situation that we have seen since COVID and try to really and honestly make sense of it and not simply repeat a carrier’s lines or carrier explanations.

“We’d be interested in seeing explanations. And well, as long as that isn’t really given, it remains a bit unsatisfactory.

‘Victims of a global play’

FREIGHTWAVES: Would you say there’s any country or any port authority that’s doing it differently? On the carrier side, I know Zim is one of the carriers that’s not in any sort of alliance. I’m curious if on the port side you can think of any sort of port authority or country that’s just not getting involved in the whole game of supporting these ports and kind of bending over backward for these carriers.

MERK: “This whole story is a story of the bigger ports. There’s a whole range of secondary and tertiary ports, where actually the big carriers don’t really go, so they’re not really interested in those ports in a way. I think that is also a blessing. I think these are the ports that are more structured according to what the regional economy needs rather than being structured according to the wishes of a few global carriers.

“In Europe we have the Port of Malaga in Spain or the Port of Taranto in Italy, which were in the global carrier networks or the plants until the moment that they decided to do something differently. Then, these ports had to adapt. And that of course is always difficult, because at some point you have to change into another sort of terminal, maybe more for general cargo. In many cases I don’t think there are a lot of ports that say, ‘Well we had enough of it. We’re going to do something else. We’re going to quit the big carrier container business.’

“In most of the cases, they’re more victims of a global play. But this is completely different for ports that are operating in different environments, where it is more about regional cargo or about coastal shipping or about other types of cargo.”

Record profits and meager taxes for shipping giants

FREIGHTWAVES: Is there anything else that you think my audience of general business readers who are interested in these sorts of topics, anything else they should keep in mind?

MERK: “There are lots of angles. One of the issues is vertical integration. So a lot of the container carriers are now also active in a lot of the other parts of the transport chain. That is in terminals and freight forwarding, logistics, etc. That is one point.

“Another point is of course that which you also mentioned in your article, that they really made a lot of profits over the last two years. When a lot of other sectors were trying to survive, they made record profits.

“I think an interesting element in that whole dynamic is the fact that they don’t pay a lot of taxes. So it’s essentially similar to what you mentioned about Amazon. This is a similar dynamic for shipping companies, where they have managed to pull off some sort of a race to the bottom when it comes to taxation. A lot of these shipping companies and also container shipment companies don’t pay a lot of taxes. I think that is now becoming a little bit clearer and also becoming more flagrant now they’re making these record profits that have an average tax rate around 2%.

“There’s always also discussion about how clean they are, how green they are. There’s an enormous need to decarbonize the sector. Shipping generally uses the dirtiest fuels that exist. Their greenhouse gas emissions are essentially in the order of a country like Germany or South Korea. There’s a lot of emissions that they could reduce. And well, for the moment that isn’t going very quickly.

“It’s a mix of a lot of elements that raise eyebrows, let’s say — the combination of very high profits, low taxation, a carbon footprint that is huge, etc.”

Merk had this comment to share about the FMC fact-finding market analysis (emphasis ours):

“This raises the question of what is a concentrated market. There are various ways to measure concentration. A traditional concentration indicator is the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index, abbreviated as HHI.

“The U.S. merger guidelines consider a market with an HHI higher than 2,500 points to be highly concentrated. In research that we did with MDS Transmodal, we found that 15 out of 33 maritime trade routes to and from North America have an HHI higher than 2,500, so can be considered highly concentrated. But as we have argued in a recent article, these traditional indicators underestimate the concentration in the liner shipping sector, because they do not take into account the effect of alliances and other cooperative arrangements between carriers. In order to correct for this, we calculated modified HHIs, and these turn out to be considerably higher than the traditional HHIs. For example, on the trans-Atlantic route, the traditional HHI is around 1,500 — indicating moderate concentration. However, the modified HHI for the same route is 2,500, which indicates high concentration. On many routes, there are hardly any independent carriers left; those are carriers that do not cooperate in one of the three global alliances. On the trans-Pacific routes, the market share of independent operators in 2021 was around 8%, considerably lower than in 2020, or 2019 or any previous year.”

If you’re interested in learning more about Merk’s research on megaships, check out his papers from 2015, 2018, 2019 and 2020.

Thanks for reading! Please send me a note with your thoughts at rpremack@freightwaves.com and don’t forget to subscribe to MODES. See you next week.