Earlier this month, the CEO of XPO (NYSE:XPO), Brad Jacobs, announced that he intended to divest operating units of XPO in an effort to maximize shareholder value. One thing was clear, however. Jacobs intended to hold on to the less-than-truckload (LTL) operations of XPO that were formerly known as Con-way. As part of our Online Haul of Fame Series, here is a look back at the history of Con-way.

Con-way Freight was founded as a spinoff company by Consolidated Freightways (CF) in 1983.

Previously, Consolidated Freightways’ key business focus was long-haul transportation, with many of its routes averaging 1,300 miles. CF had sold its truck manufacturer, Freightliner, and needed direction about where to invest that money. The company’s management looked to Boston Consulting Group (BCG) to assemble a report and advise on its next investment. The report showed that the most profitable segment of over-the-road transportation at the time was freight that traveled less than 500 miles, and that, in fact, the average length of a haul in the United States was closer to 500 miles than CF’s 1,300.

A decision was made among CF executives to pursue the idea of regional LTL companies, focusing on three regions: Con-way Eastern Express (CEX), Con-way Western Express (CWX) and Con-way Central Express (CCX). Though the deregulation of the 1980 Motor Carrier Act had left several carriers floundering and desperate for a buyout, CF elected to build its companies from the ground up in the West and Midwest. The three new LTL carriers began as independent companies that could only sell freight within 500 miles of a terminal. Their freight could not be shipped to another destination outside of the terminal, even if it fell within the company’s area of service.

CF faced unique challenges when operating Con-way Freight due to its relationship with the Teamsters union. CF was union-affiliated, and the Con-way companies were not. Therefore, there could be absolutely no overlap in their business practices, customers, employees or affiliations, or Consolidated Freightways could be accused of “double-breasting.” Technically, the money used to create Con-way Freight came from Consolidated Freightways’ holding company, and the new companies were safe. However, that did not stop the Teamsters from pursuing them, and each of the Con-way Freight units had to be on guard constantly, refraining from even listing their company names in employment ads.

The 1980s, though challenging for many companies, were an opportunity for growth for Con-way. Con-way Central Express was especially successful, in spite of initial challenges due to a lack of intrastate operating authority. Each of the companies, operating independently with their own management and styles, also ran their own colors, earning Con-way’s fleet the nickname, “the Rainbow Line.”

Since each company operated semi-autonomously, the discussion about the consolidated business should be a story about the regional operating units.

Con-way Central Express

Con-way Central Express (CCX) made its headquarters in a 118-year-old farmhouse in Ann Arbor, Michigan, and sought to service the regional Midwestern LTL market. The company’s first power unit was a 1983 Ford CL-9000 tractor that company President G.L. Detter drove off of the line himself. Con-way Central Express officially opened for business on June 20, 1983, with service to 1,004 points from 11 service centers, including Indianapolis, Indiana; Chicago, Illinois; Detroit and Grand Rapids, Michigan; Minneapolis, Minnesota; Cincinnati, Cleveland, Columbus and Toledo, Ohio; Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; and Milwaukee, Wisconsin. On its first day of business, the company moved 89 shipments and earned $9,696.18 in revenue. Detter soon had his drivers on the road with or without freight in their trailers simply to advertise the company.

CCX had challenges in its first months of operation due to its limited reputation and lack of intrastate operating authority. In the beginning, it was not unheard of for the smallest of shipments to be sent on Greyhound buses and retrieved by terminal managers, if it would be more cost-efficient than sending a truck. Con-way Central grew from 11 terminals to 17 within its first year, keeping the on-time delivery percentage at 95% or higher. The company was averaging 1,000 shipments per day at the end of its first year of business. Growth was aided by the company’s geographic location in the Rust Belt, a region more densely populated than the West or South. The company did not have many non-union competitors and was able to undercut the prices that the companies with unions offered, as well. By 1985, CCX revenues had hit an astounding $1 million per week. The company’s 1 millionth shipment moved one year later.

The Teamsters took special interest in Con-way Central Express after suffering crippling losses of members post-deregulation. The union had become persistent in recruiting members from the CF companies, but CCX remained steadfast, and sought creative ways to keep its employees happy. For example, the company created an incentive compensation program in which each employee would receive a profit-sharing check. Despite being a new company (and this practice often pushing margins into the red), employees, from drivers to dock workers, remained loyal. CCX was also one of the first companies to offer its drivers a five-day work week.

By its fifth anniversary, Con-way Central had become the feather in Conway Freight’s cap, boasting 81 terminals in six regions. It had more than 2,000 employees and averaged 2,000 tons of freight per day. Growth and expansion continued in 1989, with six new service centers in Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, Ohio and Pennsylvania. The total number of terminals increased to 116. When sister company Con-way Eastern Express (CEX) closed, Con-way Central was still going as strong as ever. CCX eventually expanded into some of the territory that Con-way Eastern had left behind, allowing it to remain Conway-owned. Despite union protests, CCX was eventually ceded CEX’s northeastern operating authority. The company extended service further into Pennsylvania and even into Canada.

In 1993, the Con-way companies celebrated their 10th anniversary. Con-way Central Express was the shining star, with approximately $300 million in sales. All of the companies had achieved over 98% on-time delivery to their customers. Con-way Central had become one of the most successful regional LTL companies in the nation. In 1993, Central had 5,000 trucks, tractors and trailers in 153 terminals, servicing 42,000 communities in 13 states and Ontario, Canada. Though a Teamsters strike caused strife in 1994, Con-way Central expanded yet again in 1995, opening additional service centers and terminals in the Northeast and Midwest. Expansion continued in Canada and even Puerto Rico in the mid-1990s. By 1997, the three Con-way regional carriers were projected to earn $130 million in revenue. Company culture, service and growth defined CCX, and as the decade drew to a close, those patterns continued. Con-way found new ways to service customer needs, such as offering guaranteed service and linking the regional services of Con-way Western and Con-way Central to provide expanded inter-regional service for the first time.

Con-way Southern Express

In 1986, parent company CF Land Services announced its intention to open an additional regional LTL carrier to service the Southeast. The carrier, Con-way Southern Express (CSE), opened in April 1987 with Charlotte, North Carolina, as its headquarters and Thomas C. Smith, a Con-way executive, at the helm. Con-way Southern Express benefited from the success of the companies that came before it and opened with 130 employees, 15 terminals, 100 tractors and 300 trailers. Initially, CSE’s service area was Georgia, North and South Carolina, eastern Tennessee and Virginia. Con-way Southern grew more slowly than Con-way Central but mimicked the other regional carrier’s best practices. By 1988, CSE’s Richmond terminal became the company’s first to achieve profitability. Distribution magazine’s annual reader poll named CSE the “quality Southeast carrier of the year” that same year.

Growth continued not only for CSE, but for the other regional carriers as well (with the exception of Con-way Eastern). In 1989, CF Land Services rebranded to Con-Way Transportation Services. At the time, the four regional carriers boasted 232 service centers and 5,700 employees, and they moved approximately 25 million pounds of freight per day. In 1989, another regional carrier was added – Con-way Southwest Express. CSE underwent its own large expansion in 1989, growing from 27 terminals to 40 and expanding service into Florida. Its competitors at the time were giants such as Overnite Transportation, Carolina Freight Carriers and Estes Express Lines, but CSE managed to hold its own, and by the close of the decade it was turning a monthly profit. In 1990, CSE purchased McMinnville and Hohenwald Truck Lines and acquired intrastate authority in Tennessee.

By 1992, the four regional Con-way carriers – Con-way Central Express, Con-way Southern Express, Con-way Southwest Express and Con-way Western Express – operated a combined fleet of more than 11,000 trucks and trailers. That same year, CSE added Puerto Rico to its list of destinations and began handling return shipments from Puerto Rico as well. In late 1992, a plan was also implemented to allow Con-way Southern and Con-way Southwest to interchange freight, something that had been considered all but blasphemous, as it could compete with Consolidated Freightways, an affiliated company. The two companies began to interchange freight in 1993. They were able to expand their market reach without infrastructure or employee investment but were now in direct competition with Consolidated Freightways for longer-haul freight. Soon after, the other regional Con-way LTLs began interchanging freight as well. In the latter half of 1994, new “gray ghost trailers” were introduced, generic 28-foot trailers with gray, as opposed to rainbow, stripes. These trailers were branded Con-Way Transportation Services and were designed to fit in with the rainbow fleets of the other regional carriers at the time.

In 1994, Tom Smith, CSE’s founding president, retired. Rather than choose a successor to run the company in his stead, Con-way Southern and Con-way Southwest merged into one company. A Teamsters strike earlier that year had showered the Con-ways with an influx of freight, opening their eyes to what they could become if they expanded. It made the most sense to do this as one, not two separate entities. The companies merged in 1995. The merged company operated under the name Con-way Southern and operated in 13 states with 101 terminals and over 6,500 pieces of equipment. Con-way Southern celebrated 10 years in business in April 1997. In late December of that year, it was announced that Con-Way Southern and Con-Way Western would now deliver freight across 1,600 miles in just two days as well as three-day service for coast-to-coast shipments. Though regional next-day was still their flagship product and focus, Con-way’s regional carriers were now in direct competition with long-haul providers, and Con-way Southern was no exception. The Con-way regional companies were the most profitable LTL companies in 1998, even more so than ABF Freight Systems and U.S. Freightways.

Con-way Southern Express continued to be profitable and grow until 2007. Rebranding occurred as part of the transition from CNF to Con-way, and part of this rebranding was merging all of the Con-way regional LTL companies. Each company dropped its individual colors and letters and consolidated under the Con-Way Freight banner in 2007. They operated under this until Con-way’s 2015 purchase by XPO Logistics.

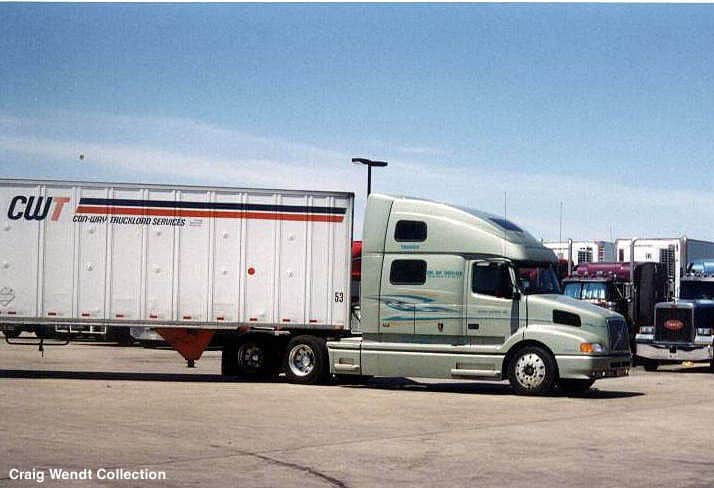

Con-way Truckload Services

Con-way Truckload Services was the name given to the rebranded Con-way Intermodal in 1995. Con-way Intermodal had been founded in 1989 as CF Truckload. This subsidiary company of CF Inc. was based in Fort Worth, Texas. Its main purpose was to provide full-service, multi-modal transportation for truckload shippers. It was made up of rail, ocean and trucking divisions and offered door-to-door domestic transportation as well as international export shipping services to more than 200 container ports worldwide.

Con-Way Truckload Services also provided contract container drayage throughout the United States. Before being rebranded as Con-way Truckload Services, Con-Way Intermodal had implemented piggyback services with major railroad companies. It had also introduced Con-Quest, a program that combined the company’s resources with the resources of major railroads for expedited door-to-door service. Though headquartered in Texas, the company boasted sales offices in Oakland and San Bernardino, California; Jacksonville, Florida; Kansas City, Missouri; Charlotte; Cleveland; and Memphis, Tennessee.

In 1995, Con-Way Truckload Services began providing dedicated regional, inter-regional and expedited highway truckload freight service along with its impressive portfolio of rail capabilities. In 1995, Con-Way Transportation Services invested $25 million in the subsidiary, which added 175 tractors and 150 53-foot highway trailers as well as new technology and tracking systems management. To complement the Con-Quest service, Con-Way Truckload Services added Express Service, which offered expedited next-day and second-day service.

Con-Way Truckload Services did not exist long under that name, however. By 1998, railroad mergers and consolidations had left only four mammoth railroads standing. As such, these railroads had considerable negotiating power when it came to dictating how strictly intermodal companies could operate. At the same time, CNF’s earlier acquisition of Emery Worldwide was proving to be more challenging than anticipated. Costs associated with maintaining Emery’s business ultimately prevented CNF from recapitalizing Con-Way Truckload’s aging fleet of equipment. Parent company CNF elected to dissolve Con-way Truckload Services in 2000, selling off most of its assets. Covenant Transport (NASDAQ: CVTI) ended up buying Con-way truckload, making it part of the broader organization.

Con-way spinoff from CF

The fate of CF and Con-way began to diverge significantly in the 1990s as competitive pressures in a deregulated environment began to take hold.

The price wars that started with deregulation continued to decrease margins, until CF was operating on profit margins of only 1.5%. A Teamsters strike in 1994 lasted 24 days and drastically affected the company’s annual revenues.

Freight analysts began to question if the LTL industry could survive, calling the price wars suicidal and expressing concern about competition from smaller, non-union regional carriers. Rate discounting took a heavy toll on CF’s long-haul business, which achieved profitability only once between 1992 and 1996.

The company elected to spin off CF Motorfreight and four other long-haul subsidiaries in 1996, renaming the group Consolidated Freightways Corporation. The remaining companies – Con-way Transportation, Emery Worldwide and Menlo Logistics – were rebranded CNF Transportation. The “new” CNF Transportation emerged from the rebranding with very little debt, and once again, could focus on its LTL offerings and expertise.

CNF and CF were operated completely differently after the split. CNF was largely a non-union operating company, while the union operations remained with the legacy CF. Following the spinoff, CNF thrived as an independent company, while CF began to struggle.

Con-way’s growth continued for the rest of the next decade. In 2007, the Con-way regional LTL companies consolidated under the Con-way Freight banner, abandoning their own colors and regional names. The company was also now operating a national network, with one of the most competitive service times in all of LTL.

The story of Con-way as a standalone company eventually comes to an end, with Con-way announcing its intentions to merge with XPO in September 2015.

Brad Jacobs, the strategic visionary behind XPO, offered $3 billion for the LTL company. At the time, Wall Street was not impressed, with the stock falling nearly 50% in the six months that followed the deal being announced. Investors were concerned about XPO’s pivot away from non-asset transportation services.

Not all of the pressure on XPO stock could be explained by a lack of confidence in management, however. The freight market was in the midst of an industrial and commodity recession caused by a global slowdown.

Undeterred, Jacobs continued to explain his vision for finding value in finding financial and operational efficiencies in legacy players. The stock bottomed in January 2016 at a little over $21 a share and over the next four years rallied to the mid-$90s. Jacobs continued to insist that shareholders were undervaluing the individual assets, particularly a drastically improved LTL operation that was previously known as Con-way.

We will dive into the history of XPO at a future date. While one would argue that Con-way is still with us as XPO, it is hard to recognize the legacy company in the much newer XPO. XPO has embraced technology and is far more efficient than it once was. What does the future hold for XPO? Who knows … But FreightWaves will be sure to cover it.

If you enjoyed the Online Haul of Fame, check out our past issues:

Jason Miller

Great article! It is wonderful to see FreightWaves writing these pieces to compile a written history of some of the industry’s major carriers. Sadly a lot of information has been lost over the years.

Noble1

From my perspective , the name of that company is a shrewd and clear indication and description in regards to what the trucking racket ,cough, I mean industry is all about !

CON-WAY !

In my humble opinion ……….

Mike Cichocki

Awesome reporting. Thanks. Looking forward to you doing an issue on Midwestern Distribution out of Fort Scott, KS and their start in the early days of deregulation. They also got into an owner operator based LTL model with their Leaseway Express startup.

Last real trucker

Great company till xpo took them over xpo got rid of the all the Conway drivers that were good and hired nothing bone heads,such a shame

David Norcross

Thanks again Craig.

Craig Spencer

By far, the best article I have read on Freightwaves. I started in the transportation industry in 1969 so this brings back a lot of memories of the struggles and successes. The changes brought on by deregulation and the loss of companies like CF, IML and PIE. Being both on the Teamster side and later the management side I had a chance to see and understand the challenges of both.

Good Story, thank you.