Keep a close watch on ship finance in 2020. The amount of capital available to shipowners next year will determine vessel capacity growth in the medium term, and thus, future freight rates.

In addition, near-term service reliability can hinge on funding access. If shipping companies cannot refinance maturing debt, ocean services can plunge into chaos, a la the 2016 Hanjin Shipping insolvency.

If 2019 is any indication, there will be even less capital available to ocean shipping in 2020, it will be more costly to access and capital providers will be more discerning on who gets it.

What’s so unusual is that this funding contraction is coinciding with improved shipping-market fundamentals, particularly in crude-tanker, product-tanker and liquefied petroleum gas sectors. Stronger rates and lower default risks usually open the capital floodgates, creating new vessel capacity that ultimately kills the rate recovery.

Not so this time, at least not yet.

Bank debt down, Chinese leasing up

The shipping industry has traditionally been financed by cheap loans from European commercial banks, complemented by owners’ equity from retained earnings. Today, much less debt is available as a number of European banks have partially or entirely pulled out of shipping, with remaining capacity largely flowing to top-tier owners.

“The cheap, high-leverage bank debt [that second- and third-tier owners] relied upon is no longer there,” said Scorpio Tankers (NYSE: STNG) and Scorpio Bulkers (NYSE: SALT) President Robert Bugbee in a recent interview with FreightWaves.

According to Greece’s Petrofin Global Bank Research, shipping loan portfolios in 2018 shrank to their lowest levels since 2007. Data from U.K.-based Dealogic shows that the volume of syndicated maritime loans in the first nine months of 2019 was down 10% year-on-year.

Shipowners have increasingly turned to Chinese leasing houses to replace European bank debt. Companies sell their vessels and lease them back for a specified period, after which they have an option or obligation to repurchase them.

“The new capital in the market now is Chinese lease finance, which is taking up a lot of the slack from the lending community,” said Bugbee at a Marine Money forum held in New York in November.

Regulatory and environmental constraints

One reason for banks’ retreat is new regulations tightening capital requirements. Banks are adjusting portfolios to prepare for the Basel III and Basel IV protocols, which are yet to be fully implemented.

The very nature of ocean shipping — requiring relatively long-term loans amid a volatile, cyclical market — makes it more advantageous under the new rules for banks to lend to other sectors. At a Capital Link finance forum in 2018, Citi global head of shipping Michael Parker warned, “If Basel IV were enacted, it would kill shipping finance forever or require margins [interest rates above the benchmark] of 10%.”

Environmental issues pose yet another hurdle.

Banks, just like institutional investors, are under increasing pressure to support businesses that rank highly in terms of environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues. ESG-wise, shipping ranks low.

In June, shipping banks handling around 20% of the industry’s senior-debt needs signed the “Poseidon Principles,” under which they will benchmark loan portfolio carbon intensities versus the targeted reduction trajectory endorsed by the International Maritime Organization (IMO).

Carbon-reduction targets have yet another effect on debt availability. Banks’ willingness to provide debt for newbuildings is constrained by uncertainty over how long such assets can comply with yet-to-be-written IMO emissions regulations.

Bugbee told FreightWaves, “Lending in shipping is partly predicated on what the residual value will be. You have to have some conviction on what the asset is worth at the end of [the loan] period. If you don’t, you either have to lower the amount you’re willing to lend up front or shorten the tenor [duration] of the loan.”

With one of the sources for previous shipping overcapacity — cheap European bank debt — increasingly out of the picture, what about the other two culprits: private equity (PE) and public markets?

Private equity

PE was heavily active in shipping in 2010-15, betting on a buy-low-sell-high, reversion-to-the-mean strategy. It didn’t work, to put it kindly. Most shipping markets remained weak until very recently and PE exit strategies were thwarted by the closure of the shipping initial public offering (IPO) “window” (the last U.S. shipping IPO was in June 2015).

As PE funds near maturity dates, fund managers are being compelled to exit positions via “ships-for-shares” deals in which PE fleets are sold to existing public shipping companies in return for stock, not cash.

At a Capital Link forum held in New York in October, Art Regan, an operating partner at Apollo Management, predicted more such transactions in 2020. “The PE investors holding onto ships are kind of worn down. Their options are dropping, so I think we’ll see more of this,” he said.

What’s not expected next year is a fresh wave of PE cash flooding into the sector and funding fleet growth. “The funds that were there before are leaving the shipping industry,” affirmed Bugbee.

Public markets: 2019

Equity raised in public markets played a major role in shipping capacity growth in 2003-07 and 2010-14.

Capital raising by U.S.-listed shipping companies declined sharply in 2019 for myriad reasons: (a) stock investors, like their PE counterparts, have seen shipping bets fare poorly; (b) the heightened focus on ESG is turning investors toward companies perceived as “cleaner” than shipping; (c) U.S.-China trade tensions have created an ongoing sentiment overhang, which has not been fully resolved by the phase-one agreement; (d) stock buying is increasingly “passive,” i.e., through algorithms and exchange-traded funds, which favors large-cap equities (ocean shipping is small-cap); and (e) shipping is often viewed as a subsegment of energy investing, and energy investing has plummeted since 2014.

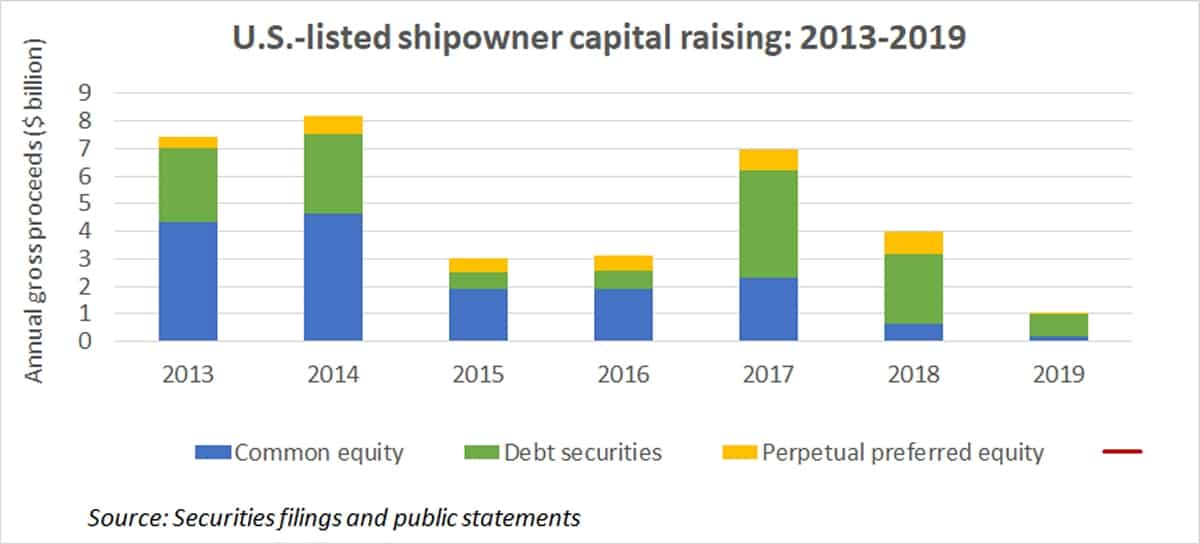

According to data from securities filings analyzed by FreightWaves, U.S.-listed shipowners raised only $1.02 billion in gross proceeds from the sale of securities in 2019 (excluding secondary offerings by selling shareholders).

Only $157 million was from the sale of common shares, with $35 million from the sale of perpetual preferred shares and the vast majority — $828.3 million — from the sale of debt securities (including convertible debt).

U.S.-listed companies raised quadruple this amount in 2018, which was itself a weak year. These owners raised $7 billion-$7.5 billion in both 2017 and 2013 and over $8 billion in 2014. The amount raised from the sale of common equity this year was by far the lowest since shipping developed a substantial presence on Wall Street in the early 2000s.

Public markets: 2020

There was a moderate resurgence of offerings in November in the wake of positive publicity on the historic tanker rate spike. Jefferies analyst Randy Giveans believes more offerings could follow in 2020 if share prices rise enough. “If you get a ratio of the share price to NAV [net asset value] of 120-130%, expect to see share offerings again,” he told FreightWaves in a recent interview.

At the Marine Money forum, Mark Whatley, senior managing director of investment bank Evercore, predicted more offerings ahead.

“Public shipping companies have several reasons to issue shares,” said Whatley.

“They all need more equity. They need more market cap. They need more trading liquidity. They’ve just been waiting for the right stock price to transact. The bottom line is the more optimism, the more it builds confidence in future upside and the more transactions will get done. We think the next 12-18 months present an opportunity to really change the direction of companies [through equity offerings].”

That said, given how low proceeds sank in 2019, next year’s securities offerings are unlikely to rise to a level that creates a significant amount of new vessel supply. It also seems unlikely that shipping IPOs will return in the near future. As Bugbee pointed out, “The majority of the capital on Wall Street now is passive capital” and passive capital does not participate in IPOs.

What is likely in 2020 is that more shipping companies will come to Wall Street either through spin-offs from existing listed companies, as is planned by Golar LNG (NASDAQ: GLNG), or through so-called “direct listings” that use the Spotify (NYSE: SPOT) model, in which stock becomes tradable but no money is raised.

Direct listings brought two large shipping newcomers to the U.S. stock market in 2019 — Diamond S Shipping (NYSE: DSSI) and Flex LNG (NYSE: FLNG) — and more could be en route. More FreightWaves/American Shipper articles by Greg Miller