Almost a week after the collapse of a section of Interstate 95 north of Philadelphia set up conditions for supply chain chaos, that disruption is in the market, but signs suggest that it is at an overall level less than earlier anticipated.

Work on reconstructing the bridge already has begun, with a live cam showing ongoing progress.

Part of the problem in making a clear declaration of the level of stress on the Northeast supply chain is that the roughly 14,000 trucks that reportedly crossed the overpass in the Tacony section of northeast Philadelphia came in all shapes and sizes. A truck going from Baltimore to New York on I-95 can jump relatively easily to an alternate route that might include Interstate 295 in New Jersey or the largely parallel New Jersey Turnpike.

But an LTL or box truck carrier making a delivery in the area near the collapse doesn’t have that many options to choose from.

“The destruction of the bridge has had a significant and immediate impact on transportation and the local community,” Bart De Muynck, the chief industry officer for supply chain software provider project44, said in an email to FreightWaves. “The immediate consequence was the closure of the affected section of I-95, leading to major disruptions for commuters, businesses — and freight movement. Alternate routes quickly became congested as traffic was diverted, leading to longer travel times and increased frustration among motorists. These disruptions can have a domino effect, leading to financial losses and potential setbacks for industries operating in the region.”

But an official at an LTL carrier that works in the Northeast saw it differently. Requesting anonymity for both him and his company, the executive said if 10 was the ultimate level of disruption on a scale of 1 to 10, what his company has seen since the Sunday collapse was likely to be on the level of a 5.

Although utter chaos has been avoided, he did say the closure of I-95 was one of the biggest disruptions he had seen in his freight tenure. But there have been snowstorms and nor’easters that have had bigger disruptions to freight traffic, he added.

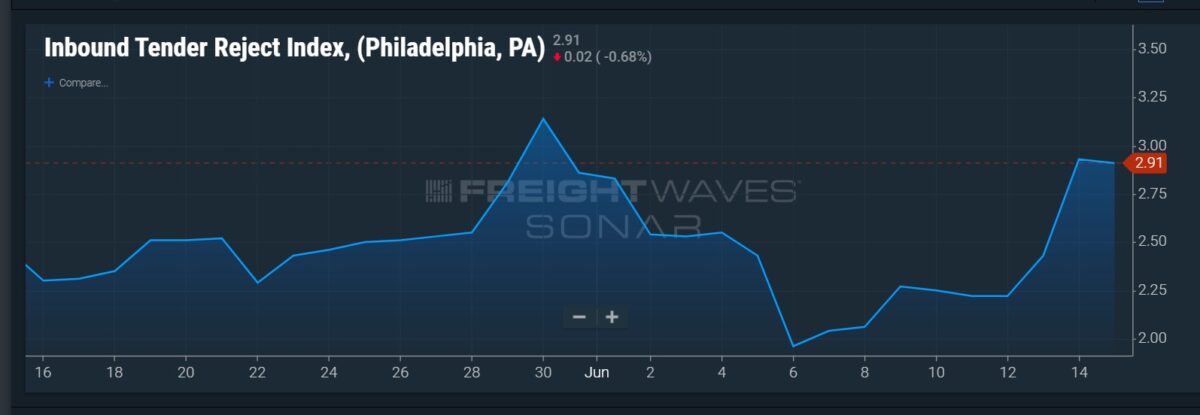

There are signs within data from FreightWaves SONAR that show there are changes in the market but not at an enormous level.

For example, if drivers are choosing not to travel to Philadelphia by deciding not to lift freight destined for delivery into that market because they want to avoid rerouting around the I-95 closure, that action would likely show up in the Inbound Tender Rejection Index (ITRI) for Philadelphia.

The ITRI for Philadelphia has risen. It was 2.22% on Sunday, the day of the collapse. By Friday, it had risen to 2.91%. The national ITRI during that period rose to 3.19% from 2.88%. In the case of Philadelphia, that’s a 31% jump. Nationally, the increase is 10.7%.

The Outbound Tender Rejection Index (OTRI) for Philadelphia would be the opposite side of that coin, reflecting capacity that will not take freight departing Philadelphia for whatever reason, including the shutdown of I-95.

The change in the Philadelphia OTRI is smaller than the ITRI. The Philadelphia OTRI since Sunday rose to 2.01% from 1.74%, an increase of 15.5%. The national OTRI during that time rose to 3.17% from 2.85%, an increase of 11.2%.

The traffic going into Philadelphia is finding congestion, De Muynck said. “According to a major LTL carrier I recently talked to, all trucks had to go through the center of Philadelphia, taking up significant time and causing further traffic jams and impacting on-time delivery for customers but also causing increased costs and loss of efficiency.”

But that traffic going into central Philadelphia would not be able to benefit from the north-south alternatives across the river on I-295 and the New Jersey Turnpike.

Those disruptions add up. De Muynck said the closure “likely will result in tens of millions of dollars in losses to the transportation sector.”

Data provided by project44 shows clear reaction to the closure at first but some signs that delays have retreated since the first days after the closure.

A chart that reflects truckload on-time performance in the Philadelphia area sees that measure actually shooting up to more than 84% on the day of the collapse, plummeting the next two days but then rebounding by midweek.

A chart of on-time performance in last-mile deliveries is up and down, dropping for outbound shipments after the closure but rising for inbound shipments to be roughly equal by Wednesday. The project44 lead time, which measured the median amount of time from when a shipment is picked up to when it is delivered at its final destination for that particular lane, also shows no consistent deterioration.

The official detour around the collapsed bridge is all on Pennsylvania roads, swinging the driver to the west before moving north or south. But a second detour was mapped out Thursday that appears to run primarily on frontage roads parallel to I-95.

At approximately 4 p.m. Friday, the information page for the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation, 511pa.com, showed the local road detour as taking 42 minutes from start to end, while the initial detour was 54 minutes in length.

A collapse of this magnitude 20 years ago would not have come with the navigation tools now available to the drivers of cars and trucks. Decisions on routing a vehicle around the closure can be undertaken by widely used apps for individuals, such as Waze, or more elaborate routing systems that fleets use, provided either by an outside vendor or developed in-house.

One provider of alternative navigation software is Trimble (NASDAQ: TRMB). In a statement, Trimble product manager Kelly Loizos said the company’s navigation applications “have been updated to reflect this significant closure.”

The statement was made as part of an offer of complimentary access to its PC*Miler product, which provides navigation to its users.

Rishi Mehra, vice president of product vision and experience at Trimble, said the company’s navigation tools are seeing the impact of the closure over on the New Jersey side of the Delaware River. “We are seeing excessive truck traffic flow over onto the New Jersey side on 295 or the New Jersey Turnpike,” he said in an email to Pennsylvania. For areas that “need to be serviced” elsewhere in Philadelphia, “there is traffic flowing over onto local roads.”

Beyond that, routing software can take trucks around closures, the trucking executive said, “but there are limits to the effect of that when everybody is going the same way.” And while options such as I-95 and the New Jersey Turnpike are available to trucks heading long distances, trucks making localized deliveries or heading to a regional LTL service center might encounter roads closed to truck traffic even on normal days.

In an article Friday on NJ.com about spillover traffic into New Jersey, Branislav Dimitrijevic, a New Jersey Institute of Technology assistant professor, said that he had looked at both Waze and Google Maps to see what they recommended.

The outcomes on those services, Dimitrijevic told NJ.com, were completely different from the official detour. Northbound traffic involved taking another bridge across the Delaware River near Philadelphia, the Betsy Ross Bridge, as well as some local roads. The southbound rerouting was relatively close to the official detour.

In a separate discussion with FreightWaves, Dimitrijevic had praise for both the New Jersey and Pennsylvania transportation departments. “They have a lot of tools in their box to deal with these things,” he said.

The NJ.com article made two other key points about traffic rerouting:

— It quoted a spokesman for the New Jersey Department of Transportation as saying there had been a “slight decrease” in traffic on Interstate 676 in Camden, which is part of the official detour recommended by the state, and a “slight” increase in traffic on I-295 in Mount Laurel and Route 38, which connects with 295 near Mount Laurel.

— State Assemblyman Bill Moen, who represents a New Jersey district traversed by I-295, said his routing tools have been keeping him off I-295, and his wife’s daily commute has been rerouted as well. “Moen also said he’s seen more trucks and 18-wheelers using I-295 in the middle of the day while he was traveling,” according to NJ.com. “The additional 18-wheeler trucks were definitely a surprise to me,” he said in the article. Unlike the New Jersey Turnpike alternative, I-295 in New Jersey does not have tolls.

More articles by John Kingston

NLRB decision in opera case favors defining workers as employees, not ICs

Labor Department’s independent contractor rule not likely anytime soon

C.H. Robinson hangs on to S&P debt rating but outlook now negative