There have been pandemics before, but never at a time when the global economy was this interconnected. There have been global recessions before, but never one driven by the mix of forces seen in 2020.

With all the uncertainty, there’s an intense hunger for leading indicators. Ocean shipping — particularly container shipping — has offered an early warning system ever since the coronavirus crisis began in late January.

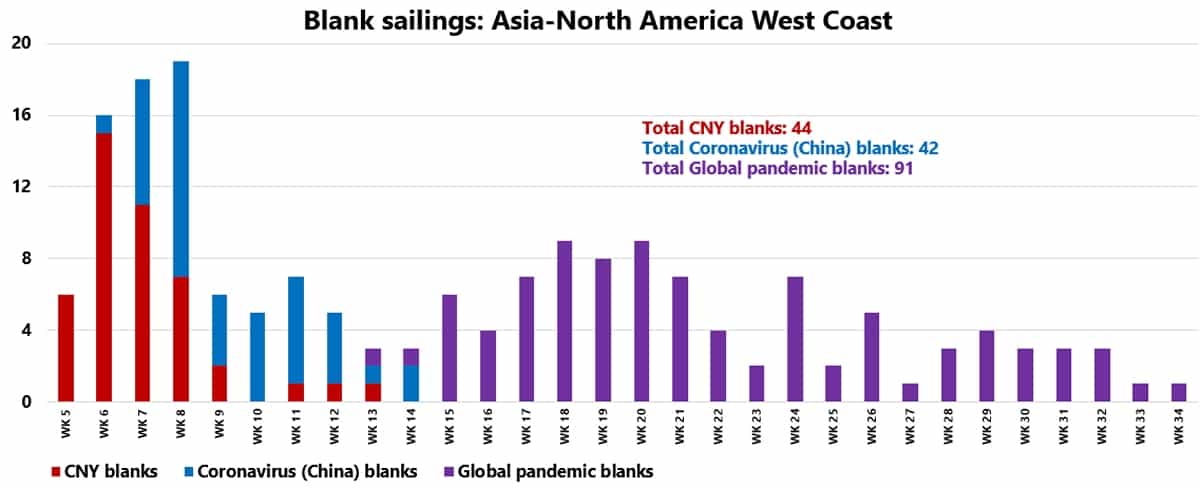

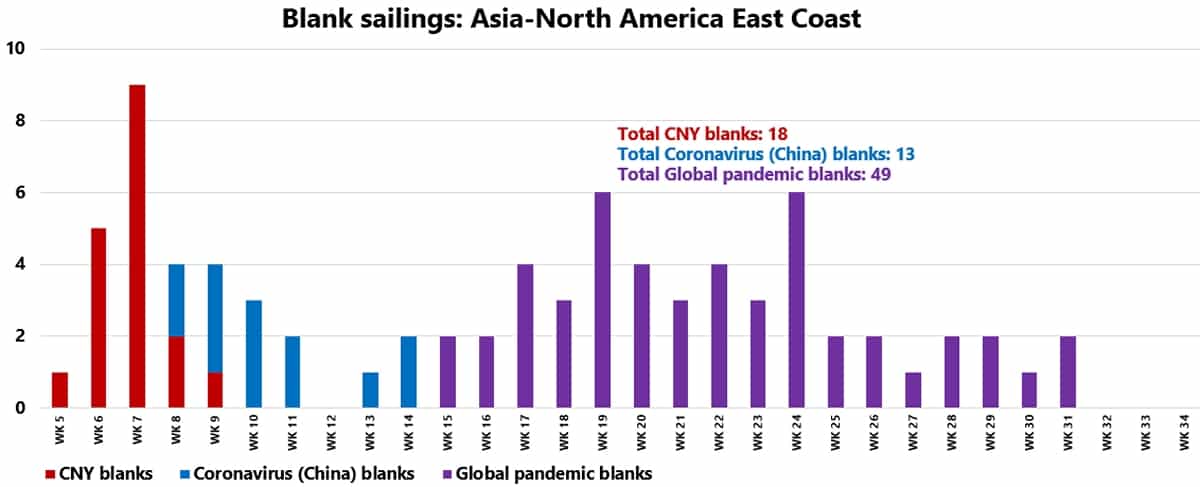

Container lines “blank” (cancel) sailings well ahead of scheduled departures if cargo bookings are too weak. Ships take two weeks to sail from Asia to the U.S. West Coast, four weeks to the East Coast, and five weeks to Europe, so cargo shippers must make booking decisions early.

Analyzing carrier service cancellations provides a window on those decisions, and thus, on forward demand.

One of the world’s top providers of blank-sailing data is Copenhagen-based Sea-Intelligence. FreightWaves interviewed Sea-Intelligence CEO Alan Murphy on Wednesday. The following is an edited version of that conversation.

Strong leading indicator

FreightWaves: We’re seeing huge interest in blank-sailing data, not just from people in the container business. Are you seeing that same increase in interest, and how strong of a leading indicator do you think this is?

Murphy: “There has always been interest, but there has been a massive increase in the last couple of months.

“Blank sailings are a very strong leading indicator. There’s a very, very strong correlation — we calculate about 85% — between blanked capacity and actual demand [declines]. And blank sailings have probably become an even better indicator in recent years as carriers have become better at capacity management.”

In other words, if carriers cut 20% of the capacity on a route, and can keep the ships full, then it could indicate something in the vicinity of a 20% demand drop. But if carriers cut capacity by 20% and slot utilization on the remaining ships sinks from 90% to 70%, then the blank-sailing data would undercount the demand loss and wouldn’t be as good of an indicator.

“Exactly.”

Consolidation effect

The reason carriers have been able to better manage capacity, making blank sailings a better bellwether, is that the field of carriers has become so consolidated. You can see how well they’re matching capacity to demand by the fact that freight rates haven’t fallen due to the coronavirus.

“Freight rates have remained surprisingly strong because the carriers have been very, very strict in their capacity management. This hasn’t happened before.

“In the past, you had 20 global carriers all vying for business and if there was even an inkling that rates were somewhat firm, they’d throw in extra capacity and drive the rates down. If everybody underbid each other by $5 [per container], there were 20 players before consolidation, so suddenly that’s a drop of $100. I think that if we still had 20 carriers today, a quarter of them would be bankrupt by now.

“What’s happened is that we effectively have three entities left [the three East-West-trades carrier alliances: 2M (Maersk, MSC); THE Alliance (Hapag-Lloyd, ONE, Yang Ming, HMM); and the Ocean Alliance (CMA CGM/APL, COSCO/OOCL, Evergreen)]. They have the ability to make decisions more quickly and are much better at tailoring capacity to demand.”

Phases of COVID-19 fallout

Let’s turn to what this means for the second half of the year as new blankings for the third quarter are beginning to be announced. Can you explain how you’ve seen this year evolve?

“I’ve actually seen five different periods. The first is Chinese New Year, which happens every year but not at the same time. It’s the most significant event of the year [in terms of container-shipping demand]. The factories shut down and there is a substantial amount of blank sailings.

“In the second phase, you had the coronavirus impact in China. That had the effect of extending Chinese New Year for a couple of extra weeks, and the effect in the trans-Pacific and Asia-Europe trades was roughly the same [in terms of blank sailings] as another Chinese New Year.

“The third phase was a cool-down period, roughly corresponding with the month of March. A lot of people were interpreting this as, ‘OK, it’s good, we’re going back to normal.’”

We could see this in the California import uptick in early April. It was cargo that was originally scheduled to come over after Chinese New Year but got delayed by the coronavirus lockdown in Wuhan. It was catch-up cargo coming over on a time lag.

“Exactly. And this was basically the calm before the storm, which is the fourth period, which is what we’re in now. This is the impact on demand from the lockdowns. So far, the effect of this [in terms of announced blank sailings, including those for future weeks] is the rough equivalent of another two Chinese New Years. So, we’ve basically had four Chinese New Years already in one year.”

Economic fallout phase

Which brings us to what you would call the fifth phase: the effect on demand from the economic consequences of the crisis from unemployment, business failures, the loss of spending power — especially as stimulus checks run out — the drop in government spending due to budget shortfalls, and the ongoing impacts to huge swaths of the economy, from apparel to travel.

“Right, and we don’t believe this will be a V-shaped recovery. If there’s going to be a recovery, we hope it will be in 2021. We think the effect on [container] demand will be somewhere between what we saw in 2001 and what we saw in 2009. We are somewhat bearish on the rest of the year in terms of volume. We’re pretty certain there will be more blank sailings.”

On a positive note, we’re seeing at least some green shoots in the trans-Pacific market. There have been some blanked sailings that have been “unblanked”; there have been some “extra loaders” (added sailings); and there’s a new service from Zim. Also, it’s already the first week of June, so you would expect there to have been more blank-sailing announcements for July by now. The thinking is: Maybe July cancellations will be 10-15%, down from the 20% level seen in May and June.

“It’s reasonable to assume that July will not be as bad as June. That’s also the sense we’re getting from carriers when we talk to them, which of course we do quite regularly, although we don’t know how much of that is them trying to talk up the market.

“You could interpret it two ways: Either the number of blank sailings is coming down as things are getting back to normal and economies are opening up again, or the carriers have just not announced the blank sailings yet and they will be coming. Nobody knows what the effect [of the coronavirus crisis] will be in the medium and long term. Anyone claiming to know with certainty where this will go has merely proven how little they know.”

Can carriers maintain pricing?

The challenge for carriers is whether they can continue to hold the line on freight rates during the economic-fallout phase. If the recovery is more rapid than predicted, you could have one or more of the alliances opting to either not cancel sailings in the first place or unblank more sailings, which would put too much ship capacity in the market, which would depress rates.

“This is what we thought was happening at first when we saw the Ocean Alliance blanking less capacity than 2M and THE Alliance, but it turned out that the Ocean Alliance ultimately blanked about the same share of capacity as the others [but announced cancellations later]. I think that right now, everybody is so terrified of the whole market collapsing that I don’t believe it will happen. On the other hand, carriers have an uncanny ability to grasp failure from the jaws of victory.”

Another rate risk is that if the economic fallout accelerates and cargo demand sinks further, one or more of the alliances could break down and opt for market share over price.

“Well, that’s how it has always been, so there is an argument for it happening again.”

Yet another scenario is for economic fallout to remain bad or significantly worsen, and for alliances to continue to hold the line on prices. This implies more blank sailings and more problems and complications for the shippers of containerized cargo during the second half.

“Shippers have always said, ‘You carriers are cutting capacity because if not, freight rates will drop below your operating costs and you can’t offer the same services and you might go bankrupt. But why don’t you just stop offering those stupid, low prices? There’s no gun to your head.’ Well, there is a gun to their head because to sail a vessel you need to fill it with as much cargo as you can to try to stem the losses.

“Today, carriers are much better at tailoring capacity to available demand, but that’s a double-sided coin. The ability to better tailor capacity means, of course, that disruptions for shippers due to blank sailings are on the increase. And unfortunately, there’s no easy solution to this.” Click for more FreightWaves/American Shipper articles by Greg Miller