There are companies that spend tens of millions of dollars and deploy vast amounts of computer power to track the world’s tanker fleet, using automation and scalability to distill intelligence from ship movements.

And then there’s TankerTrackers.com, which has garnered more headlines than all the rest.

TankerTrackers.com is the antithesis of scalability – a small team of amateur sleuths, more Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew than HAL 9000, more likely to be hunched in the dark trying to identify a single ship’s telltale features on an ultra-magnified satellite image than crunching numbers.

TankerTrackers.com co-founder Samir Madani began following ship movements as a hobby. He was also one of the co-creators of the twitter community #OOTT, the Organization of Oil Trading Tweeters. The hobby transformed into a fully incorporated commercial enterprise in 2018, with Madani going full time, together with co-founders Lisa Ward and Breki Tomasson.

The timing was impeccable. In the two years since, U.S. sanctions have increasingly targeted crude tankers, the tanker industry has become a major focus of stock investors, and oil has become an ever-more-important fulcrum of geopolitics and the global economy.

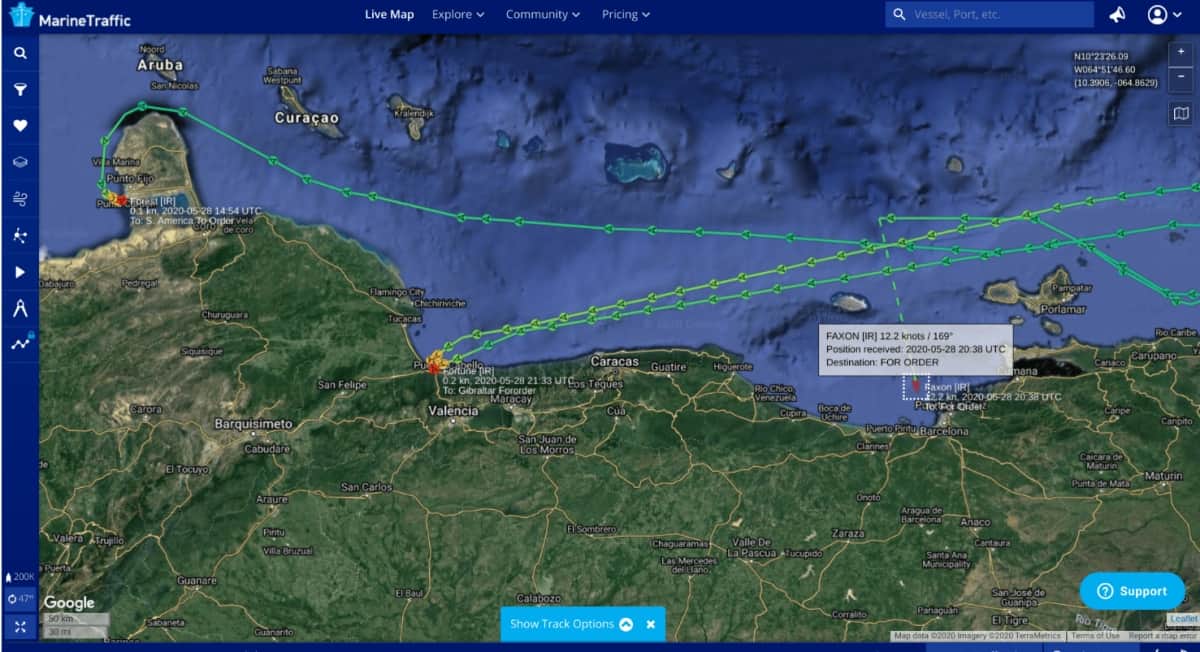

“We didn’t go for the 1%. We went for the 99%,” said Madani of the retail-focused business model. The company uses Automatic Identification Service (AIS) data on ship locations and drafts (the distance between the waterline and the hull bottom) from MarineTraffic.com; satellite imagery from Planet Labs; and sells subscription analytical research – including country export and floating storage reports – at a price of under a dollar a day.

Madani, who lives in Stockholm, spoke at length with FreightWaves on Thursday, detailing how his company shines a light on events that some governments and businesses want kept dark, and the reason, beyond profit, why he believes this is so important. The following is an edited version of that conversation.

Venezuelan and Iranian oil to China

FreightWaves: The focus on sanctions has never been higher among shipowners and investors, with the new attention on Venezuelan crude exports to China layered on top of the pre-existing focus on Iranian exports to China. Venezuelan and Iranian oil goes to China in two legs, switching tankers via ship-to-ship (STS) transfers in Asian waters to obscure the evidence trail. You’re tracking these STS operations?

Madani: “Definitely. Over the past year China has been reporting that it’s taking far less Venezuelan and Iranian oil, but we can see how the system works. The Venezuelan oil arrives after STS transfers in the Strait of Malacca and it gets imported as a Malay blend. It looks like the graphs for [Chinese imports of] Venezuelan and Iranian oil are going down and the graph for Malaysian oil is skyrocketing out of nowhere, as if Malaysia is shipping more oil to China that it produces at home.

“We can see the Venezuelan crude arrive by STS transfer – it’s very transparent, but the Iranian ships turn their [AIS] transponders off.

“Last year, they were very sloppy about it. The Iranian vessel would be in the ‘digital darkness’ but the other ship [that received the cargo] would, all of a sudden, have a magical draft change in the ocean, and when you zoomed in on those coordinates [with satellite imagery], you’d also see the Iranian vessel.”

“Now, they’ve improved their game. Both ships switch off their transponders. We need to use other means to spot them. We do have other tools, which I can’t talk about.”

How do you identify an STS transfer when you have at least one of the two ships’ AIS transmissions?

“Part of the AIS transmission is draft changes [as a ship fills with cargo, draft increases; as it unloads cargo, draft decreases]. When oil is discharged at a port, there’s a draft change. MarineTraffic has STS alerts, which detect when two AIS transponders are close enough [at sea or anchorage]. If there is an STS transfer there will also be draft changes. If there’s an STS alert but I don’t see an AIS update on draft levels, we go in with satellite imagery and study the shadows. When the cargo is being removed and a ship is higher above sea level, the shadow will extend further.”

You must spend a lot of your time looking very closely at magnified satellite images.

“I sit in the dark in my basement zooming in and playing with filters. Clouds can get in the way but if you have a trained eye and you know what to look for, even a small detail can tell you what kind of vessel it is.

“In 2018, when Iran started to switch its transponders off [due to sanctions], we underwent a massive operation here at TankerTrackers.com and logged the visual characteristics of every single vessel that went to Iran. We have multiple images of each in our database, so if a vessel pops up now [with no AIS signal], we’ll be able to tell you exactly which one it is.”

Multiple data sources

There are a lot of companies that track ships with AIS data, but you clearly use AIS very much together with satellite and other data sources. That makes a lot of sense because there are both unintentional inaccuracies with AIS data, such as system glitches, and intentional inaccuracies, due to deception and security precautions.

“We use every tool in the shed. Our policy is to have at least two data points; I cannot rely on only one. And there has been a big improvement in resolution of satellite imagery and the cost has come down tremendously.

“There is ‘spoofing’ of AIS locations, where there is false positioning – it’s just like you see on Snapchat, where people are posing to be in one location and they’re actually not.

“There is also AIS manipulation. There was a case, and I’m not kidding, where they put the AIS transponder of an Iranian VLCC [very large crude carrier; a tanker with capacity to carry 2 million barrels of crude oil] on a tugboat and had it sail around the Gulf of Aden. The tug was called the Iron Man and it was carrying the transponder of an Iranian VLCC called the Diamond II. The imagery shows you a tugboat right where a VLCC supertanker is supposed to be.”

Breaking news

Tankertrackers.com has garnered widespread attention after breaking a number of major stories, most recently the five Iranian tankers full of gasoline headed to Venezuela, and last year, the case of the Iranian VLCC Grace 1, renamed Adrian Darian 1, bringing oil to Syria after it was detained in Gibraltar. How did those stories develop?

“We primarily track crude and gas condensates; that’s our bread and butter. We discovered the Iranian [product] tankers going to Venezuela by accident. What happened was that I clicked on the MarineTraffic filters in the wrong order, clicking flags first, and it showed me these Iranian-flag vessels in the Med and I wondered: Why are they heading west? It’s not like they’re going to Rotterdam. Then I saw the destination [listed in the AIS data] for one of them as Caracas and I understood.

“This was hush-hush between the two governments and we felt it was our responsibility to break the story and let the Venezuelans understand what was going on from a neutral party. The Venezuelans have been paying more than a month’s salary for a single liter of gasoline and this let them know that cheap gasoline was on the way.

“With the Adrian Darya 1, we saw it doing the craziest thing – after loading at Kharg Island [Iran], it was sailing all the way around Africa. We immediately understood why that made perfect sense. It was going to Syria.

“Normally we’d see three Suezmaxes [tankers that carry 1 million barrels of crude oil] a month going from Iran to Syria via the Suez Canal. Egypt will not stop an Iranian-flagged ship from using the canal. That would be illegal under the Convention of Constantinople. Egypt will only do something if a country is at war with Egypt.

“But a fully laden VLCC can’t go through the Suez because the canal is too shallow. It has to unload half of its cargo at the Sumed pipeline first – and that pipeline is partly owned by countries within the GCC [Gulf Cooperation Council] that are opponents of Iran.

“[The VLCC] stopped in Gibraltar for supplies because it didn’t think there would be a problem. Iran had no issues with the U.K. and at the time the ship was Panamanian-flagged and called the Grace 1. Then the U.S. put pressure on the U.K., the U.K. reacted and the vessel was arrested. After it was released, it immediately changed its flag to Iran and changed its name.

“They said the ship was going to deliver to customers in the Med but it went to Syria – where we’d said it would go all along. It switched off its transponder but we were covering it every step of the way. We saw that it looked like it was making a delivery to a tanker called the Jasmine, and we said that we were waiting for confirmation that an STS had taken place. Then [U.S. Secretary of State] Mike Pompeo took our tweet and our satellite photo and our text with our name on it and made his own conclusions. We weren’t happy about that and voiced our concerns with the State Department about our name being used that way.”

The bigger picture

Given all geopolitical tensions and sanctions, and the importance of crude oil, there’s likely to be continued focus in the press on what TankerTrackers.com is uncovering. How are you handling that?

“We realize we can’t control the narrative. It doesn’t work that way. It’s a balancing act between taking care of our own house, in terms of our own subscribers, and how we break news internationally – because we are making massive discoveries all the time.

“I don’t want our brand weaponized for geopolitical reasons. I’m actually turning down a lot of interviews because a lot of media organizations, especially in the Middle East, want to use us against their adversaries. So, I stick mostly to the financial news channels – I’m frequently on CNBC and Bloomberg – and anything within maritime, of course.

“We do want to be continuously engaged with the press and work on stories that matter and try to show the world and the audience that things are not as black and white and as simple as they thought. We’re putting a lot of light on the grey area – the very large sea of gray between the two polar caps.

“I think this is very important. I grew up in the Middle East and saw all of this stuff firsthand. I’m half-Arab, half-Croat. I’ve seen those wars in the East Med, and I believe trade is the solution to peace in the Middle East. When two countries are in some kind of diplomatic spat but oil continues to flow between them, there is no conflict.

“Why should they be forced to sit at a table and sign something they’re not ready to commit to? A business contract is different. It’s a commitment that ties people to their names, to their reputations. This region understands trade. They’ve been trading with each other for thousands of years.” Click for more FreightWaves/American Shipper articles by Greg Miller