It was a classic venture capital bubble: Entrepreneurs dreamed big and aggressively expanded into a still-developing market; huge sums of cash were raised by finance bros from investors unfamiliar with the industry; government regulations were non-existent, modified by friendly politicians or ignored; the abundance of easy money outstripped the number of good ideas in the space; capacity was overbuilt well ahead of demand; and dozens and dozens of bankruptcies followed, leaving bondholders with a bag of worthless IOUs.

This is J.P. Hampstead, co-host of the Bring It Home podcast with Craig Fuller. Welcome to the fourth edition of our newsletter. I’m not writing today about ride-share apps, e-commerce pet food stores or robotic pizza delivery, but about railroads in the second half of the 19th century.

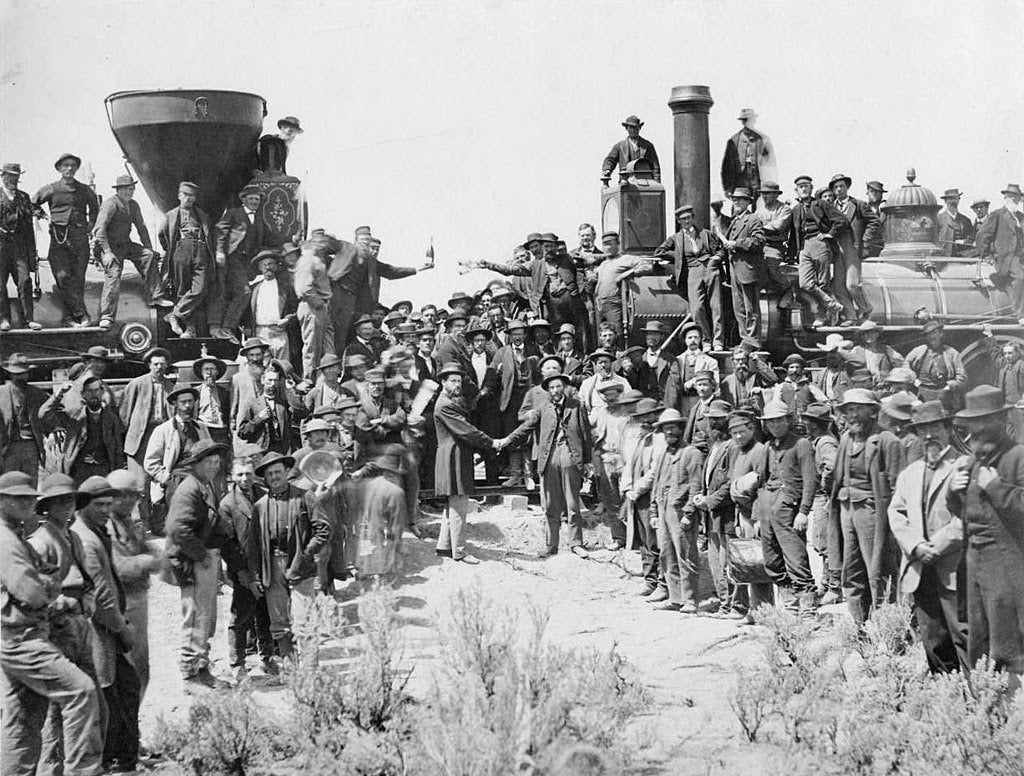

(Photo: Andrew J. Russell)

After the Civil War, during which more railroad mileage was destroyed through lack of maintenance and deliberate sabotage than was newly constructed, the railroad industry was set up for a boom. The Transcontinental Railroad, which linked the Central Pacific to the Union Pacific, was completed on May 10, 1869, and served as an emblem of a new age of American unity. Financier Jay Cooke, who had sold $500 million worth of Union war bonds in 1862 and an additional $830 million in 1865, turned to slinging bonds for the railroads, raising $100 million in 30-year bonds with a 7.3% coupon for the Northern Pacific by 1871.

In fact, so voracious was the railroads’ appetite for capital, that the industry “co-evolved” with Wall Street, consolidating financial power among the big banks of New York, which supplanted Boston, which had funded the whaling industry, as America’s financial center.

The massive sums spent on infrastructure — and the generous government concessions granting land easements and subsidizing the railroads’ cost of capital — were ambitious, speculative and perhaps ahead of their time. Prominent historian at Stanford University (named for Leland Stanford, founding president of Central Pacific Railroad) Richard White argued that the transcontinental railroads, at least in their early decades, were unnecessary and wasteful get-rich-quick schemes that suffered from insufficient volume and overcompetition for nearly half a century after their construction.

“The transcontinentals were the means to something beyond themselves even if there was a certain lack of clarity about what those things might be,” White wrote in “Railroaded: The Transcontinentals and the Making of Modern America.” “They were more than business propositions. They were, like the Civil War, exercises in nation building, but whereas the Civil War settled the question of the national authority of the central state and sutured together the North and the South, the transcontinentals opened the question of a national market and the relation of the East and the West.”

The challenges and opportunities inherent in the railroads of the 19th century are in many cases the same that the U.S. faces today as it considers crafting an industrial policy for the 21st century. How does the government fairly pick winners and losers, given the influence of powerful lobbyists? What degree of regulation, guidance and risk best serves the public interest? Which fortunes will be made (or lost) in the mad dash to build as hundreds of billions of dollars of federal and private investment is unlocked?

Although the transcontinentals and broader railroad industry was a landscape littered with fraud, corruption, bribery and bankruptcy, the lasting effects of America’s freight rail network were positive. Wall Street consolidated early around the railroad industry, but so did steel, coal and agriculture. The sheer volume of silver and grain exported from America’s heartland in the decade following the completion of the transcontinentals was enough to crash global commodity prices. Meanwhile, millions of people poured into the middle of the country on railroads, even if there were barely any towns for them to live in.

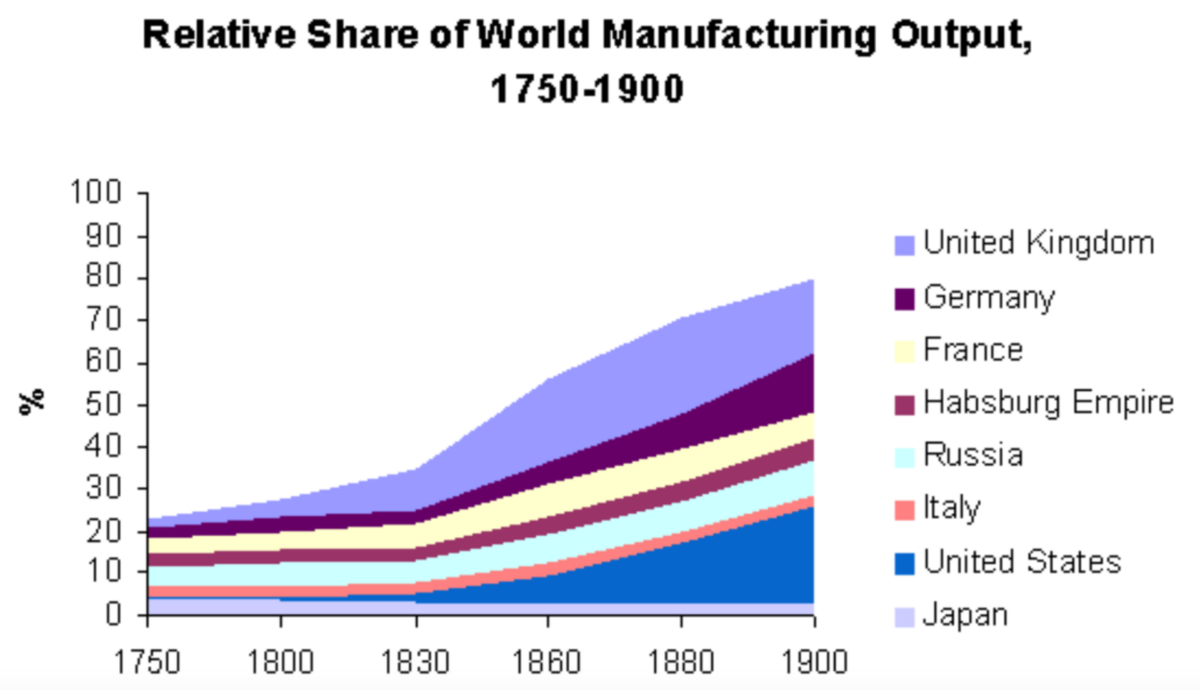

The early railroads may have been too big to succeed. But they formed the pipelines for the freight — the raw materials — that powered America’s ascent to global leadership in manufacturing output and tied disparate cities across a far-flung region into a single market.

That brings me to what might be the most important question about our contemporary reindustrialization: How will the trillions of dollars being invested today make life radically different a generation from now, in ways that are completely unexpected?

Quotable

“We shipped $2.9 billion of AI servers in Q3, resulting in an AI server backlog of $4.5 billion. Our five quarter pipeline grew more than 50% sequentially with growth across all customer types. We continue to gain traction with Enterprise customers, large and small, with over 2,000 unique Enterprise customers since launch.”

– Jeff Clarke, vice chairman and COO of Dell Technologies, on its Q3 earnings call, Nov. 26, 2024

Infographic

News from around the web

U.S. solar module and cell manufacturing investments in November

Silfab Solar closed on $100 million of new financing to scale its solar cell manufacturing plant – a $50 million equity and a $50 million senior secured led by Breakwall Capital. As Toyo Co. looks to better serve the U.S. solar market, the company has agreed to acquire 100% of membership interests in Solar Plus Technology Texas LLC located in the Houston metropolitan area, via its subsidiary Toyo Solar LLC. Trina Solar and Freyr Battery announced an agreement for Freyr to acquire the U.S. solar manufacturing assets of Trina Solar, specifically the 5-gigawatt, 1.35 million-square-foot solar module manufacturing facility in Wilmer, Texas, that started production on Nov. 1. The facility is expected to ramp up to full production in 2025 with 30% of estimated production volumes backed by firm offtake contracts with U.S. customers.

US manufacturing contraction slows in November, outlook uncertain

U.S. manufacturing contracted at a moderate pace in November, with orders growing for the first time in eight months and factories facing significantly lower prices for inputs.

The improvement reported by the Institute for Supply Management on Monday tracked similar increases in other sentiment surveys, which have risen on hopes of more business-friendly policies from the incoming Trump administration.

US issues new restrictions on chip manufacturing exports to China

The Biden administration issued new restrictions Monday on exports of certain semiconductor chips and equipment to China, marking the administration’s latest crackdown to curb the country’s competitive advancements in chipmaking. The new export controls place more than 100 Chinese chipmaking tool manufacturers on a restricted trade list, prohibiting U.S. companies from sending them equipment without specific permission, the Commerce Department’s Bureau of Industry and Security said Monday.

Explainer: After China’s mineral export ban, how else could it respond to U.S. chip curbs?

China has banned exports to the U.S. of some goods containing critical minerals while tightening exports on others, after U.S. curbs a day earlier on the Chinese chip industry.

Following is background on export controls and other steps that analysts say Chinese authorities might take to safeguard China and its companies’ interests.

On Tuesday, China banned exports to the U.S. of items related to gallium, germanium, antimony and superhard materials, the latest escalation of trade tensions between the countries ahead of President-elect Donald Trump’s taking office.