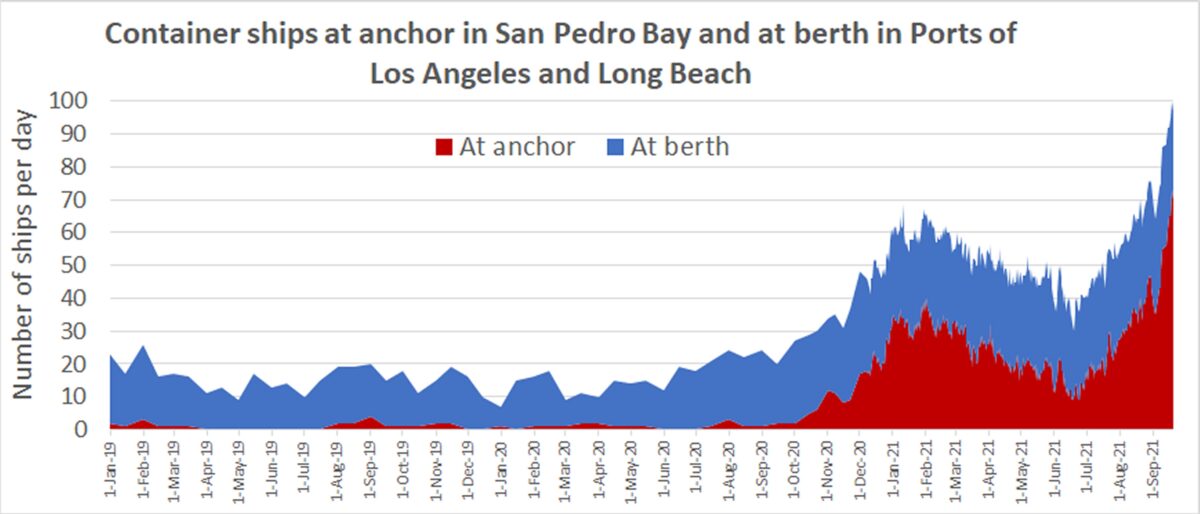

The number of container ships at anchor or drifting in San Pedro Bay off the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach has blown through all previous records.

The latest peak: There were an all-time-high 73 container ships in the queue in San Pedro Bay on Sunday, according to the Marine Exchange of Southern California (the tally inched back to 69 on Tuesday). Of the ships offshore Sunday, 36 were forced to drift because anchorages were full.

Theoretically, the numbers — already surreally high — could go even higher than this. While designated anchorages are limited, the space for ships to safely drift offshore is not.

“There’s lots of ocean for drifting — there’s no limit,” Capt. Kip Loutit, executive director of the Marine Exchange of Southern California, told American Shipper.

“Our usual VTS [Vessel Traffic Service] area is a 25-mile radius from Point Fermin by the entrance to Los Angeles, which gives a 50-mile diameter to drift ships. We could easily expand to a 40-mile radius, because we track them within that radius for air-quality reasons. That would give us an 80-mile diameter to drift ships,” said Loutit.

Limits on land

The Southern California gateway is acting like the narrow tube on a funnel: Ocean volumes pour in from Asia and can only flow out at a certain velocity due to terminal limitations as well as limitations of warehouses, trucking and rail beyond the terminal. When the flow into the top of the funnel is too great, as it is now, it creates an overflow in the form of ships at anchor or adrift. This offshore ship queue is equivalent to a massive floating warehouse for containerized imports whose size is only limited by liner shipping capacity and U.S. consumer demand.

How constrained is the flow? Port of Los Angeles Executive Director Gene Seroka said during a press conference on Wednesday that container dwell time in the terminal “has reached its peak since the surge began” and is now six days, worsening from 5.3 days last month. On-dock rail dwell time is 11.7 days, not far below the peak of 13.4. Street dwell time (outside the terminal) “is 8.5 days, nearing the all-time high” of 8.8 days, said Seroka. It has worsened from 8.3 days a month ago.

Marine Exchange data reveals the constraints of the Los Angeles/Long Beach port complex. Since congestion began, the total number of container ships either at anchor or at berth has risen and fallen — it was an all-time-high 100 on Sunday, more than five times pre-COVID levels. But one stat has remained remarkably consistent: The number of container ships at Los Angeles/Long Beach berths has remained in a tight band of around 27-31 per day — that is what the land side can handle, the tube of the metaphorical funnel. Throughout 2021, all ship arrivals over that threshold have overflowed into the anchorages and drift areas.

More ships deployed in trans-Pacific

Meanwhile, at the wider open end at the top of the funnel — the drift area radius outside the port — a much higher number of ships is flooding into Southern California than ever before.

Seroka noted that of the 84 ships his port handled in August, 11 were “extra loaders” — ships that are not part of a scheduled service. “And in addition to the extra loaders we’ve seen from incumbent carriers, there are no less than 10 newcomers [new services] to the trade,” he added.

According to Alphaliner, deployed trans-Pacific capacity is up 30% year on year.

Asked by American Shipper whether ports or terminals could proactively stem inbound flows to provide more breathing room, Seroka replied: “Slowing down these ships is something we thought about in the early days of the surge, to try to give us a little bit more time in between to get ready for the next ships. But if you start looking at slowing down these ships, it’s going to back up the vessel supply chain even further and make schedules an even deeper concern for liner companies.” In other words, no.

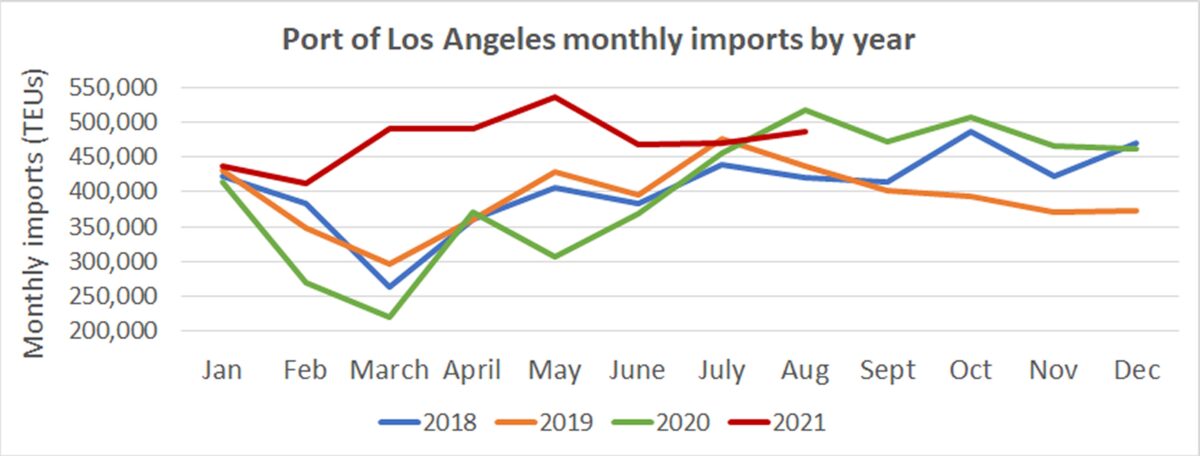

Imports down year on year

The higher the number of ships waiting offshore, the bigger the queue and the longer it takes for a vessel to get a berth. On Tuesday, the average wait time to reach a berth in Los Angeles (30-day rolling average) rose to an all-time high of nine days.

That, in turn, delays imports. Back in August 2020, when import demand surged post-lockdowns, there were almost no ships at anchor off Southern California. This August, there was an average of 36 ships at anchor per day, according to Marine Exchange data. The port of Los Angeles handled 485,672 twenty-foot equivalent units of imports in August — down 5.9% year on year.

As Seroka pointed out, on the last day of August, 26 ships were at anchor waiting for berths in Los Angeles. These ships had 205,000 TEUs of cargo on board, which was pushed into this month (just as delayed cargo from this month will be pushed into October).

Total throughput for the port was 954,377 TEUs in August, down 0.8% year on year due to the decline in imports and a 23% plunge in loaded exports, offset by a 17% surge in outbound empty containers.

The port expects volumes to pull back from August’s level over the next two months, to 930,000 TEUs in September and 950,000 TEUs in October. It expects full-year throughput of 10.8 million TEUs.

More blank sailings ahead

What could stem the tide of cargo arriving in Southern California and cap the size of the floating warehouse?

When congestion peaked earlier this year, in the first quarter, it led to a large number of “blanked” (canceled) sailings in the second quarter. Ships stuck at anchor in San Pedro Bay could not get back to Asia in time, forcing carriers to cancel voyages. Those cancellations helped pare California anchorage totals in May and early June.

Carriers are yet again blanking sailings as a result of escalating congestion in Southern California. But this time, the number of ships at anchor and drifting has much more room to run before the network reaches its limit.

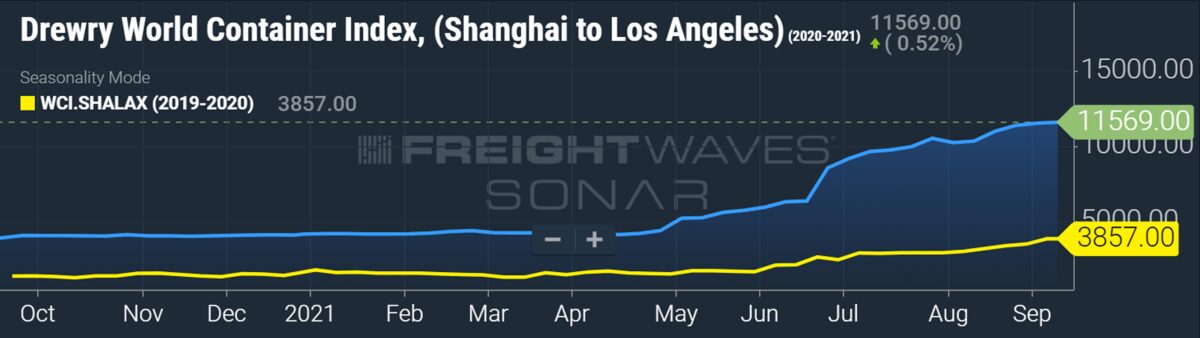

Not only are there more services and extra loaders, but carriers also have an incentive to blank sailings in other markets instead and redeploy ships into the trans-Pacific, where they can earn more money by topping off rates with premium charges.

According to Lars Jensen, CEO of consultancy Vespucci Maritime, “If we continue to see extremely strong demand specifically on the trans-Pacific, carriers may elect to blank a few Asia-Europe sailings and instead temporarily let a few of those vessels make a trip across the Pacific before coming back to Asia and re-phasing into the Asia-Europe network.”

According to Alphaliner, ships are already being pulled from the Asia-Middle East and Asia-Red Sea lanes to make more money elsewhere. Alphaliner reported that up to 50% of Asia-Middle East services are now being blanked because vessels have been redeployed to trades like the trans-Pacific “where spot freight rates are at historic highs.”

Click for more articles by Greg Miller

Related articles:

- Just how many containers of cargo are stuck off California’s coast?

- How high can container shipping profits go? Will 2022 top 2021?

- In the eye of the congestion storm: Q&A with Port of LA’s Gene Seroka

- Shipping chaos gives top importers ‘massive competitive edge’

- Global demand isn’t booming. So why are shipping rates this high?

Lulu

They claim a lot of things however due to having family and knowing so many people including brokers in the business I know the real truth which is California has a great shortage of Trucks to haul the freight due to their ridiculous rules on trucking that most companies don’t fit their criteria to travel into Cali. Ship this stuff to Texas, The Northeastern part of the USA and else where then U will start to see it moving and prices go down to because everything is double the price in California also!

Lulu

They claim a lot of things however due to having family and knowing do many people including brokers in the business I know the real truth which is California has a great shortage of Trucks to haul the freight due to their ridiculous rules on trucking that most companies don’t fit their criteria to travel into Cali. Ship this stuff to Texas, The Northeastern part of the USA and else where then U will start to see it moving and prices go down to because everything is double the price in California also!

Grudgeman

Where are the feds, use military to assist with port backups at their base…

Joe shmoo

Looks like it really is true. China owns our ass.

Don Starr

A big thank you to all the UP and BNSF and PHL railroad workers and the dedicated longshoremen and marine dock clerks for kicking butt and doing a good job. You drayage truck drivers too.

Work hard and make lots of money. 💰

mrbigr504

Yeah right! Everybody is making money but the owner operator container hauler! That’s part the reason so many cans are sitting still. Yeah COVID played a part in it but trust me when I say that if the truckers don’t roll, ain’t nothing moving! I was pulling out of Atlanta and have pulled out of the port of Savannah and it’s just not worth the trouble! Until we get everything out on the table & get these numbers straight, this current 3rd party way doing business is just gonna get worse because there’s just waaaay too much pimp’n going on as it stands! And don’t get me started on how we get stuck paying for cheap’azz Chinese recapped inner tube tires on these raggedy’azz chassis that they wanna pay us $40 & $50 bucks to go get and then don’t pay you to go get the container to complete the set up! Until this system gets an overhaul in the intermodal trucking side of the industry, it’s gonna get worse! Did I mention that some carriers wanna pay a owner operator $50 to $75 bucks more for a hazmat load? Yeah call me when y’all are ready to get serious with the owner operators because the way it’s going now, somebody’s gonna have to “Sh-t or get off the pot” here reeeal soon!

Roger Martinez

“There’s not enough dock workers because of COVID or whatever….” from a VP at Covenant. I hope he was taking the video while on vacation, and not for educational purposes. I’d suggest Freight Waves remove the audio, what a disservice to all the dock workers and longshoreman. “Earlier this year, the Port of Los Angeles, which will release its August data later this week, became the first port in the Western Hemisphere to move 10 million TEUs during a 12-month period.” So not enough dock workers moved more freight than any port in the western hemisphere, EVER. I for one, as an Angelino and transportation worker, truly appreciate our dock workers and the hard work they are doing at our Port. Thank you!!! As for Covenant, they are from Tennessee, and do not operate in our port. Please remove the audio.