Russian warships entered the Red Sea last Thursday, for what the Russian Pacific Fleet’s press service has stated was the performance of “assigned tasks within the framework of the long-range sea campaign.” This intentional vagueness has invited no small amount of speculation as to the ships’ true objectives.

Theories range from retaliatory pressure on Israel, which decided in late February to co-sponsor a United Nations resolution condemning Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, to supporting beleaguered ally Syria’s military objectives in the region.

Then again, the warships might simply be in the Red Sea to guard against attacks from Yemen-backed Houthi rebels.

‘Not to be trusted’

In late March, Bloomberg reported that the Houthis had promised safe passage to Russian and Chinese vessels in the Red Sea and nearby Gulf of Aden. In exchange, the two countries allegedly agreed to leverage their position as members of the U.N. Security Council to support the Houthis.

Two days after this report, however, Houthi militants fired five missiles at a Chinese-owned oil tanker, causing a fire but minimal damage and no injuries.

Lars Jensen, CEO of Vespucci Maritime and industry analyst, wrote in a post on LinkedIn that the Houthis might have attacked by mistake, believing the ship to be British-owned: “It would for now appear that Houthies [sic] have acted on outdated information and in the process clearly demonstrated that even if there was potentially a deal to grant safe passage, such a deal is not to be trusted.”

If China and Russia find the Houthi problem as intractable as the U.S. and its allies have, it would all but halt what little maritime traffic remains in the region.

Danish shipping giant Maersk, in a late-March update, reaffirmed its commitment to avoiding the Red Sea for the foreseeable future. Maersk cited attacks on the True Confidence — which claimed three lives and marked the Houthis’ first fatalities caused on a commercial vessel — and the Rubymar, the first vessel lost to a Houthi assault.

Scarce motion in the ocean

Despite the unexpected length of the Red Sea crisis, it is not likely to hold spot rates captive for a similar amount of time. Shipping lines have more than enough capacity to accommodate reroutes along Africa’s Cape of Good Hope, having hit shipbuilders with a tsunami of orders during the COVID boom.

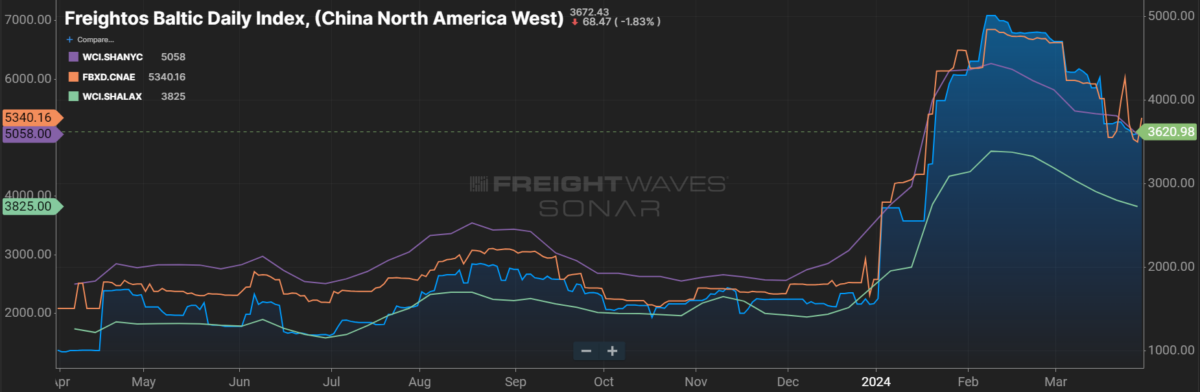

The greatest evidence for geopolitical risk’s limited ability to translate to higher spot rates is seen in lanes from China to the Mediterranean. After the Chinese oil tanker was struck in late March, rates along these lanes unsurprisingly spiked and have held at a plateau since.

Moreover, transit times from China to Spain — host to some of the busiest ports in the Mediterranean — have increased by three days since the start of the year, while vessels face average delays of 12.6 days at both origin and destination. As recently as December, such delays averaged less than a single day.

Yet these rates’ highs are unable to match those of early-to-mid-February, when China was preparing to shut down operations in advance of its Lunar New Year celebrations. And while rates might hold at their current level for a few days or weeks, there is little cause for them to rise further. Rather, rates will likely trend downward as they had for most of March.

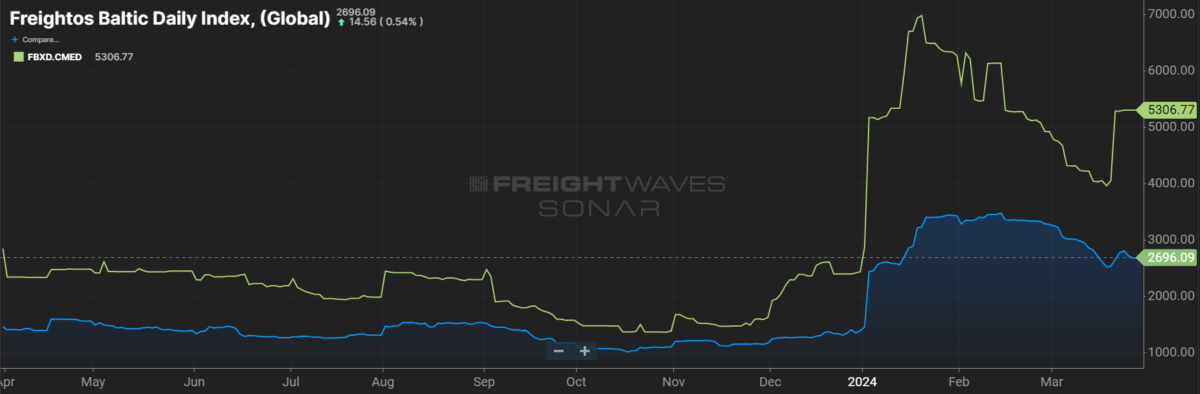

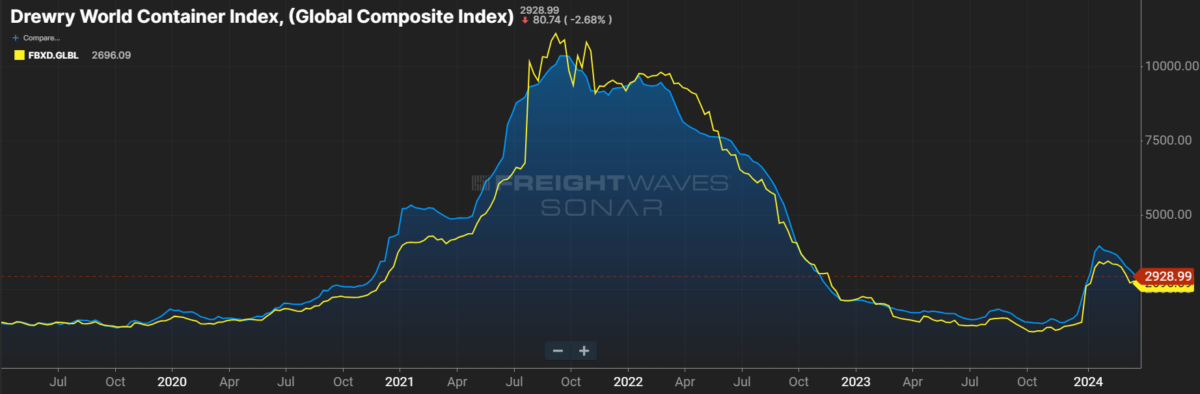

Such is an examination of lanes most impacted by the Houthis’ recent attacks, which proved to be little more than a drop in the bucket for rates on a global scale. The global composite of the Freightos Baltic Daily Index, which tracks spot container freight rates across 13 lanes, is actually down 17.2% since the start of March. Similarly, Drewry’s World Container Index — which tracks both spot and short-term contract freight rates — has fallen 16.2% over the past four weeks.

Of course, there is also the domestic matter of the Port of Baltimore, now closed indefinitely after the collapse of the nearby Francis Scott Key Bridge. While this closure is estimated to have a limited impact on the region’s intermodal market, it will rattle the supply chain of automobiles.

Markets were still quick to react, however, as spot rates from China to the U.S. East Coast jumped 6.7% from where they were a week prior to the incident.