NEW YORK — The chairman of the federal Surface Transportation Board got up Wednesday in front of a room full of railroad executives, analysts and customers and ripped the industry to shreds.

At the RailTrends conference sponsored by Progressive Railroading, after hearing presentations on the first day and into the second day about the need for growth, Martin Oberman offered his verdict on why that growth isn’t there: The industry cut too many workers and now is desperately trying to hire more.

“I’ve heard from shippers that they have traffic to offer them and they can’t get a salesperson on the phone,” Oberman said during a post-speech question-and-answer period.

The STB is the chief regulator of business activity on the railroads. It is an independent agency, unlike the Federal Railway Administration, which is part of the Department of Transportation.

Right from the start of his address, Oberman referred to the “Class I service meltdown,” which he then referred to as a “service crisis.” The service issues led to STB hearings on them last spring.

He said it had been “brewing long before the pandemic, but it really came to a head” during the COVID crisis “and it is not close to being resolved.”

Oberman also got specific: The problems are coming out of “the big four” — Union Pacific (NYSE: UNP), BNSF (owned by Berkshire Hathaway (NYSE: BRK.A), Norfolk Southern (NYSE: NSC) and CSX (NYSE: CSX). The other Class I railroads in North America — CN (NYSE: CNI), Canadian Pacific (NYSE: CP) and Kansas City Southern, which is now part of CP but is awaiting final approval from the STB for the merger to be complete — “have not presented anywhere near these kinds of problems,” he said.

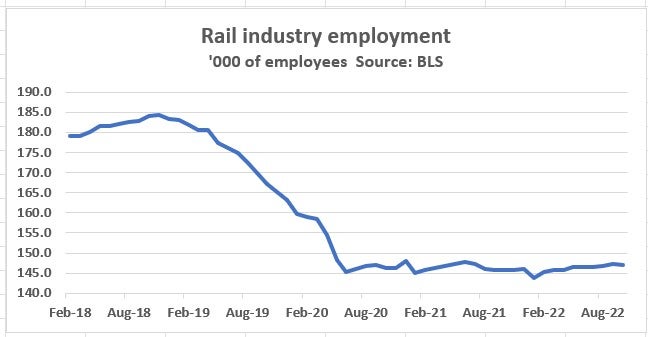

Oberman referred to estimates by the Association of American Railroads that a strike or lockout of railway workers, which remains a possibility as ratification of a September labor agreement continues, would cost the U.S. economy $2 billion per day. But he said the industry itself had implemented what amounts to a “partial lockout” by reducing their workforces more than 10% since the start of the pandemic.

And it didn’t just begin with the pandemic, Oberman said. Between January 2016 and February 2020, Class I railroads reduced their workforces by 29,000 workers, according to STB data cited by Oberman.

With that reduction, Oberman said, “the railroads have lost most if not all of their cushion and resilience to respond to the inevitable disruptions.”

After citing those numbers, Oberman came to the heart of his issue with the railroads’ business practices in recent years. “When railroads try to excuse their failures by pointing to labor shortages at other businesses, those other businesses did not enter the pandemic having stripped themselves of nearly 20% of the workforce in recent years,” he said.

Oberman also said that some major rail users, like grain producers, “made the very difficult decision to play the long game and keep their employees even if it meant a temporary hit to their profit.”

“Very profitable railroads made the opposite decision to the detriment of their network,” Oberman said.

He cited other numbers that measure declines in the size of the workforce, “and I have a hard time distinguishing this behavior from what is effectively locking out 10% of their employees,” Oberman added, coming back to the comparison of employee reductions and a partial industry lockout that he believes effectively already has occurred due to the drop in workforce size.

The result, Oberman said, is that by the middle of 2021, Class I railroads “were falling further behind in the quantity and quality of their service.” That service “really fell off the cliff” in the fourth quarter of 2021 and the first quarter of 2022, he said.

“It is beyond question that the service problems were the result of intentional drops in the workforce,” Oberman said.

Railroads now are facing “huge hurdles” in trying to find new workers. And the result of the cutback is “not abstract. It is felt by customers every day,” he said.

Oberman cited specific losses in economic productivity as a result of the embargoes. One customer needed to euthanize “millions” of chickens because it couldn’t get them to market, and ethanol plants reported to the STB numerous short-term shutdowns because there were no railcars to get product to market.

“How much has this country lost by the decision to implement a 10% work stoppage?” Oberman asked.

One result of the cutbacks, according to Oberman, is that embargoes are being used with more regularity. They are now “routine,” he said, citing Class I embargo totals of 140 in 2019, rising to 631 last year and already up to 1,115 embargoes this year.

“They’re usually tied to congestion but they really are a euphemism for ‘we don’t have enough crews,’” Oberman said.

The message at the overall RailTrends meeting this year was growth. It was the message last year too.

Oberman took notice. “Last year all we heard about was a pivot to growth,” he said. “Has there been any growth? It is not growth. It is continuing decline.”

He took a populist tone at times, referring to “highly paid CEOs” as one of them, Tracy Robinson of CN, sat near the front after having given her own address on the need for growth.

He said the cost cutting through employee dismissals saved less than $5 billion in payroll costs while Class I railroads were returning nearly 12 times that to shareholders in buybacks and dividends. Reducing those payouts by the roughly $5 billion in cost savings through the payroll paring “would have been a drop in the bucket,” Oberman said.

“Today the railroads tell us they are still having a hard time recruiting and retaining workers and try to blame this on the ‘Great Resignation,’” Oberman said. “The fact is the railroad’s personnel practices made these jobs much less desirable.”

More articles by John Kingston

CP CEO: KCS merger opens up Lazaro port as Pacific alternative

Railroad’s endless pursuit of market share highlighted at key conference

Tired Rail

Who’s essential now? Never heard Rail workers being essential through the pandemic , but guess we are now. We didn’t get bonuses for working and the monster trains we haul and the lack of man power is a joke. a they should sleep in a dorm stuck there hours, that’s what should be mandated. They should be on call and tired and fed up. Enough is enough. Everyone worried about holiday time and we don’t even get a holiday off. Walk a week in my boots and you’ll sing a different tune.

Karen

I wish up would get their s*** together. I don’t work for the railroad itself I’m a taxi driver basically for crew members and the last 3 months have been the slowest in the 4 years I’ve been doing this I haven’t even made $200 a week. I hear complaints from all the crew members and it’s pissing me off that up is cowtowing to lining the CEOs and shareholders pockets and they don’t give a damn about the people who are actually keeping them in business, their employees and the people that contract with them.

Jeremy King

Do more with less . Thats what my employer likes to do. I feel like I’m breaking down my body twice as fast as I should be . I’ve been doing my job, then when I’m done I’m running another machine because we can’t fill the jobs we have in Track Department. My doctor tells me I won’t be able to walk when I retire at 60 unless I make a change ! Its a sad time in the rail industry.

Rob

@modernrail, we work roughly 36 hours because we are locked in a hotel for upwards of 46 hours waiting on our call to finally go home which by the way IS NOT PAID TIME AWAY FROM HOME. don’t judge but what you think you know. Talk to railroaders and find out why…