Diamond S Shipping (NYSE: DSSI) capped a blockbuster run of tanker earnings with an announcement of huge profits and a record quarter, just like the other four listed owners reporting this week.

But the Diamond S conference call on Friday was not a predictable sequel to calls with analysts the days before. The mood was less uplifting and self-serving, more foreboding and straight-shooting.

Diamond S CEO Craig Stevenson and his CFO Kevin Kilcullen did not mince words about the trouble they see ahead — as soon as the third quarter, earlier than implied by tanker executives on prior calls.

Focus on caution

Stevenson is veteran of the tanker industry and the former CEO of OMI Corporation, the company that famously sold its entire fleet in 2007 for $2.2 billion at the very peak of the boom, leaving buyers Teekay Corporation (NYSE: TK) and Torm (NASAQ: TRMD) holding the bag when the financial crisis struck.

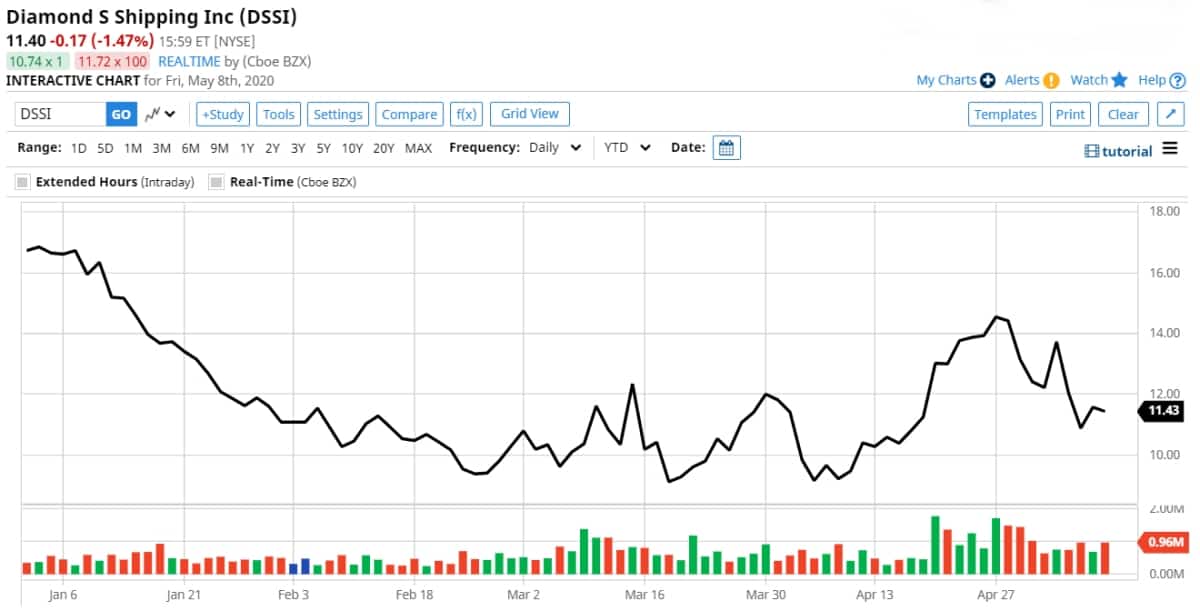

Diamond S, which owns a fleet of 50 product tankers and 16 crude tankers, initiated a $50 million stock buyback program on March 4 only to quickly stop buying after spending just $1.4 million.

“Right when we started our buyback, it got increasingly opaque,” recalled Stevenson. “If you just focus on the rest of the second quarter, everyone feels good about it. But what do the third and fourth quarters really look like?

“You’ve got all these ships in floating storage but we don’t have a strong point of view about how that unwinds. It could be not so bad. It could be much worse.

“So, we stopped purchasing shares,” said Stevenson. “It’s still an incredibly attractive price [on the shares], but you just need to be sure that you can weather the storm. … We clearly expect some challenges in 2020 as the tanker market begins to feel the impacts [of the coronavirus] on the overall macroeconomic environment.”

“We’re still very much believers in the long-term tanker story, but we can see a trough coming with record inventories and demand destruction,” said Kilcullen. “There will be a trough in earnings sometime in the future. How long it lasts and how bad it gets is probably the billion-dollar question for our industry.

“Shipping usually gets into trouble because cycles are unpredictable and the industry does not see it turning into a prolonged downturn or a sharp downturn until it’s already in the midst of it,” he continued, noting that the difference this time around is “the trough is very, very visible.”

Chartering prospects

Diamond S Shipping reported net income of $45 million for the first quarter of 2020, compared to a net loss of $1 million in the same period last year. Earnings per share of $1.13 came in well above the analyst consensus forecast of 85 cents a share.

Comments on the call pointed to two charter-related negatives with wider industry implications.

First, voyage delays due to oil-market disruptions are viewed as a positive for freight rates because they effectively reduce vessel supply, but they’re a negative for companies with vessels caught up in those delays.

Diamond S is one of them. Of its 16 Suezmaxes (tankers that carry 1 million barrels of crude oil), 13 are in the spot market. The spot Suezmaxes have booked 54% of available second-quarter days at $48,700 per day, below expectations.

The reason for the underperformance: five of those Suezmaxes are on so-called “stranded voyages.” Kilcullen explained that these were spot voyages booked in February and March at lower-than-current rates that were supposed to discharge in March and April “but have been unable to do so because of logistical constraints, including refinery closures and lack of onshore storage.”

The charterer pays for a specified period under a spot contract; if the ship is returned late, the charterer pays a separately negotiated daily “demurrage” charge that’s lower than the implied daily voyage rate.

In one example, a Diamond S-owned Suezmax was booked for a five-day job to “lighter” (ship-to-ship transfer to unload) a very large crude carrier (VLCC; a tanker that carries 2 million barrels of crude) off the U.S. West Coast. The refinery shut down before the Suezmax could discharge. The ship is finally offloading that cargo next week after being stranded for one and a half months.

“We’ve been earning demurrage on these stranded voyages, which unfortunately for us is significantly lower than the rates that have prevailed for most of the quarter and we have been unable to fix these vessels to take advantage of the strong market conditions,” said Kilcullen. He disclosed that charterers of the company’s stranded ships have been paying an average demurrage rate of $33,000 per day.

Another chartering issue raised on the Diamond S conference call involved time-charter coverage. In a typical shipping cycle, as spot rates rise toward above-average levels, charterers seek long-term time-charter coverage to cap future transport costs. Shipowners also become more amenable to putting some vessels away on time charters, even if it means losing out on spot upside, as insurance against a sudden rate slump.

Tanker companies reporting this week did indeed announce heightened charter coverage, as would be expected given record spot rates over recent months. The question, however, is whether they can lock in enough time-charter coverage before an extended spot-rate slide.

In the current cycle, the future rate trough — which will come about when floating storage is unwound — is clearly visible, even if exact timing is unknown. This visibility makes charterers less likely to agree to charters of a year or more in duration at rates acceptable to vessel owners, because charterers expect future spot rates to fall.

Diamond S typically has 80% spot coverage, 20% time-charter coverage. “We’ve brought that [time-charter coverage] closer to 30% in light of the world we’re living in today — the third and fourth quarter is going to be exciting times,” said Stevenson.

“We’d certainly look at more long-term charters,” he added. “But the vast majority of time charters are for six months. The customers see the same thing that we’re talking about.”

Floating storage

As an owner of both crude and product tankers, Diamond S has a broad view on floating storage.

“Both crude and products [tanker markets] have tightened as a result of floating storage,” said Stevenson. “You normally see a contango [floating storage] market in the large crude oil tankers, but the contango market is alive and well in products in a giant way, even on smaller 50,000-tonner MRs [medium-range product tankers]. We’re in pretty unusual territory. How many times do you see MRs in floating storage?”

Euronav CEO Hugo De Stoop speculated during his company’s conference call on Thursday that floating storage would unwind with refined products being consumed first, then crude in land-based storage, then crude on tankers. Stevenson painted a different picture.

“When you talk to the customers’ side of the business, they’ll tell you we are basically at rock bottom on [refinery] utilization. We’re at 65% today in the U.S. To go below that, you basically have to shut down the whole refinery,” he explained.

“That means it’s probably not going to decline any more. The real question is: Are refineries at 65% utilization throwing off more than you can use and more than you can store? It looks like the answer is ‘yes,’ so you could actually make the argument that there might be more relative floating storage on the products side than the crude side,” said Stevenson.

The fact that refineries must keep refining at two-thirds capacity or go to zero has theoretically negative implications for crude floating storage. If crude producers like Saudi Arabia pull back quickly, and refiners still need crude to feed 65% utilization levels, floating crude storage could theoretically empty out before floating products storage if consumer demand for refined products does not bounce back sharply.

Tensions with charterers

Meanwhile, the market volatility and disruptions over recent months have led to heightened tensions between owners and charterers over business practices.

One sore point involves charterers who book a ship to store oil but do so surreptitiously via a spot voyage contract with demurrage charges paid for delays, versus a short-term time charter with a negotiated storage option. In a spot deal, payment for the voyage rate and demurrage is due after cargo discharge. In a time charter, it’s pay as you go and the storage rate is higher than the demurrage rate.

Stevenson recounted, “They’ll fix a ship in March — a spot ship mind you — and they’ll tell you they have discharge orders in July. You know what they’re doing. They’re comparing the storage rate to the demurrage rate and the storage rate is a lot higher. For us, it’s a tough call. We’ve looked at it very, very closely but I’m not sure there’s a lot we can do.”

Having a tanker float in place on storage duty can cause problems for the vessel, including bottom fouling, which will cost the owner money. “You have all kinds of things, depending where you are,” said Stevenson. “You are going to foul your bottom and do all sorts of things that you would normally calculate as part of the storage option [that are not calculated as part of demurrage] so it doesn’t make you feel too good when this happens.”

Stevenson also brought up the so-called “fixing and failing” behavior of charterers. He is the fourth tanker company CEO to publicly speak out against this practice in the past four days.

When a spot “fixture” deal is first agreed, it is “on subjects” (or “on subs”), which means the charterer has a period of time to vet the ship before “lifting subjects” and closing the deal. If the charterer does not lift subjects, the fixture fails. The subjects system is meant to give charterers time to get necessary approvals and paperwork in order, not give them a free option.

“There are a tremendous number of voyages put on subs where they [the charterers] see if they can put another ship on subs more cheaply, and if they do, they fail you and declare the other guy,” lamented Stevenson.

Asked whether the practice was limited to VLCCs, or extended to all crude and product tankers regardless of size, Kilcullen asserted, “There is a lot of abuse of putting vessels on subjects and using that as a free 24- to 48-hour option. It is absolutely happening in every asset class.” More FreightWaves/American Shipper articles by Greg Miller

Darryl Roberts

U all are a joke

Gary

Sooner or later there won’t be enough empty tankers left.