TUCSON, Ariz. — Nearly seven of 10 automobile crashes occur within 10 miles of home, according to insurance industry statistics.

It’s apparently true even for autonomous trucks.

An otherwise uneventful ride in TuSimple’s high autonomy-equipped International LT on a sunny Wednesday morning last month turned dicey when four impatient motorists raced past the truck on the left as it began a wide right turn into the company driveway.

Then, a white Jeep Compass SUV whipped by on the right, encroaching on the bike lane to complete its move. Safety driver Randy Redstone hit the brakes — hard. He thinks the robot driver would have stopped without intervention. Even though the truck’s array of cameras picked up the approaching Jeep, Redstone couldn’t take the chance.

“I’ve made that turn hundreds of times, and that was the worst I’ve ever seen,” said Redstone, who had driven big rigs for 35 years before joining TuSimple three years ago.

The recent near-miss on Old Vail Road, a two-lane blacktop in the Sonoran Desert about 15 miles east of the city, showed that even the most advanced robot trucks must be ready for stupid human tricks.

“That was about the most nutso dude I’ve ever seen,” said Chuck Price, TuSimple’s chief product officer, who sat across from me in the sleeper cab shared with the file cabinet-sized compute unit. “That guy was nuts.”

TuSimple’s 360-degree cameras recorded and played back the close call for analysis within 30 minutes. While a perfect ride would involve no disengagement of the autonomous system, there is lots to learn from an example like this.

“We can pull that data very quickly and get it in the hands of engineers extremely quickly,” Price said.

There is no shame in a disengagement. Driver monitors and engineers in the front of the cab have only one critical job: safe operation. TuSimple has no at-fault accidents in 5.4 million miles of autonomous driving.

Drivers know best

That’s in part because its 67 safety drivers have as much to say about how the trucks learn as physical test runs and computer simulations. Some of its drivers were hired following coursework at Pima Community College. Others are retirees who piled up millions of accident-free miles.

“Part of what we automate is driver best practices,” Price said. “The driver team agrees on a set of scenarios that occurred during that week, or over the last couple of weeks. They usually pick scenarios that the drivers don’t agree on. And we get them to come to a consensus on what the right behavior is.”

TuSimple’s product, engineering, algorithm and systems teams capture and incorporate that into the autonomous system, fostering AI and machine learning. They also have black box-style recordings of the driver and engineer with which to work.

“So if the triage team who’s trying to understand what happened on a run is interested, they’ll just put on headphones and listen to what they were talking about.

“If they bring us a new insight, we’ll capture it,” Price said. “Or if there’s an existing requirement that conflicts with that, we’ll discuss it. And we’ll decide, ‘OK, we’ve got to make a revision to our requirement.’”

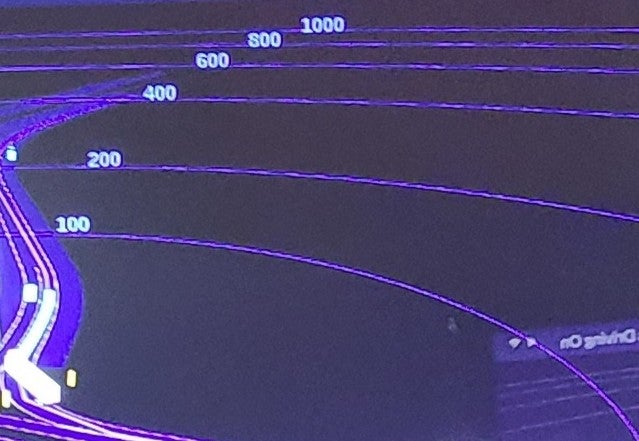

Consider two locations along Rita Road off Interstate 10 a few miles from TuSimple’s campus. Human driver experience was fed into the system that computes — not a typo — 600 trillion calculations a second.

One is near an entrance to a University of Arizona technology park with bike lanes and “lots of pedestrian chaos,” Price said. TuSimple trucks slow to 35 mph on that stretch.

The other is a partially obscured driveway to a Pilot Express fuel station with a Subway and a Burger King on the east side of Rita Road.

“There are a number of issues with that gas station,” Price said. “People are cutting out in front of trucks all the time. So, for reasons I don’t fully understand, this truck is always very hesitant around that.”

The speed of freight

Not so on I-10, where most of the westbound route toward Tucson is two or three lanes. The robot truck is assertive, suggesting a future when drivers are out and the robot makes all decisions.

In three-lane areas, the TuSimple truck most often occupied the middle lane rather than the right lane. It signaled and moved into the left lane to pass when the opportunity presented itself.

“The more information you have, the better. So we can do lane performance calculations and decide, ‘Actually, it’s going to be better to get over. That lane looks like it’s getting congested. Let’s get over early, so we don’t have to slow down,’” Price said. “Our goal is to keep the mass at the same speed as much as we can. We don’t want a lot of slowing down [or] speeding up.”

“The more information you have, the better. So we can do lane performance calculations and decide, ‘Actually, it’s going to be better to get over. That lane looks like it’s getting congested. Let’s get over early, so we don’t have to slow down.’”

Chuck Price, cheif product officer, TuSimple

The company is testing routes for UPS from Arizona to Orlando, Florida, and Charlotte, North Carolina — a nearly coast-to-coast autonomous network — with safety drivers and engineers. It is on track to pilot removing the safety driver and engineer from the cab for multiple runs over several weeks in Arizona before the end of the year.

TuSimple’s goal is to have robot drivers operate 20 hours a day to address a shortage of drivers who especially disdain long haul, where turnover runs nearly 100%. It has about 7,000 nonbinding reservations for a purpose-built Navistar Class 8 LT model. Its current fleet of 58 trucks is made up of retrofitted Peterbilt and Navistar trucks.

Hearing voices

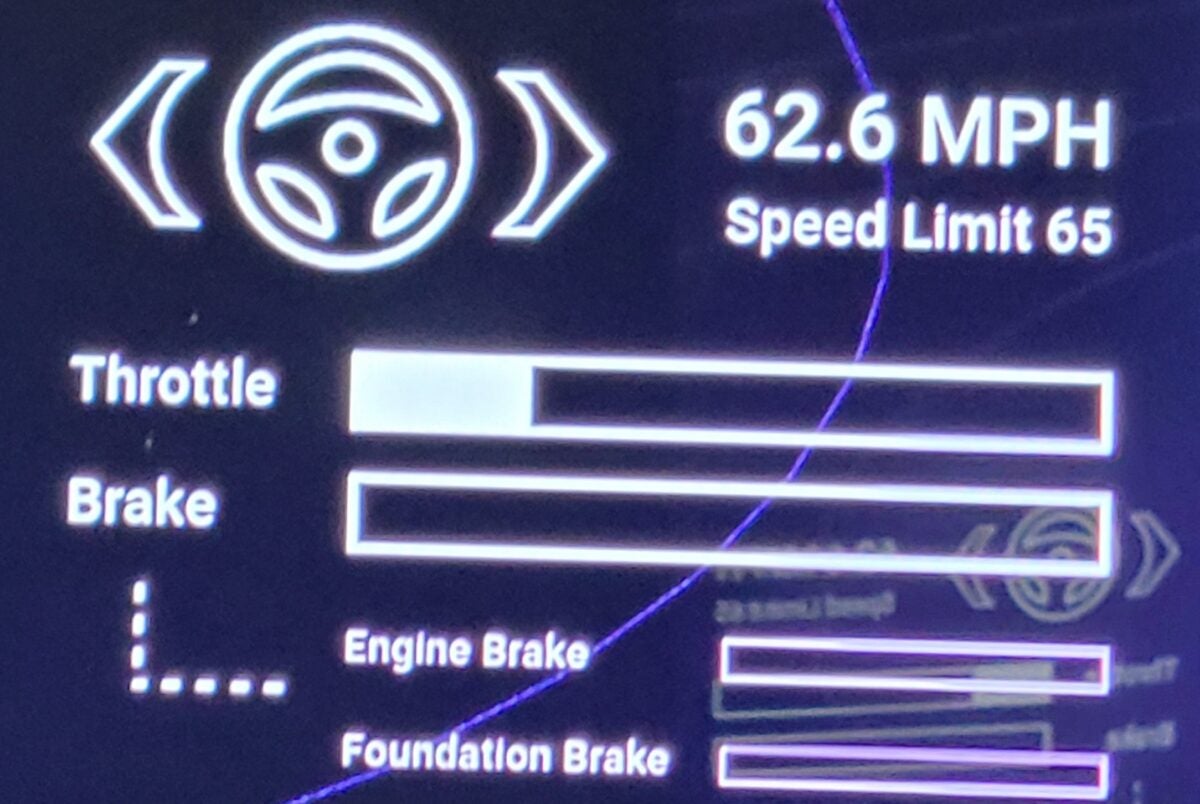

While safety drivers and engineers are in the cab, every move is broadcast. Among the notifications: “Intersection clear.” “Speed limit changing to 25.” “Pre-left change.” “Left change.” “Left bias.” “Right bias.” The occasional beep signified two messages overlapping “so it censored itself,” Price said.

Bias is the TuSimple truck’s reaction to another vehicle drifting toward it.

“The voice used to say ‘swerve.’ I didn’t like that,” Price said.

The voice typically confirms what Redstone already knows and is an improvement from the early days.

“We learned a lesson when we first started doing this back in 2017. The right seater [safety engineer] would get far more animated because they see intention on their display, and they would say, ‘It’s going to change lanes.’ And they’d start yelling to the driver, ‘It’s going to change lanes! It’s going to change lanes! It’s going to change lanes! Be ready!

“And we said, ‘You know what? This is not a good way to run a business.’ Because these [safety drivers] were having heart attacks. So we said, ‘OK, we’ll just have the [autonomous voice] talk to the driver. Relieve the pressure.’”

Said Redstone: “It lets me know the truck’s intention. And then I can make sure we’re safe when we do those things.”

Related articles:

TuSimple tops 160,000 autonomous miles with UPS, expands robot-driven freight network

Autonomous truck scaling: Is TuSimple competing with its freight with its freight customers?

Shares recover as autonomous trucking developer TuSimple’s lockup expires

David Hazen

They are allowing the trucks to stay in the 2nd lane, at 68 mph? That’s creating a hazard. I’m going to assume the speed limit is at least 70 mph which means people are going to be passing constantly, and probably on both sides. This is a terrible and dangerous idea, no matter whether it is a human or computer driving.

Fred Switzenberg

Spending billions to equip a class 8 rig (designed for humans) for AI/computer assist is stupid. Instead, pod-like robot trucks with their own dedicated lanes are the future, thereby taking humans out of the equation. Biden should’ve already had engineers working on it because they’ll never have as much money to prove its’ efficacy as they do now. The AI startups will all end up unicorn scams where everyone make huge gains: except the unwitting small guy…

Daniel B

Hopefully, the autonomous trucks can stay in there own lane and know how to signal. Then maybe they will teach human truckers to do it, too.

Rhett

“that guy was nuts” says it all. The computers don’t make judgements about people. They do not have expectations. They simply watch all directions at all times and respond to whatever happens. Nothing is ever unexpected because nothing is expected. Only human drivers would ever have a problem with the situation described. The computers can’t be surprised.

Tom Reininger

I came out of early retirement to drive trucks for a year and a half. Something I always wanted to do. There are some pretty stupid drivers out there. I hope they got the Jeep’s license number and called it in. That idiot was breaking the law and putting both the truck and his dumb ass in danger. He needs to be arrested for that.

.

And just wait until there are a few massive accidents involving autonomous trucks. imagine a mass pile up and there’s nobody in the truck when the cops show up. There’s nobody for the cops to talk to. There no driver to help move the truck to the side or out of the way. There’s no way to get the sequence of events. People are dead. it will happen lot’s of times early on and the feds will shut em all down unless they have a driver in the cab.

Autonomous trucks might work most of the time in a straight line on easy roads in good weather but on todays f—-d up roads and crowded loading docks they don’t stand a chance of working.

Kevin Robert

No way to get sequence of events? Autonomous trucks have almost 360 field of view from cameras mounted on the truck. There will be no better way to provide sequence of events than having video of exactly what happened.

Autonomous trucks will also not have to work at crowded loading docks, they’ll be in manual at that point and driven by a human driver.

The issue when it comes to autonomous trucks or vehicles in general is a lot of people have opinions on them, but very few are actually familiar with the intricacies of their systems or business model which results in tons of misinformation being spread.

Ursula Mayer

I make more then $12,000 a month online. It’s enough to comfortably replace my old jobs income, especially considering I only work about 11 to 12 hours a week from home. I was amazed how easy it was after I tried it…GOOD LUCK..

HERE ➤➤ http://www.workssilver.com