The slothlike trade moving out of Shanghai has created a short supply of raw materials traveling on the all-important intra-Asia trade route. Countries that make up this trade pipe — Vietnam, Malaysia, Taiwan, Japan, Korea, Indonesia and Cambodia — have factories waiting on crucial raw materials needed to finish goods ranging from apparel and footwear to furniture.

This pipeline saw an expansion in the trade as more American importers diversified their manufacturing out of China as a way to work around the China tariffs.

But what this pandemic has revealed is even with this “manufacturing diversification,” the dependency on China has never been fully severed. Major raw materials such as jute, cotton, silk, wool and manmade fibers used by the textile and apparel industry are sourced in China.

These raw materials are components in yarns, fabrics, fasteners, threads, pockets, shoulder pads and waistbands. In addition, trimmings (buttons, zippers, etc.), leather and rubber soles (for shoes) are made in China and transported to intra-Asian factories.

Thus, if a box of zippers is on the floor of a closed Chinese manufacturing plant or a part of the “lucky” 666 and a truck can’t pick up that box due to restrictions, the consumer is out of luck.

“We fear that the Shanghai lockdown is impacting the intra-Asian business more than Asian exports,” said Peter Sand, chief shipping analyst at Xeneta.

Data details lack of demand

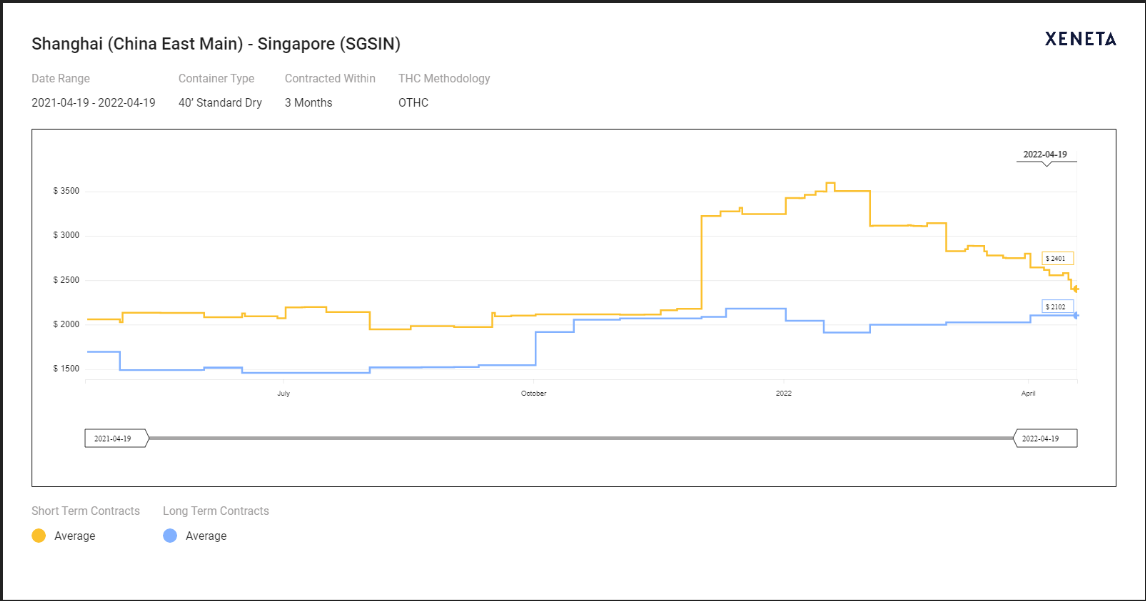

Data from Xeneta shows the drop in the short-term contracts of containers on the intra-Asia trade. Pricing is a reflection of demand — or in this case, the lack of demand.

“Not only are we worried about slowdowns in major production centers and at the world’s busiest ports, we are worried about the impact of lockdowns on the movement of both materials and finished products between China and other key Asian supplier countries,” said Nate Herman, senior vice president, policy, American Apparel & Footwear Association.

In addition to critical finishing products, chemicals are transported. Jeremy Pafford, head of North America, market development, Independent Commodity Intelligence Services, tells American Shipper one example is the chemical material used in making clothes is polyester yarn.

“Because of the shutdowns, polyester yarn inventories in China have surged as factories that would use the yarn have shut down,” Pafford said. “That has helped pressure regional prices downward up to 10% in some regions and sets up a need for polyester yarn producers to lower operating rates if more textile factories don’t reopen soon.”

Pafford said because China is the chemical manufacturing hub of Asia, the shutdowns have direct effects on producers and buyers in adjacent regions.

“These shutdowns bring a loss of demand and lower chemical prices regionally at a time when upstream costs for feedstock crude oil and natural gas are high,” he said. “Producers in the supply chain are facing pressures.”