FreightWaves Classics is sponsored by Old Dominion Freight Line — Helping the World Keep Promises. Learn more here.

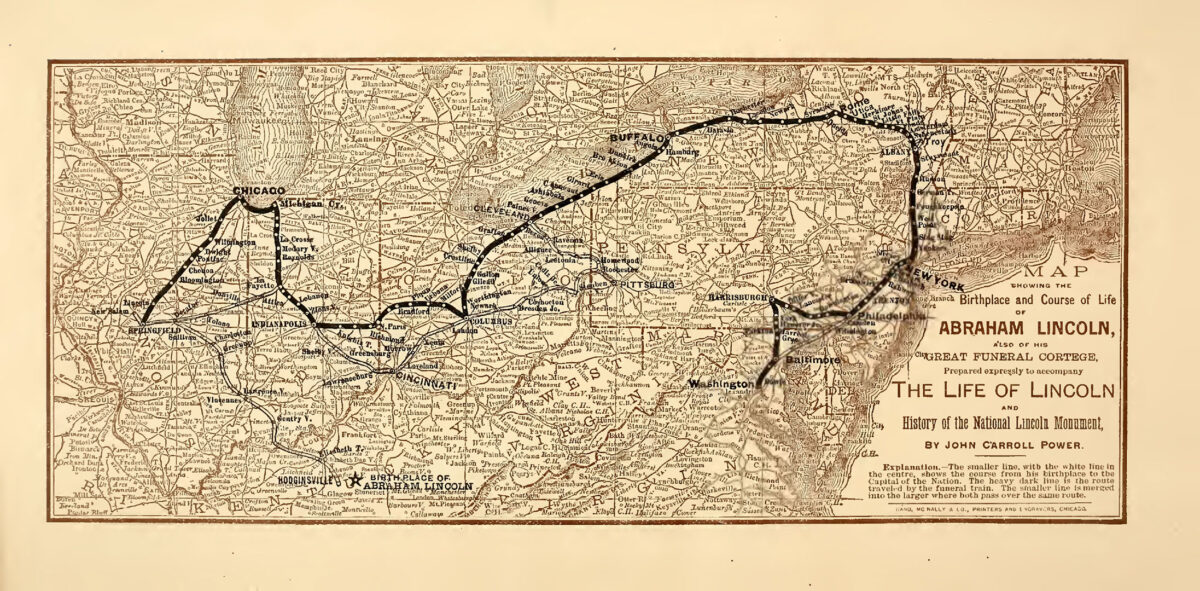

On April 15, 1865, President Abraham Lincoln was infamously assassinated. Six days later, his body began its journey to Springfield, Illinois, from Washington to be buried. He was transported by train over a route that mimicked an important trip during the president’s life — his inaugural journey.

About 300 people traveled on the funeral route in the train, including the president’s eldest living son, Robert. But also onboard was a coffin containing the body of Willie, Lincoln’s other son who died at 11 years old from typhoid fever. The boy’s body was exhumed from a cemetery in Washington to be reburied with his father. The destination of Springfield was for the president and his son to be buried in the former’s hometown.

First lady Mary Todd Lincoln sat out the journey, consumed by grief, according to reports at the time.

The steam-powered train was named The Lincoln Special, while the car itself that carried Lincoln’s coffin was named the United States. The train’s primary purpose would end up being this funeral procession, but its original purpose was for presidential travel. The idea of the train, built in 1863, was similar to the concept that is Air Force One today. The train was even equipped with 16 wheels for a smoother ride and was lavishly decorated.

Lincoln would never end up using the train while he was alive.

Both the railroad industry and the Lincoln administration were key forces in the 1830s, making the funeral procession of Lincoln’s body on a train greatly fitting as well as impactful. Not only did these two come to prominence during the same period, but Lincoln also often advocated for the use of rail early on in his political career, beginning with his push for new train lines as a young legislator. Later on but before his presidency, Lincoln also served as an attorney for numerous railroads, according to National Geographic.

Additionally, he traveled by train often throughout his presidency. The funeral procession followed his inaugural route on purpose, but it also crossed some paths that were used by slaves as they attempted to escape to the North, National Geographic noted. Soldiers during the Civil War often took the same route during its Maryland and Pennsylvania leg. Some of this leg still exists today, while most of the rest of the journey is lost to time.

Throughout the funeral procession route, American citizens gathered to mourn the loss of their president. There were nine cars total, each with black blunting draped over. They were also accompanied by a car for the hearse, which was retrofitted into what would have been Lincoln’s primary room, and horses.

“At every cross-roads the glare of innumerable torches illuminated the whole population from age to infancy kneeling on the ground, and their clergymen leading in prayers and hymns,” said one passenger on the train procession. Lincoln’s body would travel through 180 cities in seven states.

Some of the 300 people on board were funeral procession personnel and an embalmer to care for the two bodies throughout the ride.

The U.S. government sold the train to Union Pacific and transported it to Omaha, Nebraska, where it was used for numerous purposes and was stored at the Union Pacific grounds, according to the state of Nebraska.

But after numerous changes in ownership and uses, the train was lost to a grass fire near Minneapolis in 1911.

More than 150 years after Lincoln’s death, Arizona chemistry teacher and train enthusiast Wayne Wesolowski grappled with an obsession about a mystery surrounding the train. He wanted to know what the color of the “United States” car had been.

Newspaper articles from the time of the funeral reported conflicting facts, some stating that the car was a chocolate brown and others saying it was a claret red. And of course there were no color photographs during this time. Plus, because of the fire, there was no way to tell for sure anymore.

Scholars whose expertise focused on the president were unable to determine the car’s true original color. But when historians tried making a replica of the train, Wesolowski, who consulted on the project, reached out to a Minnesota man who had a window of the train in his possession.

After years of Wesolowski begging, the owner of the window finally relented and lent a piece of trim out for analysis to determine its true paint color after years of degradation, according to a USA Today article about the discovery. The man who owned the window preferred to remain anonymous. Through the color-matching process of Munsell Color System, conservator Nancy Odegaard from Arizona State Museum determined that the color was maroon: 16 parts black and four parts red.

The replica of the train debuted in 2015 and toured the Midwest for the 150th anniversary of Lincoln’s assassination.