Container shipping lines reaped massive windfalls during the COVID-era consumer boom. Different ocean carriers pursued different fleet strategies in 2020-22, from aggressively maximizing market exposure on one hand to keeping capacity flat or even reducing it on the other.

The liner bonanza isn’t over yet — high contract rates should keep outsized profits flowing well into this year. But with the historic super-cycle winding down, it’s time to take stock of how fleets evolved over the past three years.

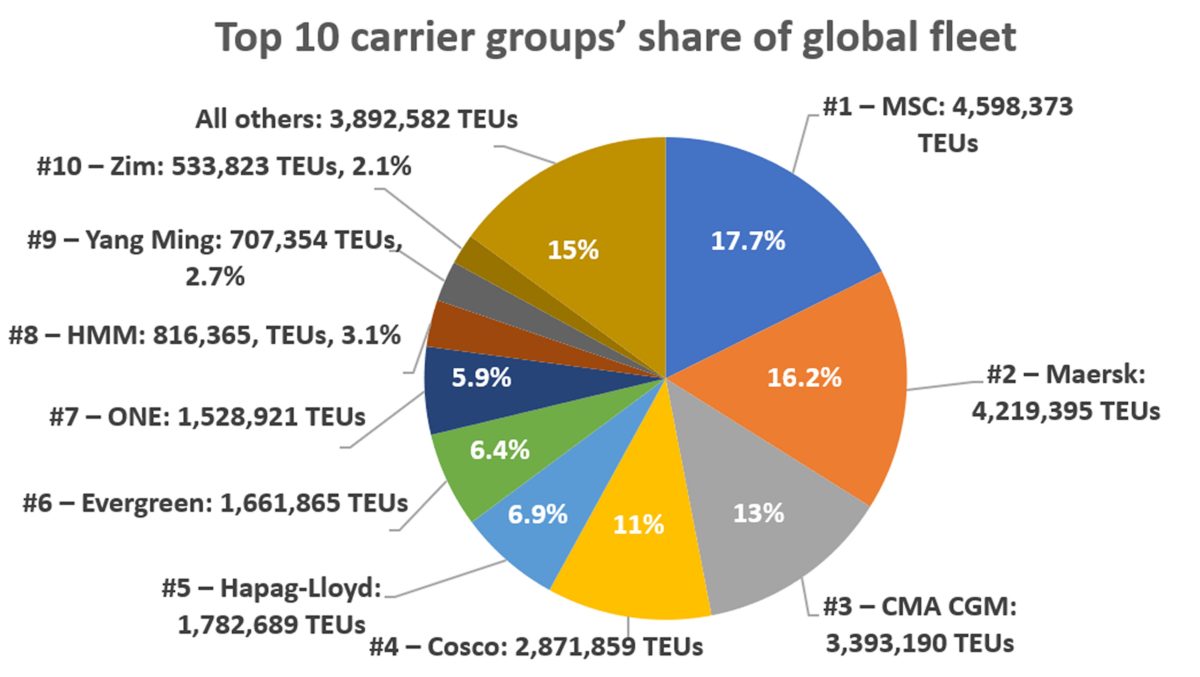

Alphaliner released its overview of 2022 fleet changes on Tuesday. Together with Alphaliner’s historical records, the data shows that the aggregate market share of the top 10 lines has stayed steady through the super-cycle — now at 85% of the global fleet versus 84% in early 2020 — but with big changes among individual players.

There are “major discrepancies between the ‘gainers’ and ‘losers,’” said Alphaliner.

The big gainers

Between Jan. 1, 2020, and Jan. 1, 2023, Alphaliner data shows the top 10 liners increased aggregate capacity by 2.6 million twenty-foot equivalent units or 13%. Five companies drove the gains.

MSC: Switzerland’s Mediterranean Shipping Co (MSC) — the world’s largest carrier since surpassing Maersk last January — has been the biggest gainer in terms of absolute capacity. Its capacity is up 832,324 TEUs or 22% over the three-year period.

According to Alphaliner, MSC increased capacity by 7.5% in 2022, primarily through second-hand acquisitions. It boosted capacity by 10.7% in 2021 through a combination of second-hand acquisitions, charters and newbuild deliveries.

CMA CGM: France’s CMA CGM is now the world’s third-largest liner operator, up from fourth place pre-pandemic.

CMA CGM grew the second fastest in terms of TEUs after MSC. It hiked capacity by 697,327 TEUs or 26% over the past three years. A portion of that growth was fortuitous timing, courtesy of newbuilds delivered in 2020-21 that were ordered before the boom. Capacity rose 7.1% last year.

HMM: The third-largest gainer in 2020-22 was South Korea’s HMM. Even more so than CMA CGM, this was not a result of COVID-era fleet strategy but just good timing.

Capacity has risen 427,839 TEUs since pre-pandemic. However, most of that growth was front-loaded in 2020, as the result of 12 newbuilding deliveries and the return of nine ships that came off charters, Alphaliner reported at the time. HMM’s growth stalled in 2022, with capacity declining 0.4% year on year.

HMM is now the world’s eighth-largest carrier, up from 10th place in January 2020. Over the past three years, it has grown capacity in percentage terms more than any other in the top 10 — 110% — albeit off a comparatively small base.

Evergreen: Taiwan’s Evergreen, the world’s sixth-largest carrier (it was seventh largest in 2020), grew capacity by 30% or 385,297 TEUs during the super-cycle period. Virtually all of that growth came in 2021-22.

“Evergreen last year took no fewer than 20 newbuildings,” wrote Alphaliner. In 2021, Evergreen’s growth was also driven by newbuilds, with 14 new vessels entering service.

Zim: While several lines grew due to newbuilds ordered pre-pandemic, others specifically increased capacity to take advantage of the booming freight market. One was MSC, which grew predominantly by buying second-hand ships. Another was Israel’s Zim (NYSE: ZIM), the 10th-largest carrier, which used a different strategy: chartering tonnage.

According to the Alphaliner data, Zim’s capacity surged by 241,520 TEUs or 83% between Jan. 1, 2020, and Jan. 1, 2023, making it the second-fastest grower in percentage terms after HMM.

It increased capacity by 29% last year, the highest percentage gain of 2022 among the top 10.

According to Alphaliner, Zim was “particularly active in the charter market, since ending its cooperation with the 2M partners [Maersk and MSC] on the Asia-Med and Asia-West Coast North America routes meant [it] needed some extra tonnage to maintain a strong presence in these trades.”

The moderate gainers — and the losers

The other five carriers in the top 10 have either grown moderately during the COVID era or dropped capacity.

Hapag-Lloyd and Yang Ming: Germany’s Hapag-Lloyd, the fifth-largest liner operator, increased capacity by 1.8% last year and by 64,800 TEUs or 4% over the past three years.

At No. 9, Taiwan’s Yang Ming upped capacity by 60,724 TEUs or 9% since pre-pandemic. It was the eighth-largest carrier in early 2020.

Maersk: Denmark’s Maersk, the world’s second-largest carrier, has kept capacity effectively flat over the past three years (up 0.6%). Maersk had long been the largest liner operator in the world until it was usurped by MSC a year ago.

“Our strategy is not to gain market share in ocean [shipping],” former Maersk CEO Soren Skou said on the company’s latest conference call. “We’re not really defining ourselves anymore in terms of ocean volumes. Our strategy is to gain share of our customers’ wallet of logistics spend.”

Maersk’s capacity fell 61,705 TEUs or 1.4% last year.

“The company had to redeliver a significant amount of chartered tonnage,” said Alphaliner. “These ships were either sold second-hand or fixed to rival carriers, which were prepared to pay higher charter rates or accept longer charter periods.”

ONE and Cosco: Japan’s Ocean Network Express (ONE), the world’s seventh-largest carrier — down from sixth pre-pandemic — reduced capacity by 0.8% last year, according to Alphaliner. Since January 2020, ONE’s capacity has fallen by 52,447 TEUs or 3%, the second-largest TEU fall among the top 10.

The carrier with the biggest TEU drop over the past three years was China’s state-owned Cosco, shedding 66,171 TEUs or 2%. It’s now the fourth-largest liner operator, pushed from the third-place slot by CMA CGM in 2021.

“The Cosco Group, including OOCL, is an interesting case since the Chinese carrier’s fleet has shrunk for the second year in a row,” Alphaliner said. “After having reduced capacity by 3.2% in 2021, the Chinese group last year saw another 2.1% decline in operated capacity.”

Newbuilds en route for top 10 lines

Changes in operating fleet size during the COVID era are only part of the story. Another is the orderbook. Ocean carriers used profits from the consumer boom to contract a massive wave of new ships for delivery in 2023 and beyond.

MSC has by far the largest orderbook, with more than double the capacity under construction of any other carrier group. According to the latest data from Alphaliner, MSC has 1.73 million TEUs on order, equating to 38% of its on-the water fleet.

Cosco has the second-most tonnage on order (884,272 TEUs), followed by CMA CGM (689,257 TEUs).

In terms of the orderbook-to-fleet ratio, Zim leads the pack, with 378,034 TEUs on order, equating to 71% of its on-the-water capacity.

In aggregate, the top 10 liner operators have 5.5 million TEUs on order equating to 25% of their existing operating capacity.

Current cargo demand projections do not support the fleet growth implied by this many orders. Rather, the new deliveries, whether owned or chartered, would to a certain extent replace existing vessels in the fleet. Carriers could sell or scrap currently owned ships and/or let existing charters expire to make room for the more cost-efficient newbuilds.

Zim CFO Xavier Destriau pointed out on his company’s latest conference call that existing charters are “bridging our current operating capacity to the scheduled delivery of chartered newbuild vessels.” He noted that Zim has 62 chartered vessels up for renewal during the period when it will take delivery of 46 chartered newbuilds.

“There are a lot of options for us to entertain as we take delivery of those ships,” Destriau said.

Click for more articles by Greg Miller

Related articles:

- Coast is (almost) clear as port congestion fades even further

- 2022’s top shipping stories: Container boom ends, war fuels tankers

- Container shipping’s ‘big unwind’: Spot rates near pre-COVID levels

- Tidal wave of new container ships: 2023-24 deliveries to break record

- Plunge in US imports accelerates; volumes near pre-COVID levels

- End of an era: Profits finally peak for shipping giant Maersk

- Here’s how container shipping lines can escape a crash in 2023