Veteran trucking executives know that good times will not last forever. Whether it is public policy, the economy, or technology innovations, the freight market is always changing.

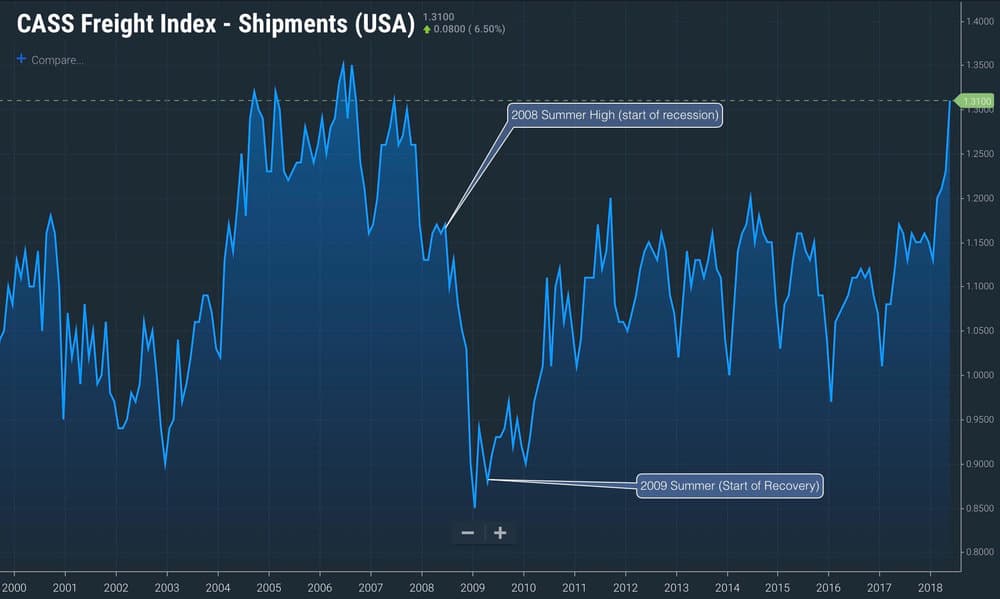

In the next decade, three major technological disruptions will drastically shrink demand for for-hire trucking services. Nearly 20% of for-hire truckload freight is at risk, putting the trucking industry at risk of experiencing one of the most drastic freight-demand declines in history, matched only by the great recession (Cass Freight Index showed a 20% volume decline between summer 2008 and summer 2009, according to SONAR).

The technologies we are talking about are not something that the industry itself is participating in, i.e. autonomous vehicles, but rather technologically-driven market changes that impact three of the segments that truckers serve.

What are they? We call then the three As. They are Amazon, autos, and agriculture (technically, retail is what is under-attack, but AAA sounds much cooler).

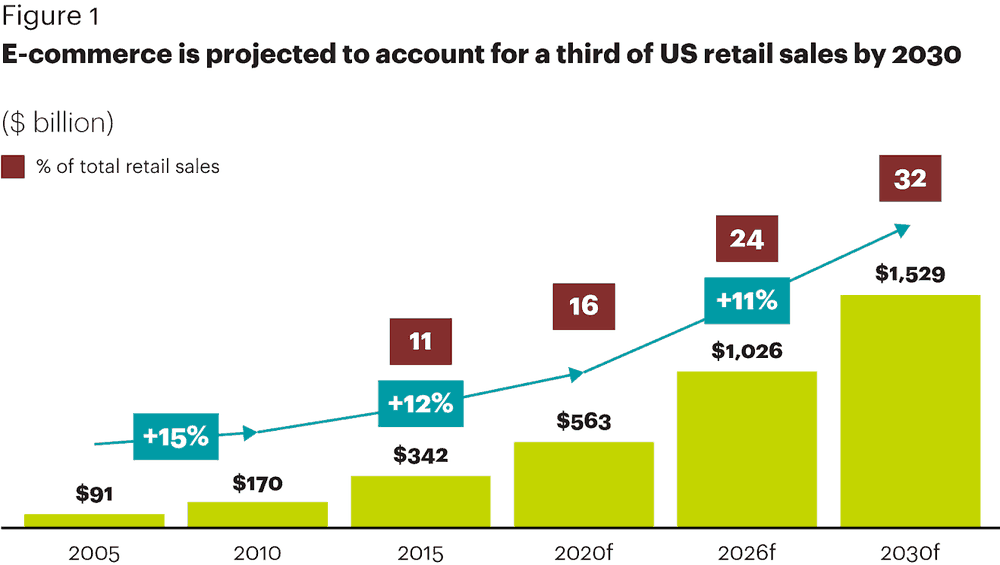

Today, e-commerce only represents 13% of all retail sales. Retail is a huge segment for trucking freight, representing 21% of all trucking freight. Quick arithmetic would tell you that e-commerce currently accounts for only 2.7% of all trucking freight.

Consultng firm A.T. Kearney estimates that e-commerce will represent nearly 32% of all retail sales by 2030 which means e-commerce should be around 7% of the entire trucking market.

Amazon

With Amazon (NASDAQ: AMZN) having nearly 50% share of e-commerce sales in the U.S., one could extrapolate that today over 3.5% of all truckload freight is in the hands of Jeff Bezos’ company.

For for-hire carriers, Amazon’s gain could be their pain. As Amazon grows retail market-share, the network becomes much denser. This enables them to build private dedicated freight networks that for-hire carriers don’t see. If Amazon were to continue to dominate e-commerce at the same percentage, they would control a purchased transportation budget of approximately $30B of truckload volume. This puts them in a category of density that is only matched by the big-three parcel carriers- UPS (NYSE:UPS), FedEx (NYSE:FDX), and USPS.

Amazon, which spends over $6B dollars today on truckload freight, has been moving more and more freight over to intermodal. Also, they plan to build out their internal linehaul network with a set of dedicated and semi-dedicated owner operators. As this linehaul network becomes more dense, it will likely look more like FedEx, a combination of for-hire linehaul carriers and leased on owner-operators. Another possibility is that Amazon’s network shapes up lke Forward Air’s (NASDAQ:FWRD) airport-to-airport owner operator network, with scheduled linehaul owner operators between terminals, augmented with a set of local P/D drivers that are either contracted to their forwarder client’s or in FWRD’s door-to-door delivery network.

Regardless, it is very clear that Amazon wants to control as much of this freight as possible, relying less and less on for-hire carriers as they ramp up.

Any volume associated with e-commerce growth is expected to take market share away from broader channels, meaning less truckload freight for traditional retail and a huge pie of truckload freight volume controlled by a single player.

Autos

Amazon’s market-share increase will only take about half of the for-hire trucking freight off the road that changes to the auto sector will.

The automotive sector is responsible for 9% of all trucking freight. If autonomous, on-demand electric vehicles become a decisive force, then it could mean that consumers in the U.S. buy less automobiles.

Tony Seba argues that we will enter a world where transportation-as-a-service will become the norm. He cites research stating that using a car service will be one-tenth of the cost of owning a vehicle. He sees the tipping point in 2021, where he states “So what happens in 2021? …that day the cost of transportation [per mile] goes down 10X?” he said. “Every time 10X occurs, it causes a disruption. Every single time.”

By 2030, Seba believes 95% of passenger miles will be on electric and autonomous vehicles and the U.S. automotive fleet will shrink 80%. Additionally, the demand for individually owned vehicles will drop 70%, and 80-90% of the current parking lots in America will be vacant.

Even if you don’t buy a transportation-as-a-service for all miles, it seems plausible that families will reduce their automobile purchases to just one vehicle and because of the durability of electric powertrains, they are likely to hold on to them much longer.

We can see this happening in major cities around the world. In recent years, luxury home builders in Vancouver have started to build homes with garages for a single car, recognizing that consumers with on-demand services for commuting were not buying two cars.

Getting back to freight, with the auto supply chain representing 9% of the trucking freight volume, knocking out 80% of this would mean a loss of around 7.2% of all trucking freight.

Agriculture

While autos are incredibly important, no sector outside of retail is important to the trucking freight markets as agriculture. Agriculture is about to get completely disrupted by technology. Indoor and vertical agriculture will have an e-commerce level impact on farming. The concept of urban agriculture means that rather than sourcing crops from farms in far-away states, food will be grown within about fifty miles of where it is consumed.

Historically, agriculture production was heavily dependent upon geography and climate conditions. It’s the reason that Idaho is the number one producer of potatoes, California leads in lettuce and avocados, Florida is covered in citrus farms, and Washington is known for apples.

Freight costs as a percentage of the final agricultural product cost, tends to be much higher than in other verticals, accounting for as much as 70% of the final cost of the product. It’s the reason that food company margins have been impacted the most by runaway freight inflation since the third quarter of 2017.

If you could eliminate climate and geography as a factor in where crops are produced, agriculture companies could locate anywhere. The key is finding an environment where nature is not a factor. Agtech startups are trying to do this very thing through the development of vertical and indoor agriculture.

The advantages of indoor agriculture include year-round production, growing crops in a controlled climate–away from pests, disease, and insects–and combined with genetically modified seeds, much greater consistency in taste, nutrition, size, shelf-life, and quality is attainable. Plus, by managing the pollination cycles indoor, you virtually eliminate the need to transport fragile bee colonies around the country.

While vertical, indoor agriculture at scale may sound like decades away, it’s not. In fact, startups like SoftBank-backed Plenty envision a set of massive indoor farms located outside of major cities to provide on-demand agriculture supplies to retailers like Walmart, Kroger, and Amazon. Vertical farming has advantages over field-based agriculture in crop yields per foot. Plus, with the combination of ag science and climate control, crop producers can achieve far more consistency in the product.

Consumers prefer to purchase their produce in person to ensure quality, color, and freshness. Any newly married man knows the feeling of being scolded for picking a cantaloupe that doesn’t match his new wife’s preferences. By standardizing this, online ordering could bring far greater consumer satisfaction with fresh fruits and vegetables delivered to their door.

Vertical farming also means better water conservation, lower labor costs, and if food is produced locally, it means higher nutritional value by the time consumers eat it. According to Plenty, produce loses 45% of its nutritional value by the time it makes it to the shelf.

The other part of the ag freight market has to do with lab-grown meat. Lab grown meats are genetically identical to animal raised meat, except they are grown using in-vetro cells from live animals and replicated.

According to CNN, “Clean meat production could also result in 78% to 96% lower greenhouse gas emissions, use 7% to 45% less energy, 99% less land, and 82% to 96% less water than traditional methods, according to a study from the University of Oxford.”

Lab grown meat is expected to hit store shelves by the end of 2018 and should be in mass-market production by 2021. As for consumer acceptance, one-third of consumers recently stated they would be willing to regularly eat lab-grown meat. According to CNBC, Bruce Friedrich, the CEO and co-founder of a think tank accelerator called The Good Food Institute, believes lab-grown meat will be cost-competitive within 10 years.

While the prospect of eating meat that is grown in a lab feels creepy, consumers already eat meat that is heavily processed before it hits the table (McNuggets for instance). Getting meat that doesn’t contain antibotics or potential pathogens would seem appealing.

If lab grown meat takes off, it will mean far fewer freight ton-miles, even if the meat is trucked around the country. During butchering and processing of animals, as much as 80% of the weight of the animal gets discarded.

According to the Transportation Research Board, agricultural products account for 31% of total ton-miles of freight moved. Furthermore, trucks move over 90% of the nation’s fresh fruits and vegetables (by market share) and 95% of livestock transportation.

Produce and livestock trucking is estimated to generate nearly 18% of trucking industry revenue. If you source food farmed locally, you have no need to truck long distances. If just half of the food goes this way by 2030, 9% of freight volume would be at risk.

What does all this mean for the freight markets?

With three major shipper segments under attack, the industry might see it’s first perpetual decline since deregulation. This will certainly play out in the freight markets and should keep trucking rates in check as the decade carries on.

For the next few years, the trucking carriers will enjoy tight conditions and high demand, but about the turn of the decade, conditions will start to change. By 2030, consumers will likely be buying their daily produce on Amazon that was farmed locally indoors with a side-order of lab filet, delivered in an autonomous vehicle direct to their home. The trucking industry, faced with less and less freight, will also let look dramatically different as a result.

Stay up-to-date with the latest commentary and insights on FreightTech and the impact to the markets by subscribing.