Utilities aim to meet ambitious goals of reducing emissions across western U.S., but technology and financing remain big hurdles.

The biggest utilities along the West Coast are taking the first step in electrifying one of the busiest freight lanes in the U.S.

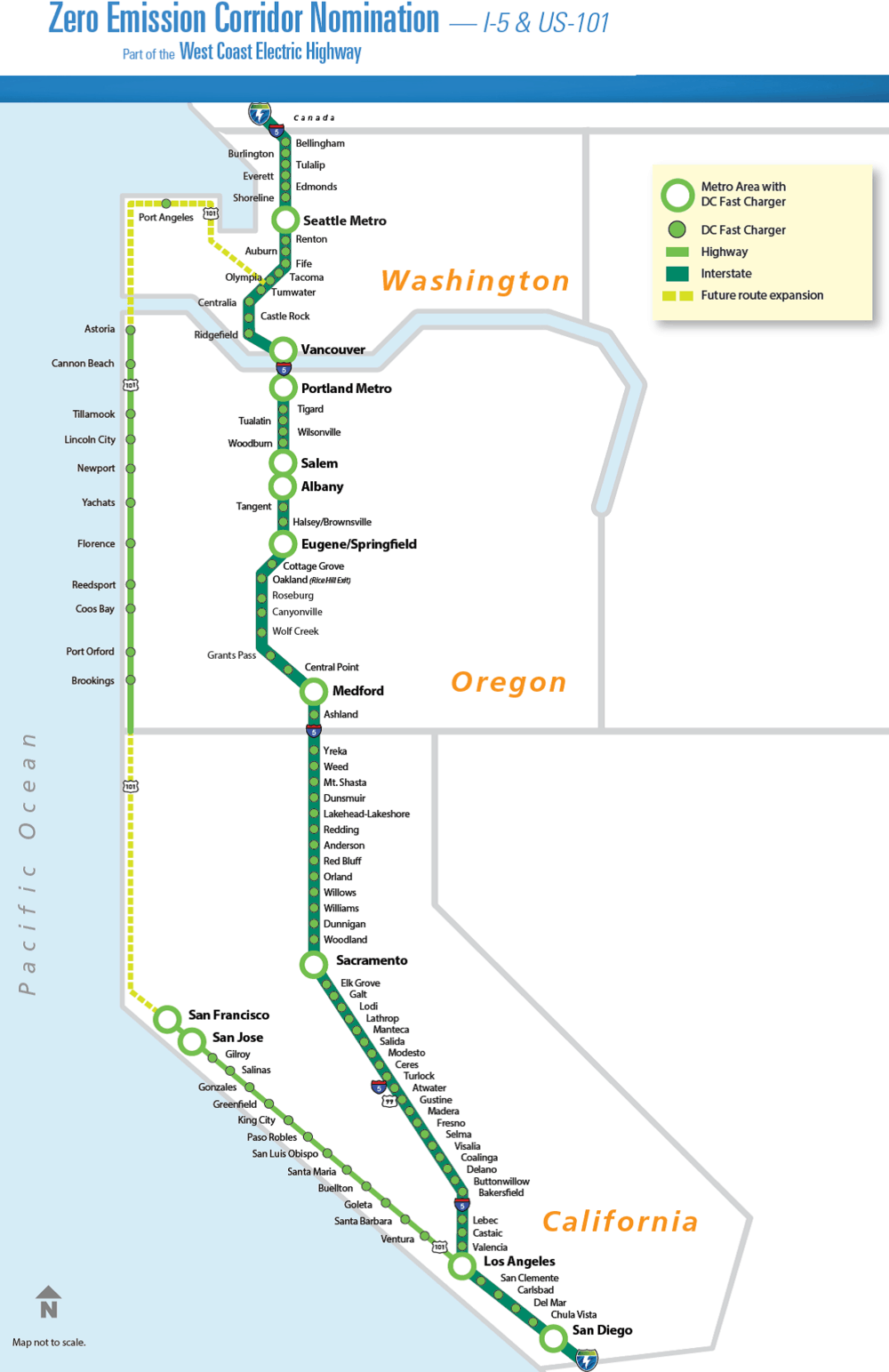

Utilities including Pacific Gas and Electric (NYSE: PCG), Southern California Edison, Puget Sound Energy and Portland General Electric (NYSE: POR) are among the participants in a study to put up a string of electric charging stations for medium- and heavy-duty trucks along the 1,350 miles of Interstate 5 (I-5), which stretches from Mexican border to the Canadian border.

If the plan goes forward, it could provide a big boost to the battery-electric truck models coming out from Volvo (Nasdaq OMX: VOLV), Daimler (FSE: DAI), Paccar (Nasdaq: PCAR), Tesla and others. But the size and scale of the project, along with the current state of battery-electric truck technology, mean it will take some years before the project ever comes to fruition.

In total, nine regional electric utilities and two agencies representing 24 city utilities will take part in the study, called the West Coast Clean Transit Corridor Initiative.

Katie Sloan, who heads the new group along with Southern California Edison’s transportation projects, said the initiative will look at how to ensure “I-5, the lifeline of goods transportation up and down the West Coast, is equipped with sufficient chargers to support electric trucks.”

Much of I-5 is designated as a “major freight corridor” by the U.S. Department of Transportation, meaning more than 8,500 trucks per day travel that highway. The California portion of that highway also has one of the highest amounts of trucks in the market nationwide. (SONAR: TRUK.FAT)

But the traffic on I-5 is one impediment to the ambitious environmental goals many of the western states are embracing.

In 2018 California was able to meet its goal of lowering greenhouse gas emissions to below 1990 levels with reductions in all its carbon-emitting sectors, except for transportation. Oregon legislators introduced a cap-and-trade plan, which is already in use in California, that would also put a cost on emitting carbon into the atmosphere.

Moving freight on I-5 is “crucially important to the economies of Washington, Oregon and California,” Sloan said. “However, it is also a major source of greenhouse gas emissions, air pollution and toxic vehicle fumes.”

To reduce those emissions, “the largest near-term opportunity is electrifying transportation,” Sloan said.

Many of the utilities are working on individual projects within their markets. Southern California Edison said the utility is launching its “Charge Ready” charging stations for commercial trucks by next month.

Southern California Edison Vice President Caroline Choi said that program will support 8,000 vehicles at 800 sites in the Southern California market. But the amount of freight on I-5 means one agency alone will not be able to do the job.

“In order to support long-haul transportation, we need an effort that is coordinated across county and states lines,” Choi said. “This study will help Southern California and the West Coast region to make the [electric truck] transition economically and safely.”

At this point, though, the scale, technology and changes to the underlying electric grid to install charging stations remain unknown, with the utilities expected to publish their results by the end of 2019.

In a report on electric truck charging infrastructure, the North American Council for Freight Efficiency (NACFE) said the type of “fast-charging” stations that the group is considering could cost between $15,000 and $90,000 each. Each station could need up to one megawatt of power, or about one-and-a-half month’s of electricity consumption for homes on the West Coast.

The big hurdle for electric trucks remains the range and the charging time. NACFE Executive Director Mike Roeth said the current battery technology allows for a 250- to 300-mile driving range. And getting to a full charge on an empty battery can take up to eight hours.

He said long-haul trucks could top off at a charging station. But even that could take up to two hours, which would count against a driver’s hours of service.

“Along freeways, we think the truck stop-type of electric charging is a long way off,” Roeth said.

Referring to other fueling methods that failed to find significant market share, “so many of the truck stops have yellow tape around their (compressed natural gas) station; we would rather not have that down the road,” he added.

Roeth expects the quickest uptake in truck charging stations will be in dedicated fleets with point-to-point transportation needs. Companies such as Frito-Lay (NYSE: PEP), which is ordering up to 100 Tesla trucks, can place charging stations at manufacturing plants, warehouses and distribution centers.

“Day cab tractors with dedicated routes and charging stations at one end and the other will come quicker than what the average person thinks,” Roeth said.

The utilities also recognize that the infrastructure could take years to develop due to the thicket of interests. Some of the utilities are investor-owned while others will have to go to a public utility commission for approval of the project.

Likewise, one of the study’s largest participants, Pacific Gas & Electric, is going through a $30 billion bankruptcy case due to the role its power lines played in sparking wildfires across California.

Nonetheless, Choi said the ability of utilities to finance and to plan long-term projects make electric truck charging an effort they could tackle.

“Due to the nascency of the market, it may not be an opportunity for revenue but the role of the utility is important because we are in it for the long-haul, no pun intended,” Choi said. “We have the opportunity for patient capital that others may not have.”