By now, most industry observers and analysts agree that the U.S. truckload market has slowed significantly, part of a broader goods normalization and hangover in our COVID-recovery. Multiple spot rate benchmarks have been falling for months; capacity metrics have loosened. Accepted contract loads (CLAV.USA) peaked in October 2021 and just took a sharper turn downward.

National outbound tender rejections (OTRI.USA), which measure the percentage of truckload shipments tendered by shippers that are rejected by trucking carriers, fell to a new cycle low of 5.05%. That’s a very low level last seen in May 2020, when the economy was climbing out of its lockdown-induced deep freeze. When freight is plentiful and trucking carriers have options, they reject contract shipments for higher-paying spot loads and tender rejections rise. But when the market softens, carriers worry about filling their trucks and take all the contract freight they can get, lowering tender rejections.

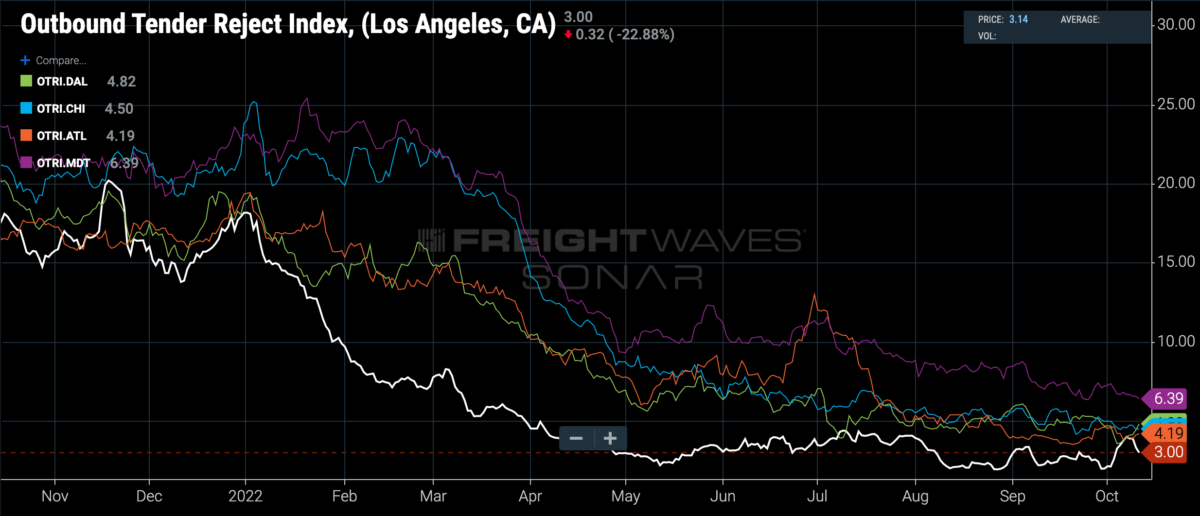

Trucking carriers have reacted to the slowing business environment by deploying their assets on power lanes between major markets that are still dense with activity. But that tactic has had the effect of driving tender rejections in the largest U.S. markets even lower than the national average.

Trucking carriers are only rejecting 3% of contract loads outbound from Los Angeles and 4.5% of loads outbound from Chicago. Of the five largest markets, only Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, tender rejections (OTRI.MDT) at 6.39% are higher than the national average. That higher floor may be supported by the reefer market out of Harrisburg, which is rejecting 7.5% of outbound loads, and may tighten further as temperature-controlled food imports into Philadelphia peak during the Northeast winter.

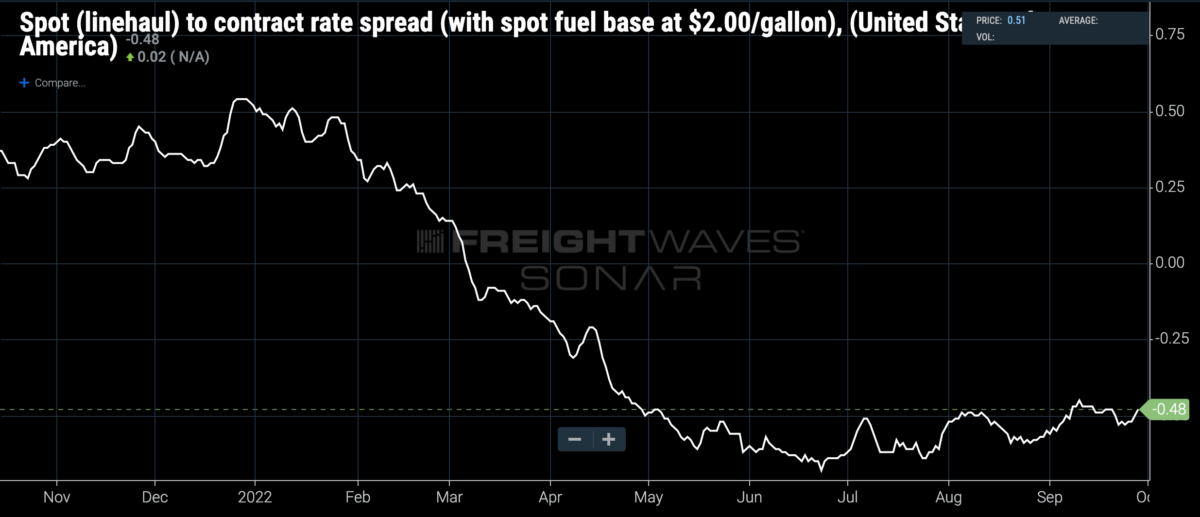

Spot rates fell hard in the first half of 2022, but national averages have been somewhat range-bound since mid-August. The National Truckload Index, Daily Report – Linehaul rate (NTIDL.USA) is now at $1.90 per mile, well below the Van Contract Rate Per Mile, Initial Report (VCRPM1.USA) at $2.70, which itself has fallen about 25 cents from its mid-June peak.

There are cleavages in the contract truckload market, though, that national benchmarks may sometimes obscure.

“I think there is a big gap between live/live contract and drop/drop contract that nobody is talking about,” said William Kerr, president at Edge Logistics, a tech-enabled freight brokerage based in Chicago projected to generate $150 million in gross revenues this year. “When you look at big data rates, you have to take the contract with a grain of salt because 70% of the data is drop/drop.”

Kerr referred to the distinction between truckload shipments that are loaded and unloaded live, as the driver in his or her truck waits at the dock, and drop shipments in which the driver picks up and drops off preloaded trailers without having to wait for loading and unloading.

Setting up a drop trailer pool with a shipper customer requires a higher level of commitment from the carrier and a closer, more collaborative relationship with the shipper customer to manage the assets, and Kerr suggested that the contract rates for that kind of service were holding up better than those for live/live shipments. On the other hand, live/live shipments can be handled by carriers hired the day of, so non-asset freight brokerages have typically concentrated on that kind of business.

“I think the correction has been long underway in the live/live market,” Kerr added. “Once we get to February and March and the drop/drop market rolls over, live/live spot will come roaring back.”

The spread between spot and contract rates blew out into negative territory as spot fell hard but has been closing back up toward zero as spot rates stabilized and contract rates started to react to downward pressure. Kerr confirmed that contract volumes were lower than projected, revenue per load was down and net revenue dollars per load were down but that gross margins were holding steady. That implies that in the freight brokerages’ share of the truckload market, both contract and spot rates are actually lower than market averages with heavy exposure to asset-based carriers’ transactions and drop/drop shipments.

Like other freight brokerage executives who have spoken to FreightWaves in the past month — including Doug Waggoner, CEO of Echo Global Logistics — Kerr seemed to sense pockets of instability and unsound capacity that were primed for the next upcycle. Last month, Waggoner warned that lower truck orders portended an equipment-driven capacity crunch, perhaps catalyzed by an unforeseeable external event sometime in the next year. Kerr’s hunch has more to do with the internal dynamics of the market and the sequence in which capacity and volume enter and exit different market segments.

David Spencer, director of business intelligence at Arrive Logistics, a large Austin, Texas-based freight brokerage that will record approximately $2.5 billion in gross revenue this year, agreed that contract rates for drop trailer shipments tend to be stickier because those carriers staging drop trailers at customer locations are harder to replace. So when contract rates are falling, drop/drop rates will be more stable and lag behind any price move.

But Spencer cautioned that the economics of drop/drop loads for carriers can be complex: Although they have to provide equipment, they gain efficiencies from quick drop-and-hook freight, allowing them to run more miles. In other words, even if rates for drop/drop loads move more slowly, they aren’t necessarily higher than live/live rates—usually only for multi-day transits, Spencer said.

That said, there’s a plausible way that a capacity-driven turnup could materialize in 2023. If shippers rapidly shift strategies from focusing on maintaining service to managing spend because capacity seems abundant, they might well de-emphasize drop trailer networks and other contracted and semi-dedicated arrangements in favor of cheap spot capacity. Enterprise carriers, many of which have already paused growing their fleets because of difficulty recruiting and retaining drivers, could find new equipment harder to procure next year. More freight could be pushed into the spot market that way and rates could turn up again, especially if enough time has passed for significant spot capacity to exit the market.

Time will tell, but for now, with August real goods spending down 0.2% year over year, most parts of the truckload market are on a clear downward glide.

Anonymous

Funny how truckers throw out the going on “strike” card because of the market correcting itself back to what it was before Covid. When Covid happened carriers were able to name their price. Reefer loads out of California to the east coast back in the heart of Covid carriers were asking for 15k. Really? That’s astronomical pricing. Now that tables have turned in the eyes of the carriers its the brokers fault? No that’s not true at all. You had a inflation of new carriers getting their own trucks and MC’s thinking this is a norm for that kind of pay and now you are seeing those new carriers go out of business because they cant afford the truck and overhead. What goes up must come down. If anything blame the inflation of new carriers that flooded the market, that may be the reason these prices are going down. This market has its ebs and flows but be realistic, Covid was not a norm for rates so don’t blame brokers and customers for the market finally correcting itself.

David Rachlin

Drivers Should Shut Down then the rates will go back up. The Brokers are Stealing from the Drivers Owner Operators Cost of Fuel Maintance Insurance all time outrageous. How about the Cost to Purchase The Trucks that Move America all time high.Price of Fuel is climbing the the 25 cent tax per gallon was only Temporary. Inflation is up because Manufacturers can’t produce Fast enough. How about All the Freight still on Ships. Florida is offering to pay for CDL Training . America Can’t fix it self People still don’t want to work

Alex D.

trucker strike.. needs to happen don’t need to block highways or jam up roads to get our point across. just park it. park it at your house. the truck stop or whatever it may be and provide NO SERVICE. no loads moved no fuel delivered no food delivered. nothing 1 week. and the rates will go crazy

Jamie

well after reading this it is very disappointing that the rates reflect what the brokers want to pay! the customers to the brokers are paying the brokers big bucks to move the freight and paying less to the trucks and people can say all they want about the market and all that crap when the bottom line is that there are WAY TO MANY REGULATIONS BY PEOPLE THAT HAVE NO IDEA WHAT IT COSTS TO RUN ONE TRUCK NOR DRIVE ON THESE HWYS, ROADS WITH TODAYS GENERATION AND BROKERS ARE SCREWING OVER THE TRUCKS!

Joe Muncie

It’s a lie that the price of goods has increased because of cost the of transportation.Carriers are not seeing that increase in the rates.If shippers and/or brokers continue to keep the fuel surcharge they will regret it.They are forcing carriers out of business.

Pretty soon they will beg for carriers.

Carolyn Watson

The rates need to come up, the rates need to meet the cost of fuel.

We are owner operator and are disgusted with the rates we are offered to haul freight.

It is all over the news that the price for goods is increasing because it costs more to transport goods. It does cost more to haul goods but the truck drivers who actually pay for fuel are not seeing the increase, actually the rates are worse than they were before the fuel surge because of the Brandon Administration choosing to fist bump our enemies and make them rich onstead of drilling here in the USA! Lets get the democrats out of office, get Trump Policies back in place.

Stephen Webster

too many trucks

We need to reduce the number of new power units and stop foreign drivers coming into🇨🇦 for any company that does not have a good plan to look after sick injured drivers and those that got covid and are long haulers with problems. A group of health professionals in🇨🇦 are pushing for 11 paid sick days and priority care for truck drivers that are employed or lease ops

I understand if they win their court case this will limit foreign students as drivers coming to Canada 🇨🇦