The news is brimming with stories on businesses that are “dead men walking.” Movie theaters. Cruise lines. Retail outlets. Event organizers. Big-city offices. Ocean shipping doesn’t fall in this category — there’s no existential threat to transporting cargo by sea. Yet the travails of 2020 raise the question: Do shipowners still have a long-term future on Wall Street?

Looking to 2021 and beyond, can U.S.-listed shipping stocks recover or will they sink further toward penny-stock oblivion?

To answer that question, FreightWaves interviewed Jefferies shipping analyst Randy Giveans, Marine Money President Matt McCleery and Deutsche Bank transportation analyst Amit Mehrotra.

All three are optimistic that there is indeed a way forward.

“When people start to ask this kind of question, you know you’re closer to that point where you get back. It’s a darkest-before-the-dawn kind of thing,” asserted Mehrotra. “I mean, it wasn’t that long ago when my phone was ringing off the hook about tanker stocks.”

Shipping’s shrinking market cap

Shipowners only came to Wall Street in earnest starting in the mid-2000s. There have been depressed years since then — particularly 2009 — but 2020 feels worse sentiment-wise than any other.

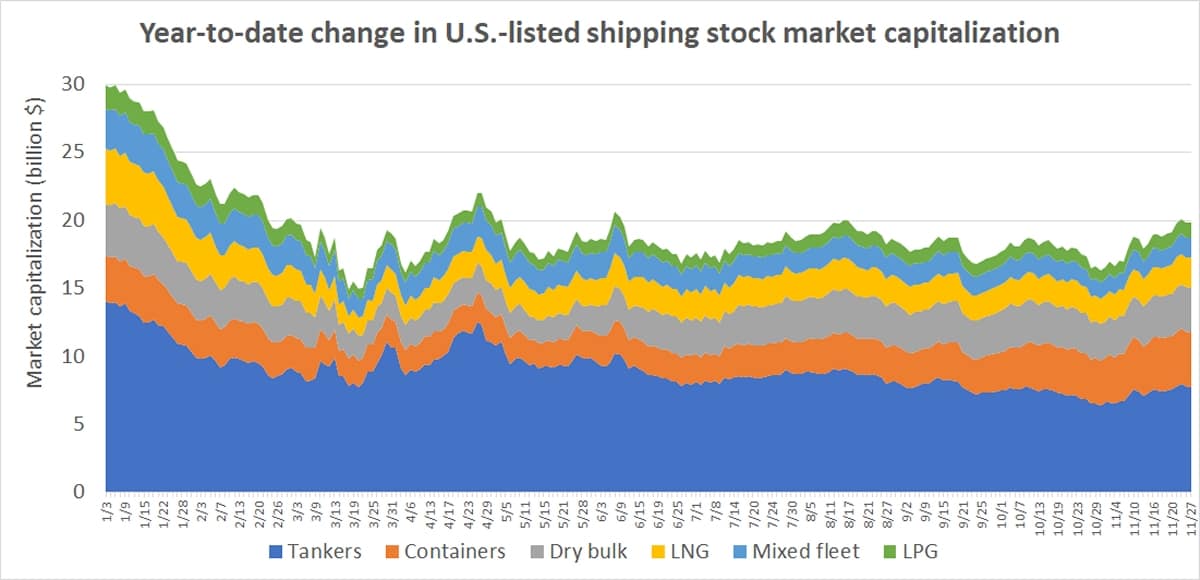

FreightWaves analyzed daily market-capitalization data from Koyfin of 50 NYSE and NASDAQ-listed shipping equities. (Shipowners that are part of conglomerates with nonshipping entities were excluded, as were offshore service providers and American Depositary Receipts.)

The data shows that the market cap of the entire universe of U.S.-listed shipowners fell from $29.9 billion at the beginning of this year to $19.8 billion as of last Friday. That’s a year-to-date decline of 34% from an already very low base. The market cap of Amazon (NASDAQ: AMZN) is now 80 times that of all U.S.-listed shipowners combined.

The median market cap of U.S.-listed shipping stocks has fallen deep into micro-cap territory: from $420 million on Jan. 2 to a mere $209 million.

By sector, the aggregate market cap of tanker stocks — by far the largest segment in terms of valuation — is down 44% year-to-date. Market caps of mixed-fleet owners are down 51%, liquefied natural gas (LNG) carriers 45%, liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) carriers 35% and dry bulk owners 15%.

Bucking the trend, the market cap of container-ship owners is up 19% year-to-date. The main driver is Matson (NYSE: MATX). Matson is the sole U.S.-listed container-shipping company that is a liner operator, not a ship lessor.

Matson’s market cap is up 47% year-to-date. It is now more than 50% higher than the market cap of the second-largest pure public shipowner, tanker owner Euronav (NYSE: EURN). Among U.S.-listed shipping stocks, Matson is the biggest winner of 2020 by a very wide margin.

Vaccine and a new president

The good news on shipping market caps is that as a whole, they bottomed on March 20 at $14.9 billion and are up 33% since then. More improvements are expected off their low base in 2021, for several reasons.

First, Joe Biden will become the president on Jan. 20. This should somewhat alleviate the stock sentiment overhang from the outgoing Trump administration’s trade war. According to Giveans, “Biden will probably be better for dry bulk and containers. And if you look solely at the trade war, I don’t think Biden will be as hawkish as the Trump administration, so that could be a tailwind.”

Second, vaccines should change consumer behavior. According to Mehrotra, “At some point in 2021, when there is a vaccine, you’re going to see an incredible pent-up demand release. You saw it when the initial restrictions started getting eased back in May and June. And I think you’ll see the same thing on a much bigger scale at some point in 2021.”

Giveans explained, “Shipping stocks had been pushed down the most when things were terrible [from the pandemic] and they should rally the most when things are good [from the vaccine].”

The key vaccine-related indicator to watch for tanker shares is air travel. Global oil demand has fallen around 8% in the wake of the coronavirus, largely due to loss of demand for jet fuel.

Growth-to-value stock rotation

Investors buy growth stocks based on future potential. Investors buy value stocks because they believe the stocks are cheap. Shipping stocks are value stocks, whereas Tesla (NASDAQ: TSLA) is the epitome of a growth stock (if not a bubble stock).

“This year was all about momentum growth names. Just look at the charts for Apple [NASDAQ: AAPL], Amazon, Zoom [NASDAQ: ZM], Tesla and anything tech,” said Giveans. “But the last few weeks have shown a rotation of money from some of the big growthy tech names to more cyclical and value-oriented names. That can really move the needle [for shipping stocks].

According to McCleery, “The investor bias has been towards the asset-light, high-growth businesses. Shipping is the opposite of that.”

Not only is it asset-intensive, but “there’s not much demand growth, at around 2% per year, and it’s highly cyclical. So, shipping is part of a really out-of-favor sector. But that will change,” he maintained.

McCleery also pointed out that shipping might follow Tesla’s playbook someday. “General Motors [NYSE: GM] trades at around six times earnings and Tesla is at around 500 times earnings because investors look at it as a tech company, not a car company. Why couldn’t somebody do the same thing in shipping, whether it’s using hydrogen [propulsion] or something else?”

Supply upside and decarbonization

Yet another positive for shipping stocks: The vessel-supply outlook looks very attractive for all segments except LNG. Orderbooks are historically low, a positive for future rates.

“I think a lot of people are seeing that supply side is looking very good,” said Giveans. “With the orderbooks so low, they just need to see some stability and confidence in demand. I see pretty attractive markets in late 2021 and 2022, although that’s certainly not priced in right now.”

“I have zero doubt that we are going to see some very strong markets in the medium term as an under-built fleet meets with demand shocks,” said McCleery. “This will absolutely arouse the animal spirits of investors.”

The newbuilding outlook is intertwined with expectations for International Maritime Organization (IMO) decarbonization rules. These rules have yet to be defined, but McCleery sees an opportunity for shipping equities to benefit from the future decarbonization push.

“The point I tried to make in my book [“Exit Strategy”] is that decarbonization is probably the greatest opportunity I’ve seen in my career for shipping to innovate, participate in a cooperative way with charterers and banks, and reinvigorate the business model,” he said. “You have a chance to rethink the whole structure of the business, from the way ships are run to the costs to the speeds they go.”

Decarbonization is already paying off for listed shipowners. The threat alone of future carbon rules has spawned uncertainty on ship designs, which has helped keep the lid on new orders, a plus for the future supply-demand balance.

The 2021 bear scenario

Low orders, vaccines, more air travel, the winding down the trade war, the value-to-growth rotation — it all sounds like a recipe for a shipping-stock renaissance in 2021-2022. But for each of these pros, there’s a con counterargument.

World governments may not agree on decarbonization efforts soon enough, if at all. Ultimately, shipowners may opt to pull the trigger and order traditional or dual-fuel designs. State-linked Asian entities may also order ships to keep Asian yards afloat.

The key trade dispute for shipping stocks is between the U.S. and China, and Biden may be just as aggressive toward China as Trump.

Despite vaccines, economies may suffer deep recessions due to job losses. Today’s booming container-shipping volumes may be borrowed from future demand. The tanker floating-storage hangover may last even longer than expected. Oil demand in general may be peaking.

Furthermore, shipping stocks need more than retail traders to obtain better valuations and trading liquidity. They need large institutional investors, as well. Now that market caps have sunk this low, it will be even more challenging to bring big institutional investors back into the fold.

Wooing institutional investors back

Public shipping equities have been advantageous for their sponsors, particularly those with private management companies and private fleets. Sponsors can use the public entity to earn related-party fees and offset their overall downcycle risk. Shipping company executives enjoy generous compensation packages.

Outside the companies, the high volatility of public shipping equities has also been advantageous to stock traders. But these stocks have generally not been profitable for long-term investors.

Evercore ISI analyst Jon Chappell maintained in a research note in July that “broader institutional support … will not emerge as long as there are brief super-spikes directly followed by long downturns.” With the exception of the one-off 2003-2008 China-driven boom, shipping markets have almost always followed a pattern of “brief super-spikes directly followed by long downturns.”

“Institutional investors want stabilization,” said Giveans. “Obviously the surge in tanker rates in March and April was great for profitability and for trading. But not for investing. As we knew then and we certainly know now, a lot of that was pulled-forward demand.”

“The companies haven’t been able to build value over time,” acknowledged McCleery. “The long-term buy-and-hold story has been challenging. A lot of people have made money trading these stocks, but the question I ask myself is: How does that [trading] help the industry? You need equity offerings to work for the investors.”

Structural hurdle to stability and sustainability

McCleery believes that, in general, shipowners will have less financial leverage going forward. “They can’t get super-aggressive financing anymore,” he said. Less cheap debt will also equate to fewer buy-low-sell-high asset plays, he believes.

Lower financial leverage and fewer asset plays would put more decision-maker focus on operating leverage — i.e., exposure to freight rates.

Operating leverage paints shipowner equities into a corner. They effectively become commoditized plays on the demand for the cargo they carry, whether it’s oil or iron ore or containerized goods. This underlying demand is highly uncertain and frequently driven by unpredictable geopolitical and economic events.

As Karatzas Marine Advisors founder Basil Karatzas told FreightWaves earlier this year, “The problem is that even for companies with a large number of vessels, it’s about direct market exposure [to freight rates]. They do not provide anything more. So, it’s always highly volatile.”

That may be music to the ears of micro-cap stock traders. But it may not offer the stabilization and sustainability that larger institutional investors look for.

Getting big

What would be the best public vehicle to woo institutional buyers? Giveans believes the ideal shipowner stock would be “something with a large market cap, large trading liquidity, a dividend policy and forward looking on ESG [environmental, social and governance].”

Asked how shipowner stocks can ever become more than commoditized cargo bets, McCleery answered, “The way to get out of that is to get big and well-capitalized and find a home within the universe of transportation investors” and 401K portfolios.

But calls for shipping companies to “get big” via ownership consolidation have been voiced for decades. Outside of container liners — which, with the exception of Matson, are not traded in the U.S. — it hasn’t happened.

Nor is getting big something that listed owners can do anytime soon.

The NAV discount conundrum

In 2020, most shipping stocks are trading at steep discounts to net asset value (NAV), the current resale value of the fleet plus other assets, minus liabilities. “Most of the companies are trading at between 50% to 75% of NAV,” said McCleery, who conceded, “How do you do anything [with that NAV discount]? How can you even make the case that you should buy a ship? You’re kind of paralyzed, right?”

According to Mehrotra, “The entire reason for a shipping company to be in the public market — whether it’s dry bulk, tankers or containers — is that you ultimately want your stock to trade above NAV. That will give you a perpetual share-capital base to fund accretive growth. You can issue shares and buy ships. That’s the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow.

“If there’s no way of getting there, there’s no reason for a shipping company to be public,” said Mehrotra.

The perennial conundrum for public shipowners — epitomized by the unpredictable and market-transforming events of 2020 — is that the share price discount to NAV, and thus the path to that pot of gold, appears largely outside of management’s control. Click for more FreightWaves/American Shipper articles by Greg Miller

MORE ON SHIPPING STOCKS: A lost decade for shipping shares: see story here. Shipowners with shares worth pennies rake in millions: see story here. Robinhood’s topsy-turvy Top 10 shipping stocks: see story here.

Mr khurram Shahzad

Please help me sir my package parcel delivery Pakistan Punjab city Gujranwala village Bujumal post code 52340

Mr khurram Shahzad

Mr khurram Khan

Country of Pakistan Punjab

City Gujranwala

Village Bujumal

Post office 52340

Zip code 3410158041265

Mobile phone number 00923127214048

00923464674502

My package parcel delivery Pakistan Punjab my home address