Earlier this week, my colleague Zach Strickland put out an intriguing article. There’s been “one transportation management trend that has stuck and not regressed” since the coronavirus and subsequent shipping boom ravaged supply chains. Just the one!

The change is hardly jaw-dropping. Tender lead times, which represent the amount of time from when a company requests truckload capacity to when that shipment is picked up, are up 10%-15% from pre-pandemic norms. This represents a whopping addition of 9.6 hours.

For all of the hullabaloo we saw over the past four years about the supply chain crisis, you’d think there would be a more seismic change. I decided to check in with some more supply chain experts in areas like lumber, automotive and medical.

Ultimately, the reason we’re no longer in a supply chain crisis isn’t that companies did anything particularly amazing to overhaul their manufacturing and distribution systems. Rather, we just started to slow down our buying from the peak of 2020 to 2021 — and corporations were able to catch up at last.

“I don’t think a lot has changed,” said Dustin Jalbert, senior economist of wood products at FastMarkets RISI. “I think a lot of people assume that there was a paradigm shift during the pandemic … . Structurally, nothing has really changed in the market from a supply standpoint.”

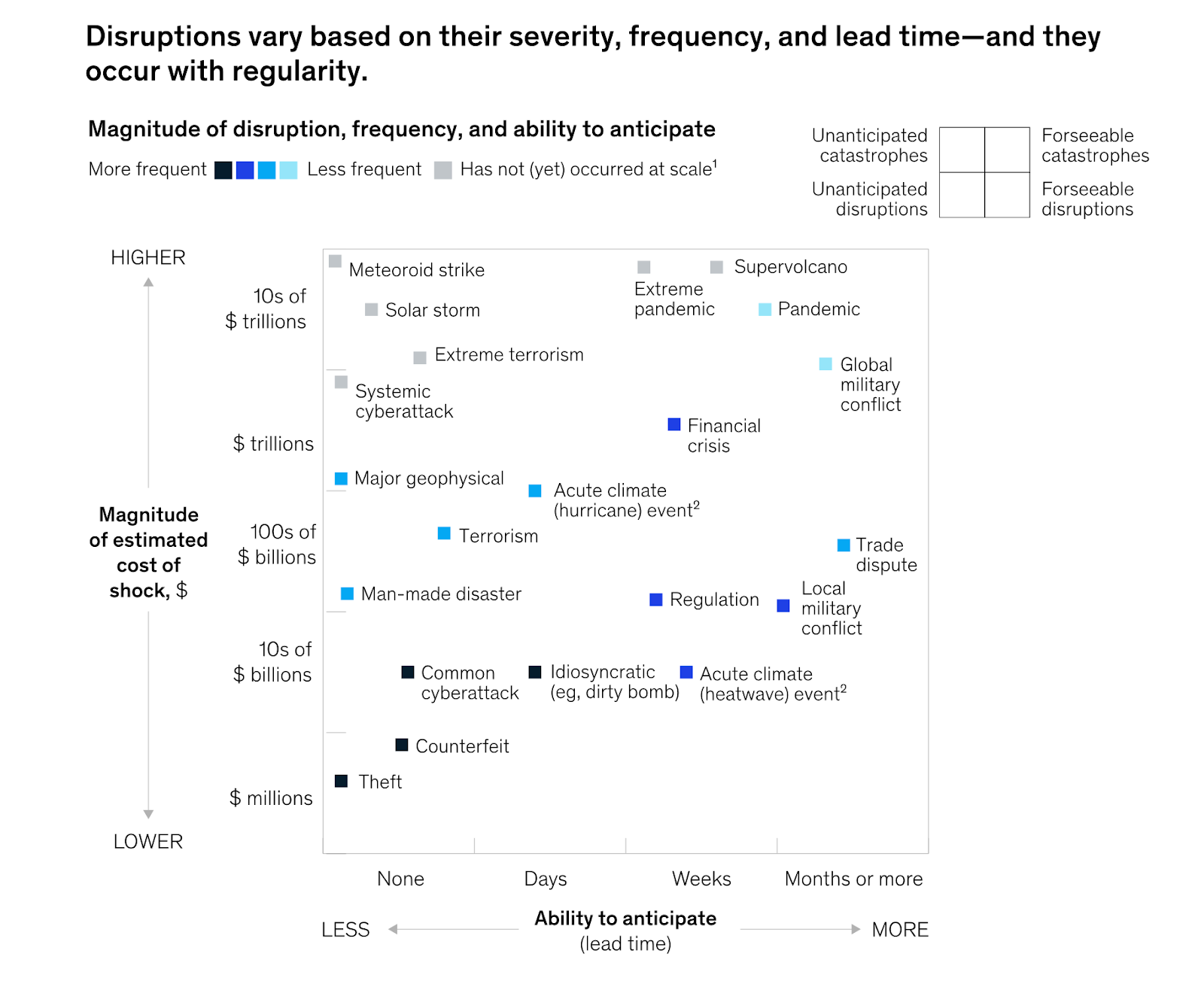

As a result, experts like Sandy Gosling, a partner in McKinsey’s Miami office, say we need to keep on our toes to prevent another “everything shortage.” The consultancy says a global military conflict, financial crisis, systemic cyberattack, extreme terrorism, supervolcano or (ugh) meteor strike could all disrupt supply chains … especially if companies refuse to keep them resilient. (On the other hand, in the case of a meteor strike, I will not be furious about delayed Amazon orders.)

“This means that companies will need to continue to be resilient, adapting as their supply chains evolve,” wrote Gosling in a response to emailed interview questions. “We believe that by applying a combination of resilience, agility, and sustainability, companies can future-proof their supply chains.”

It turns out there have been some changes in how we produce and move critical goods around the world. It’s just not the fundamental sweep you might expect. Here’s a quick summary of how our supply chains differ today from those halcyon, pre-pandemic days.

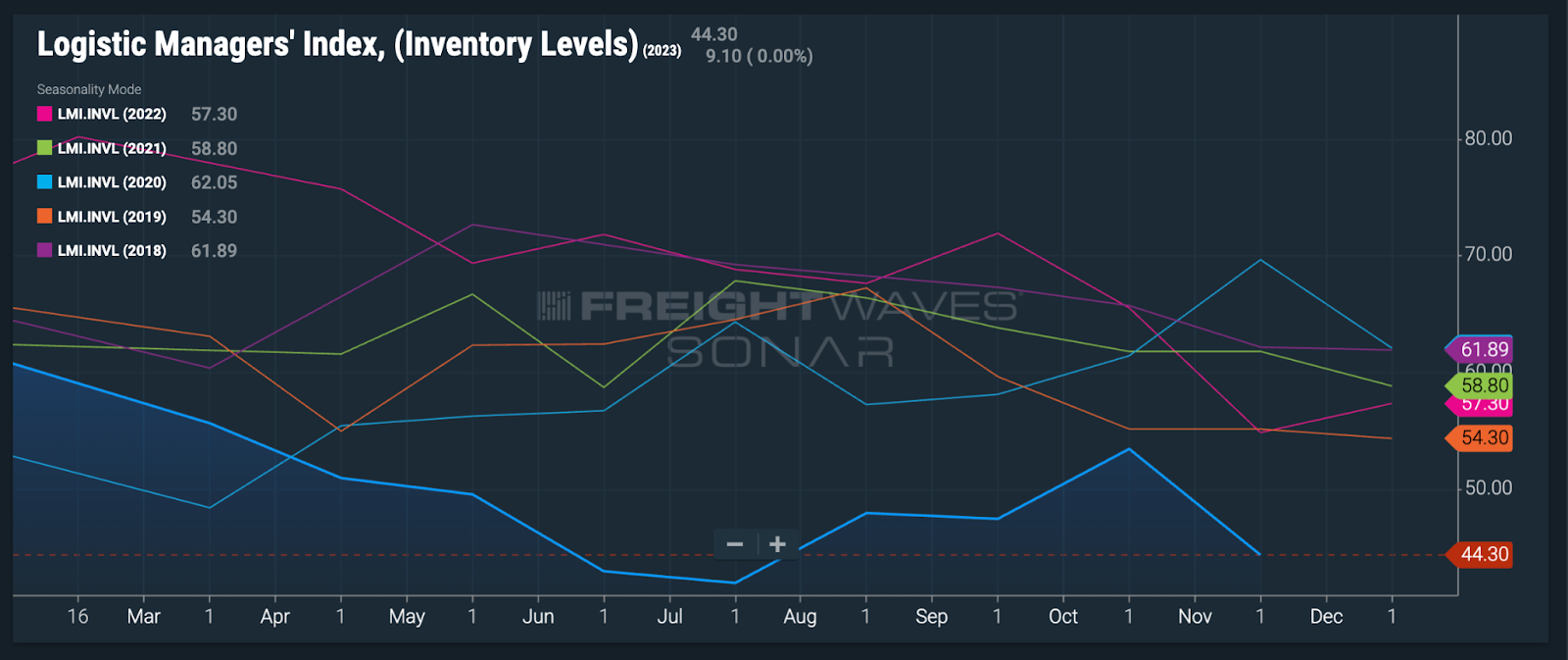

We went from minimal inventories to stockpiling to back to just-in-time

If you thought the coronavirus would kill off lean inventories, you’d be sorely mistaken.

“We are not seeing retailers/manufacturers embrace higher inventory,” Gosling wrote. “In fact, most of what we see being reported is inventory being right sized after many months of being too high. Of course, this varies by industry and will continue to remain an important trade-off for companies as they consider lead time due to source locations, cost to carry, and service levels to their customers.”

One key reason our delightful supply chains were so chaotic from 2020 to 2022 was the decades-long, corporate shift to embrace meager inventories and just-in-time production. One study found that American companies slashed their inventories by 2% each year from 1981 to 2000; that trend flourished through the 21st century as well. Leaner inventories have helped companies position themselves better to investors. They can appear to be producing the same amount of profit from fewer assets.

Of course, this is at the risk of having a stable foundation of goods should there be, say, a pandemic that shutters much of the world’s factories. In response, many companies started to stockpile inventories.

Hospitals did, too, according to Anne Snowdon, a professor at the University of Windsor in Canada who studies the health care supply chain. There’s just one issue: Whatever you’re stockpiling might be useless in a year.

“Stockpiles are good as long as the product stays fresh, meaning it doesn’t expire,” Snowdon told FreightWaves. “We know like any product they all expire over time.”

Or people might just not be very interested in buying whatever is in your stockpile. Retailers like Target, Best Buy and Lowe’s learned that lesson the hard way last year, when they amassed way too much inventory to avoid being caught without beloved items. Then, suddenly, customers stopped beloving those items.

Automotive might be the most classic example of just-in-time manufacturing — and the industry was one of the hardest-hit in the coronavirus crisis. According to Colorado State University professor Susan Golicic, it’s not likely that the industry will fully shake off just-in-time. But, it might look a little different.

“I think they’ll be looking at, What is the right amount of inventory to hold?” Golicic told FreightWaves. “They may still call it just in time, but the amount of safety stock that they’re holding might increase.”

We’re diversifying our supply chains, but there’s no mass exodus from manufacturing in China

Another commonly cited reason for global shortages and general supply chain chaos earlier this decade was our disaggregated supply chains. Where businesses may have manufactured every component of a finished product in one factory complex in the good ol’ days, it’s more likely that finished goods hold hundreds or thousands of components that are made all over the world. To add to the fun, many of these components are only made in one country or one region. That means any disruption to global shipping — or geopolitical conflict with those nations — would cut off American access to those key supplies.

As tensions heat up with China, more manufacturers are looking to relocate some plants to other countries. But it’s not as easy as it might seem. “Very few people are picking up factories and moving them,” one retail expert told Modern Retail in August. “It simply doesn’t work that way. It’s certainly not cost effective.”

What’s more, completely closing down shop in China or East Asia more generally doesn’t make sense given the massive population of consumers there, said Amy Broglin, supply chain strategy consultant and adjunct professor at Michigan State University.

“I don’t think most companies are looking to exit China completely,” Broglin said. “But I do think that being that heavily sourced in any place where you have an abundance of supply localized is not a solid strategy for continuity and introduces a ton of risk.”

The name of the game appears to be supply chain diversification. Some goods might come from China, others from Vietnam, and still others from Mexico or the United States.

“As a result, companies have been reevaluating their supply chains — not only by near-shoring, but also through regionalization as well, ensuring they have multiple sources of supply or multiple routes to take advantage of in case of disruption,” Gosling wrote.

In the world of medical, Snowdon said health systems have tried to reduce the cost of care by prioritizing ultra-low-cost supplies. That meant supplies typically came from low-wage countries. Now, procurement departments are thinking about buying supplies from a slew of regions.

Battery plants for electric vehicles may be one inroad for more U.S.-based manufacturing. Golicic said few plants currently exist to build these complex batteries and, as a result, automotive manufacturers are taking matters into their own hands. Ford is building plants in Michigan and Kentucky, while Toyota is investing $8 billion in an existing plant in North Carolina.

Perhaps we will see a return to the River Rouge plant yet. Such systems were probably less efficient, but they would likely weather the inevitable meteor strike with some aplomb.

What do you think of our meager changes in supply chain? Do you fear a meteor strike? Email rpremack@freightwaves.com with your thoughts. And be sure to subscribe to MODES for more.

Tom Miralia

A downside of free markets is the penchant for there to be a race toward overoptimization and brittleness. Once most the ‘fat’ is cut, next comes the cuts to diversification vis-a-vie ‘vendor convergence’, leveraging volumes, and extreme synchronization with JIT inventory levels. It’s just the way things work. Companies that work to maintain some ‘insurance’ by leaving some robustness in their supply chain find themselves losing market share over price to competitors and go-getters willing to ‘roll the dice’ in the short term. They’re typically playing with someone else’s money you know! For all the talk of resilience and sustainability, the reality is something different overall. And when the ‘world blows up’, everyone is in the same boat throwing up their hands and scurrying around dealing with the impact of that. Which is likely to cost, macroeconomically, a good bit more than the insurance cost of resiliency? If I had an answer for it all, I’d offer it!

Victor

There is an old adage that is always true……

What was once old will always be new……