The more popular it becomes to ship Asian containerized exports to the U.S. East Coast versus the West Coast – whether via the Panama or Suez Canal – the more hinterland transport demand shifts in favor of trucks hauling cargo westward at the expense of rail moving boxes eastward.

Evidence of the East Coast’s rising importance continues to build up on multiple fronts. In terms of shipping rates, the price to transport a container from China to the East Coast has held up better year-on-year than pricing to California. Consequently, the spread between those two rates is generally increasing.

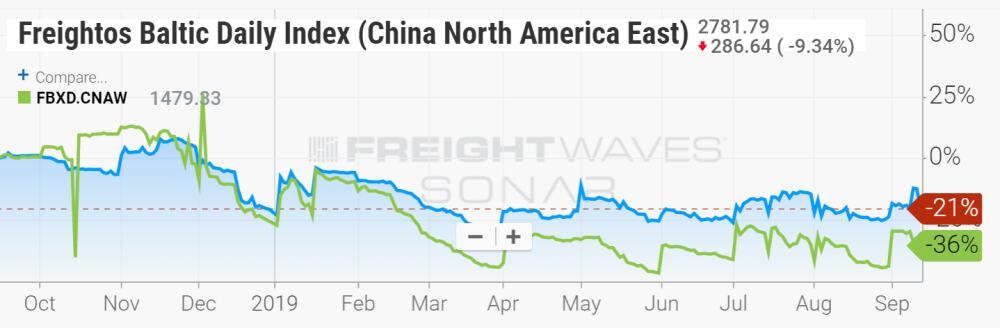

The price to transport a container per 40-foot-equivalent unit (FEU) is tracked by the Freightos daily indices. Assuming no major changes in vessel capacity, pricing trends can be used as a rough proxy for demand.

The Freightos index covering the China-East Coast route (SONAR: FBXD.CNAE) is down 21% year-on-year, whereas the index covering China-West Coast (SONAR: FBXD.CNAW) is down 36%.

Over a two-year period, pricing to the East Coast is up 17% and pricing to the West Coast is down 8%.

Widening Panama spread

The price of ocean shipping to the East Coast is obviously higher because the vessel must travel a significantly longer distance from Asia to get there versus Los Angeles/Long Beach. If the spread increases, it could be taken as evidence of increased demand for shipments to the East Coast as opposed to the West Coast.

The East-West spread, otherwise known as the “Panama spread” (SONAR: FBXD. PANA), has risen 74% over the past three years.

That said, the spread is still nowhere near levels seen in 2014-15, in the wake of labor unrest at West Coast ports. According to Henry Byers, ocean shipping market expert at FreightWaves, “In regards to the spread, it all goes back to the port labor strike [on the West Coast] in late 2014 and early 2015. Some importers got their teeth kicked in, with their vessels sitting off the coast for days and days.

“It caused an insane amount of congestion, and then, not long after that, the widening of the Panama Canal finally opened,” he recalled. The expanded locks debuted in June 2016; prior to that, container ships transiting the waterway had a maximum capacity of around 4,000-4,500 20-foot-equivalent [TEU] units, whereas the new locks allow for passage of 13,000-TEU vessels.

Following labor-action-induced congestion on the West Coast, “shippers were desperate to de-risk their supply chains by diversifying their routings of Los Angeles to the East Coast and move back inland via RIPI [reverse inland point intermodal]. That caused the greatest Panama spread in recorded history,” said Byers.

Events continued to move in favor of the East Coast in the years since. According to Byers, “The dredging of Savannah enabled the port to offer much more capacity, which was largely built around large BCOs [beneficial cargo owners] with large DCs [distribution centers] who had previously received freight via Los Angeles to Chicago, but were now incentivized to bring freight to the Southeast. They’ve been growing like wildfire ever since.

“You also have the fact that the Southeast – cities like Charlotte, Atlanta, Nashville, Chattanooga and Greenville – are attractive places for people to live, with a decent amount of jobs and fairly cheap living expenses,” he noted, pointing to how this has increased East Coast inbound cargo volumes.

“Then came the trade war,” continued Byers. “We have companies again getting crushed trying to stuff volume through Los Angeles and Long Beach. Some of the BCOs became tired of this scenario. U.S. importers are moving out of China to places like Vietnam, where smaller feeder vessels carry shipments to places like Singapore, where they can be transshipped to larger vessels.

“Geographically, it’s more economical to ship from places like Singapore and India via the Suez Canal,” he said, noting that the shift to Suez routes brings even more cargo to the East Coast.

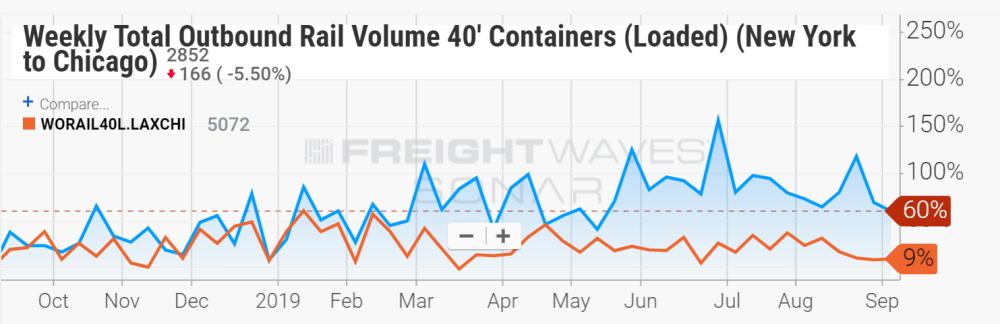

Yet another important point is that it’s not simply a case of East Coast trucking hauls replacing West Coast intermodal rail. At least to some extent, lost West Coast rail moves are being replaced by new East Coast rail moves. According to Byers, “We are also seeing a pickup of rail volumes inland from the East Coast to the Midwest.”

The volume of 40-foot containers moving from Elizabeth, NJ, to Chicago (SONAR: WORAIL40L.EWRCHI) has surged 60% year-on-year, far exceeding the 9% year-on-year growth in 40-foot container volumes from Los Angeles to Chicago (SONAR: WORAIL40L.LAXCHI).

Panama Canal container gains

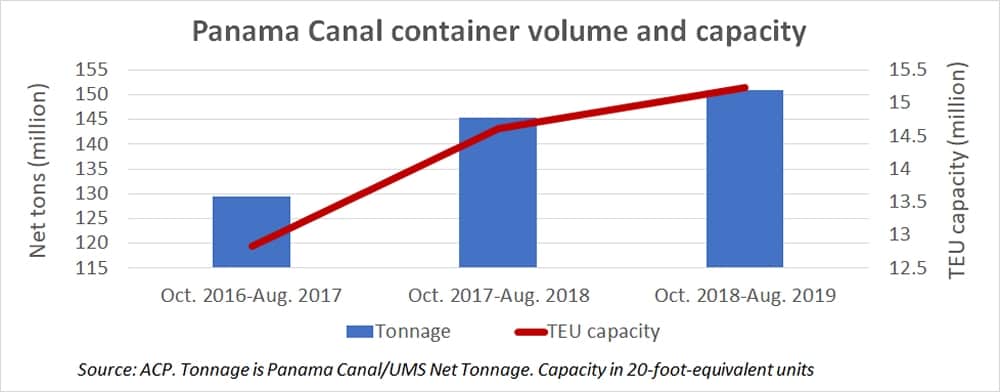

Another piece of evidence confirming the trend toward East Coast calls comes from the Panama Canal Authority (ACP). The higher the container volumes transiting, the more positive the indicator for East Coast ports, and by extension, U.S. trucking demand.

The ACP’s fiscal year runs through the end of September, so it has yet to report its fiscal-year performance. However, in response to a query from FreightWaves, the ACP provided its latest data on container-ship transits through August and for comparable period in the prior two years.

From October 2017 to August 2018, net tonnage carried aboard container ships rose 12.3% versus the same period the prior year and total capacity of transiting ships measured in TEU rose 13.9%. This period marked the initial surge following the debut of the expanded locks.

Over the most recent 11-month period, between October 2018 and August 2019, tonnage continued to increase, albeit more moderately, at 3.6%, and total TEU capacity rose a further 4.3%.

The ACP stats also confirm that the average capacity of container ships passing through the Panama Canal continues to escalate. This is important for the U.S. East Coast ports because rising vessel size decreases unit costs for carriers and renders the route more attractive.

The TEU/container-ship transit (including ships passing through both the old smaller locks and the new larger locks) was 5,633 in the period of October 2016 to August 2017, 6,120 in the following period and 6,475 in the most recent 11 months, equating to a three-year rise of 15%.

Can the Panama spread get too wide?

One of the key questions going forward is: Will there be a point when the Panama spread gets too wide? Is there a point where the pendulum starts swinging back to the West Coast if it gets too expensive to ship to the East Coast by sea?

This question has been raised given the imminent implementation of the IMO 2020 rule, which requires all ships not equipped with exhaust-gas scrubbers to use more expensive low-sulfur fuel starting Jan. 1.

Container lines have said that they will pass along the full cost of the fuel switch to shippers through a surcharge formula. That formula will include a distance factor, implying that if fuel costs spike, the Panama spread would increase significantly as a consequence of IMO 2020.

As previously reported by FreightWaves, there are valid arguments on why IMO 2020 would not have an immediate effect on the East Coast/West Coast volume mix even if fuel prices did surge.

Two other factors to consider are the longer-term history of the Panama spread and the price of low-sulfur distillate fuels.

As Buyers noted, West Coast labor issues pushed the spread out to unprecedented levels in early 2015. The difference between that historic spread and today’s can be seen by comparing the Drewry World Container Index Shanghai to Los Angeles (SONAR: WCI.SHALAX) to the index covering Shanghai to New York (SONAR: WCI.SHANYC). The spread back in early 2015 was triple what it is today. In other words, there could be a lot of breathing room left for the spread to increase before it forces cargo back to the West Coast.

In terms of fuel pricing, the International Energy Agency (IEA) came out with a report on Sept. 12 that pointed to a more optimistic scenario for fuel pricing in the wake of IMO 2020. According to the more positive scenario, distillate prices are being pressured downward by weaker global economic conditions and trade tensions, counterbalancing the effect of IMO 2020 increases – which could render the year-over-year increases in fuel costs much less onerous than previously predicted. More FreightWaves/American Shipper articles by Greg Miller

Editor’s note: Freightos has a business agreement with FreightWaves that includes editorial coverage.