The views expressed here are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of FreightWaves or its affiliates.

Where’s the strategic volume growth?

Just five years ago, in April 2014, BNSF expected to begin moving eggs and other perishables in unit trains with McKay TransCold as the lead organizer and customer. McKay was and is a third-party logistics service provider.

The “TransCold Express” was to move refrigerated or frozen consumer goods in a 50-railcar unit train between Wilmington, Illinois, and Selma, California.

There was great optimism for the planned service.

BNSF’s “TransCold Express” reefer service would operate dedicated weekly trains linking specially designed “food parks” in Wilmington (which is about 60 miles southwest of Chicago), with Selma (a town 20 miles south of Fresno). Each train was to initially operate on Wednesday and take four days to traverse the 1,800 miles between hubs.

From the Selma railhead, trucks would transload out of the railcars and deliver south to San Diego and as far north as the Bay Area.

Eastbound perishables out of California would be shipped from Illinois as far as 500 miles to locations in the Midwest, East and South.

The project had outside real estate investors to support the necessary terminal cold storage distribution. The Wilmington distribution center was called RidgePort and was developed by Ridge Property Trust. The Selma site was developed in part by Van-G Logistics.

There were two critical business assumptions:

- The 1,800-mile transit would take about 96 hours by rail (compared to about 84 hours by truck)

- Shippers would save up to 15% compared to shipping via truck

It didn’t work out.

What were the lessons learned?

There have been similar cold products rail service plans. But no clear business model to recapture the once-dominant railroad reefer role.

Yet there are some positives to try to build upon. The newest design of full-size boxcars (at just over 70-feet in length) is a big enhancement over previous boxcar designs.

After all, it can hold the equivalent of up to four modern 53-foot long trailers (or domestic 53-foot containers). How can a truck beat that?

Unfortunately, trucks are beating that. According to multiple independent sources, rail reefer transportation has (at best) between 2% and 4% market share of the longer distance (greater than 500 miles) movement of refrigerated goods.

However, that national statistic is misleading. Some California growers of certain commodities – like carrots – use rail to ship more than 25% of the crop (Surface Transportation Board data from about 2012). Other commodities like onions and broccoli drop to 6% or less shipped by rail. Overall, three counties in California’s Imperial Valley reported shipping about 9% of all crops by rail in 2013.

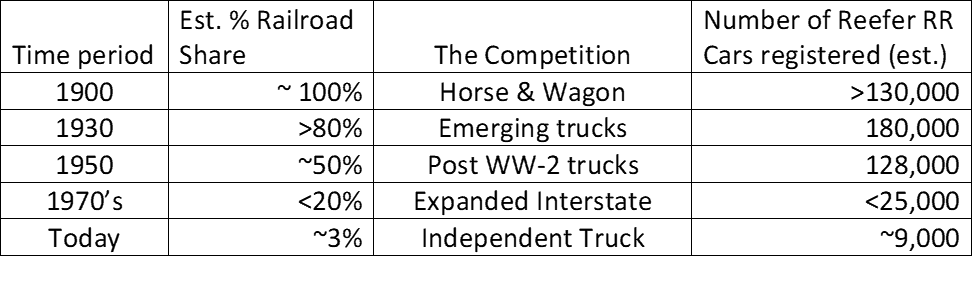

How does that compare with history? This table identifies the historic erosion of the railway perishable business.

(Photo credit: PictureArchives.net/Michael Palmieri)

When railroads were the primary transport mode, the volumes were huge. At its peak, the Pacific Fruit Exchange (PFE) railroad reefer company controlled almost 41,000 such ice cars.

Back in 1900, the United States was the only nation of its size that could distribute perishables across such vast distances as those between California and New York. Most of those perishables were shipped via railroads.

Then, trucks began appearing in greater numbers. Initially their reach was limited to a radius of about 50 miles. Why? There were few modern paved roads back then.

During World War II, the central transcontinental rail line of the old Southern Pacific and the Union Pacific moved as many as 800 to 1,200 reefer railcars daily out of California on that one route.

Following World War II, the die was cast; railroads lost market share to trucks. Rail market share losses accelerated. They even lost milk train business in the East. (Yes, milk trains were big revenue generators when I was a kid.)

The railroads – beset with multiple deferred maintenance problems and related financial issues – didn’t have a marketing and service answer to trucks.

Railroad engineers did come up with an innovative mechanical reefer design around 1947. Yet the older iced railcars remained the mainstay of the refrigerated railcar fleet through the 1960s.

Why? It wasn’t until 1972 that the last of the older refrigerated railcars that were cooled by ice were gone. This was about 120 years after their introduction.

And then the railroads did not turn to innovation and a re-capitalized reefer market entry didn’t occur.

By 1980, the Staggers Act allowed railroad companies a market exit strategy. But the legislation itself did not promote reefer innovation.

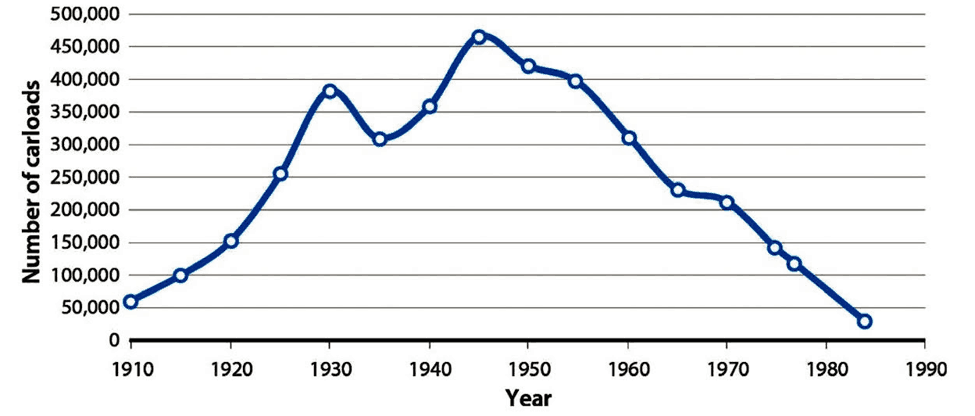

The following graph identifies the rise and fall of railroad refrigerated railcar service out of California. The plot is of PFE, one of the largest of the reefer car fleet owners.

There were two volume peaks – around 1930, and then 1945-47 peak. Within four decades, it became a niche business.

Some good news

There were several investments that signaled possible “pivots to re-growth.”

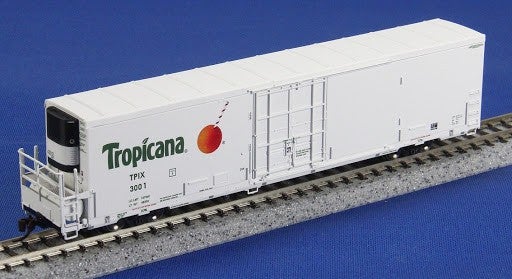

CSX and Tropicana invested in a fleet of mechanical carloads for a Florida to New Jersey orange juice unit train.

BNSF invested in about 700 new refrigerated boxcars in 2001. At the time, a headline read “first such investment in nearly 35 years” by that Class 1 railroad.

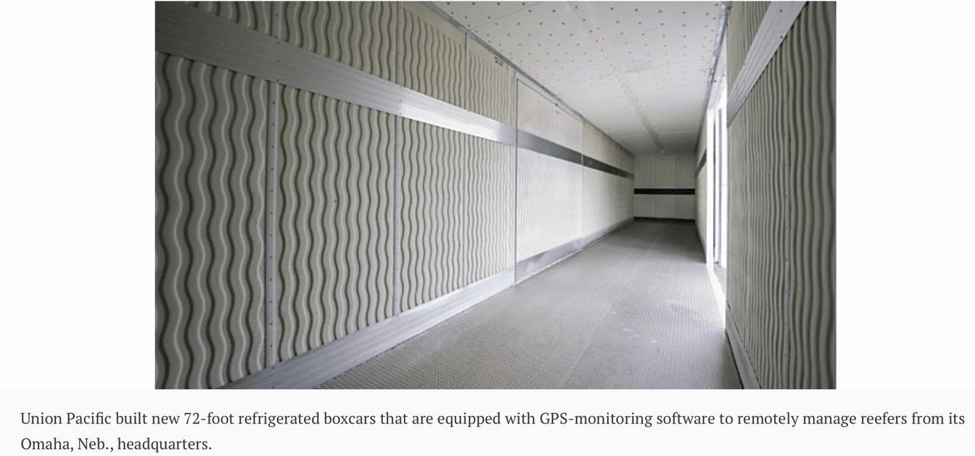

Looking good! Maybe? But those cars were essentially replacements for an aged fleet. It was more than a decade later in 2014 Union Pacific announced a significant reefer carload investment.

What about recent events? (2017-2020)

Union Pacific announced again in September 2018 that it would acquire 1,000 new high-tech refrigerated boxcars – and might later increase that to 1,600. Then, not much more about it.

There is another market plan. It is intermodal reefer focused.

Ted Prince and Tom Finkbinder at Tiger Cool Express (TCX) are proponents. They created their Tiger intermodal service back in 2014. Their business plan seized upon the benefits of two-high stacking of domestic 53-footer reefer containers.

They started small with only 200 containers. Then up to a 735-unit fleet. Next expanding towards 2,000 containers. Their economics are anchored upon:

- Volume commitment

- Consistency of reliable service delivery

- Year-round business volume

They see a niche advantage as truckers struggle with the regulatory hours of service issue. Prince calculates that mandatory truck electronic logging devices create an opportunity for railroads to gain a time of delivery advantage in certain reefer lanes.

Meanwhile, trucking continues to dominate the California Imperial Valley.

California grows about 80% of all fruits and vegetables in the U.S.

The winter harvest of celery, strawberries and lettuce is underway

The Fresno area generates about 80 daily truckloads of produce

Trucking spot rates this year remain low. That makes rail market penetration difficult unless railroads become more spot rate competitive. The truckers continue to offer service that takes mid-week harvested crops for next Monday morning delivery to buyers in Atlanta, Philadelphia and New York City.

It is not clear yet that the combination of selected precision scheduled railroading “lane demarketing” changes and some lowering of premium train speeds are winning back perishable customers.

There are conflicting market views. What are shippers seeing?

What amount of rail company capital must be invested towards perishable equipment? Will the railroads make that balance sheet investment? Or do third-party organizers have to step up?

It will be expensive. A refrigerated railcar costs close to $300,000.

When will we see the next large block of reefer intermodal or reefer railcars ordered?

To a strategic economist, these are the critical long-range predictive signs of growth versus no growth.

What’s your market outlook?

Acknowledgements:

- Ted Prince published documents and a report by Paul Scott Abbott (October 2017)

- “This Fascinating Railroad Business,” by Robert Selph Henry

- Selected reefer service reporting by Roy Blanchard from PFE data from: http://calag.ucanr.edu/Archive/?article=ca.2018a0036