There are important headwinds and tailwinds on the horizon that have yet to fully materialize.

Trucking markets are taking the coronavirus in stride — at least by some measures. Even as imports and intermodal volumes plunged in February and into March, contracted truckload volumes are up.

On a national basis, contracted truckload volumes (OTVI.USA) surged in the past week and are up more than 5% year-over-year. Capacity has tightened, too: Tender rejections are up slightly to 5.83%, breaking above the 5.5% level where they hovered through February. That’s still too loose to put upward pressure on spot rates, but it does mean that transportation providers are exercising a little more optionality.

That may be related to new awarded contracts that are coming online now at lower rates than last year, closing the spread between contract and spot rates. Shippers that now have access to lower contract rates are rotating freight out of spot markets to contracted carriers and pushing up contracted volumes relative to spot markets, testing routing guide compliance. So far, there’s been some pushback — rejection rates are up by 53 basis points — but not much.

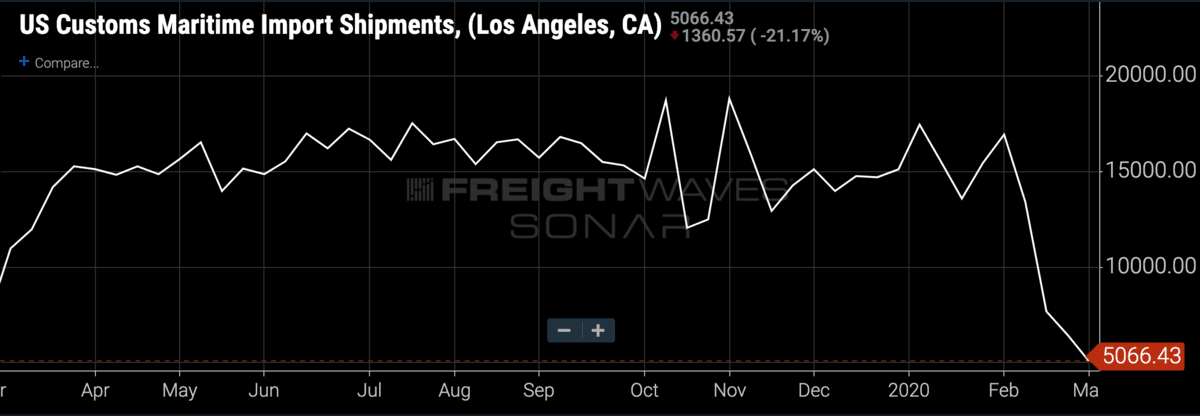

We have a good idea of the volume hitting West Coast ports and what’s underway on the ocean.

Eventually, lost Chinese imports will show up as a headwind to truckload volumes, but most shippers have ample inventories to run down before that happens. The total business inventories-to-sales ratio has been hovering around 1.4 months for the past two years or so, which is historically high compared to the five years prior to that period.

There is some evidence that those inventories will be depleted faster than usual. A freight broker we spoke to Thursday said that “shelves are emptying a lot faster than they usually do this time of year: Shippers are pumping canned food, packaged food and bottled water directly to stores.”

Stockouts are still a possibility in United States brick-and-mortar retail. Despite the Chinese government’s insistence that workers return to their jobs and reactivate the country’s massive production engine, there are reasons to believe that the economic recovery will take some time. Alternative datasets like containers waiting to be offloaded, coal consumption at power plants, and average road congestion in Chinese cities suggest that China’s economy faces a slow grind upward rather than a rapid “V-shaped” recovery.

The slow-grind-upward thesis still makes sense to us. After all, the reactivation of a massive manufacturing and transportation machine almost by definition occurs in an uncoordinated, piecemeal way. Raw materials suppliers, transport and logistics firms, and manufacturers are returning to work at different rates at varying capacities, and freight flows will bunch up at the weakest links in the supply chain.

Yet at this point, the coronavirus impact has yet to make itself felt across the broader over-the-road trucking industry, even though spot markets are already pricing in Los Angeles weakness by charging more to enter the market and less — as little as $1-$1.15 including fuel — to leave.

The American Association of Port Authorities has said U.S. port volumes could be down 20% in the first quarter; at some point, that has to make an impact on demand for trucking services. But if anything, at this point, consumers are buying at an accelerated pace in anticipation of quarantines or shortages which may or may not come, with the overall effect of boosting demand.

Stockton, California outbound volumes are up 36.2% month-over-month; Denver is up 31.9% m/m; Phoenix is up 26.9% during the same period, and Allentown, Pennsylvania is up 27%.

The other side of the market is supply. In a March 4 investor note, Morgan Stanley’s Ravi Shanker wrote about his meeting with Knight-Swift management. Knight-Swift (NYSE: KNX) said early results from the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration’s Drug & Alcohol Clearinghouse database were surprising: About 8% of tests resulted in failures, compared to the 1-2% rate they were expecting. If that failure rate holds through the spring and into summer, trucking carriers’ ability to find drivers will be constrained, and so, ultimately, will absolute trucking capacity.

“A continuation of this trend would likely have a severe impact on the marketplace,” Shanker wrote.

The Passport Research team’s Feb. 4 note on our capacity thesis outlines our belief that absolute capacity has been contracting for three quarters and will soon tighten relative capacity, assuming that freight demand (volumes) holds up. If the clearinghouse is removing drivers at quadruple the expected rate, market tightening could occur sooner, rather than later.

But like the coronavirus headwind, the capacity tailwind story has yet to play out.

Over the course of the next week, we’ll have a better understanding of how import shipments develop: If volumes stay lower for longer, it’s more likely that relative capacity loosens and spot rates get pulled down even further. We’ve already seen moves by Maersk that suggest China outbound container volumes will be weak for a while; the Danish steamship line raised rates from Northern Europe to China, effectively pricing it like a backhaul market.

The contraction in absolute capacity, from both the tough operating environment from truckers and the clearinghouse regulations, will take hold over a longer period of time. In our current framework for understanding absolute capacity, it typically takes three quarters of contraction before markets bottom, relative capacity tightens, rates rise and sentiment improves. In other words, over the next quarter or two, relative capacity will tighten assuming no demand-size shocks like a dormant China or coronavirus quarantines in the United States.

Right now the situation is still very fluid. Coronavirus cases outside of China are doubling every three days. Until the rate of growth in new infections slows in the United States, we think that caution will prevail over business investment and consumer spending, representing a potentially deep downside risk to freight volumes.

David S

This is a driver, a listener of your web seminar today (03/11) and thanks for addressing my question about buying a truck, which I still like to follow through with you for more info as there was no way to after the seminar ended.

This article touches up on what my initial inquiry needed answers: regarding freight markets and their effects by COVID-19.

Thanks again

DS