Zone-based congestion pricing for vehicles entering downtown business districts has long been considered a way to reduce delays and stress for commuters. But the potential for cutting fuel consumption and vehicle emissions now dovetails with the Biden administration’s climate policy goals — at a time when states are looking for ways to refill infrastructure budget coffers decimated by the pandemic.

If the new administration decides to put its weight behind the concept, how will truckers fare?

How it works

Congestion pricing “is a way of harnessing the power of the market to reduce the waste associated with traffic congestion,” according to the U.S. Federal Highway Administration (FHWA). It usually involves a tolling system that uses pricing to disincentivize travel during peak periods. The idea is to shift some rush-hour highway travel to other transportation modes, such as transit rail or bus, or to off-peak periods.

The country’s most populous metropolitan regions are also home to the largest congestion costs per mile for truckers (see table below). FHWA contends that by removing as little as 5% of the vehicles from a congested roadway, “pricing enables the system to flow much more efficiently, allowing more [vehicles] to move through the same physical space.”

Source: ATRI 2018

Congestion pricing is currently used on bridges, in tunnels and on stretches of interstate, such as in San Diego, Seattle and the Washington, D.C., region. But New York, San Francisco and Los Angeles are looking to take congestion pricing to another level by applying the fees to a cordoned central business district.

New York paves the way

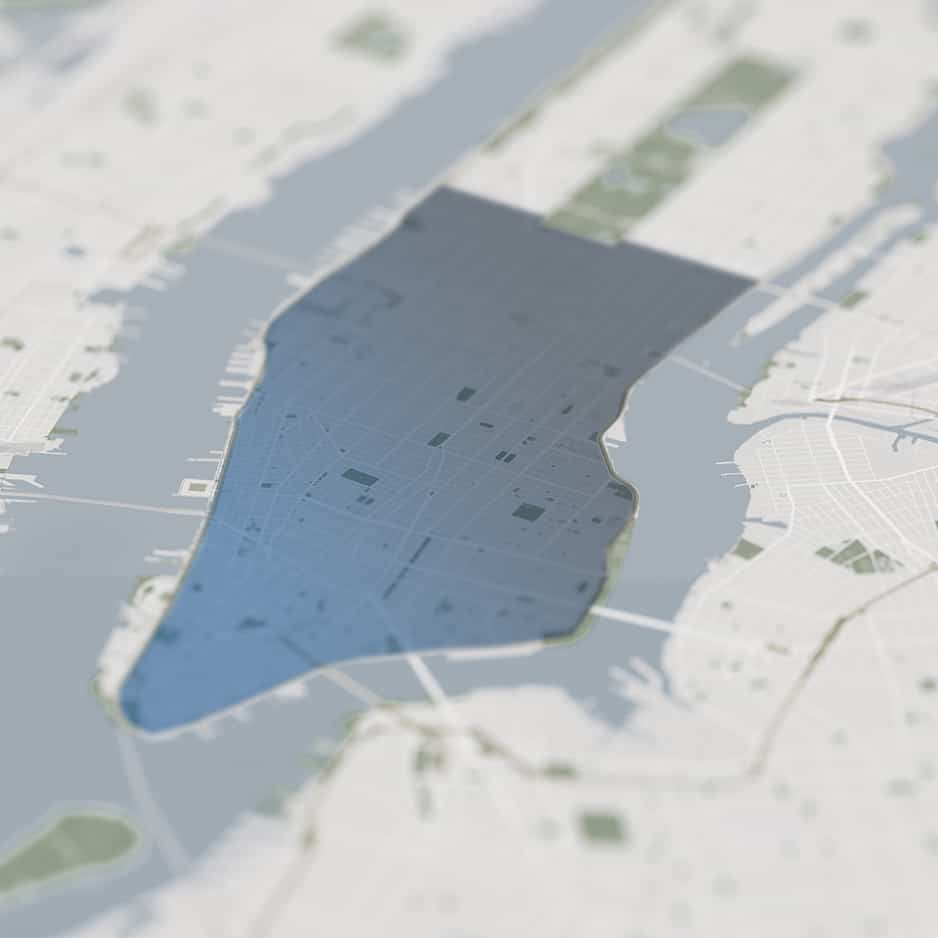

New York City was scheduled to become the first city in North America to install a central business district congestion pricing toll system when state lawmakers passed legislation in 2019. Fees for the proposal have not been officially set but were expected to be $11-$14 for cars and approximately $25 for trucks during prime business hours — less at night and on weekends, according to a report in The New York Times. Money generated from the toll would be used to fund the New York Metropolitan Transit Authority’s (MTA) Capital Plan.

However, the congestion program, which was initially planned to roll out this year, requires federal approval due to the involvement of federal funds. The approval never came under the Trump administration, stalling the program. But that could soon change under the Biden administration, which is attempting to align strategies that can pay for infrastructure while cutting pollution and greenhouse gas emissions.

“The Department [of Transportation] is making it a priority in the early days of this Administration to take a closer look at this topic so that we can give more guidance in a timely manner,” FHWA told FreightWaves in a statement.

Source: TransCore

“We are excited about the traction we see on congestion pricing with the new administration, and we see the news on the new infrastructure bill as a very positive sign for the transportation industry in general,” Clint Holley, senior vice president for Congestion Pricing Programs at TransCore, told FreightWaves. TransCore won the contract to build and install New York City’s tolling system.

“We are currently focused on the NYC implementation for NY MTA,” Holley added.

Building back productivity

Highway congestion threatens trucking productivity as well as the ability of shippers to deliver products. A 2018 study conducted by the American Transportation Research Institute (ATRI) found that traffic congestion on the U.S. highway system added nearly $75 billion in operational costs to the trucking industry in 2016. Nearly 1.2 billion hours of lost productivity equated to 425,533 commercial truck drivers sitting idle for a working year, ATRI found.

The potential for congestion pricing, therefore, “benefits drivers and businesses by reducing delays and stress, by increasing the predictability of trip times, and by allowing for more deliveries per hour for businesses,” according to FHWA.

ATRI Senior Vice President Dan Murray sees congestion pricing chiefly as a social engineering tool. “The goal is to price people out of rush hours to reduce congestion,” Murray told FreightWaves, “and it can raise a lot of money for the government.”

Unintended consequences

But Murray says congestion pricing systems also have unintended consequences — all of them bad.

Because even small added costs can make a big dent in truck drivers’ or carriers’ operations, they will tend to avoid congestion tolling, Murray argues. “The alternative roads are not engineered for heavy traffic, so it dramatically increases congestion on roadways that are not designed for heavy-duty trucks,” he said.

Regarding central business district congestion models like New York’s, “shippers and receivers — with the exception of restaurants that tend to be open later anyway — would have to be open at off hours or at night” to accommodate driver schedules. “They’re not interested in the extra costs of keeping staff there extra hours.”

Lewie Pugh, executive vice president of the Owner-Operator Independent Drivers Association, said that while larger distribution centers do tend to be open 24/7, businesses in a central business district, even the larger ones, likely will not.

“We understand the purpose of these plans; we all want clean air and less congestion, but the purpose is to get people into mass transit. You can’t do that with a load of corn flakes,” he said.

“Everyone assumes that we can pass those extra costs down, but it doesn’t work like that for us. You’re never going to pass the cost down, because in trucking there is always someone who will do it for less.”

San Francisco, Los Angeles next?

San Francisco and Los Angeles have their own central business district congestion pricing studies in the works and are closely monitoring developments in New York. The San Francisco County Transportation Authority is scheduled to issue final recommendations to its board in October. However, “assuming we move forward, it’s going to take at least three to five years to implement congestion pricing for downtown San Francisco,” a spokesman for the agency told FreightWaves.

Los Angeles launched its congestion pricing study in 2019 looking at four options, one of which includes a “Downtown L.A. Cordon.” If selected, the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority would have to approve the plan, which would then move to a pilot-project phase.

Related articles: