Digital freight network introduces novel product when shippers need it

Wednesday morning Seattle-based digital freight network Convoy announced that it has begun allowing shippers to designate any tendered truckload shipment — secondary, spot, etc. — as “drop-and-hook” and use Convoy Go’s network of power-only carriers and 3,000 trailers to move their goods.

Convoy’s drop-and-hook program, Convoy Go, began with early pilots in 2017. Two years later, Convoy Go scaled nationally with enterprise shippers. Now Convoy Go is available for any load from any shipper nationwide: When the shipper designates a load as drop-and-hook, Convoy’s transportation management system returns a rate based on market conditions. If the shipper accepts that rate, Convoy guarantees drop-and-hook service for that load.

“After we scaled nationally,” Convoy Chief Product Officer Ziad Ismail remembered in a conversation with FreightWaves, “the next problem became having a conversation with our customers: ‘We love working with you, but there’s all this freight that should have been drop, but it’s going live and hitting [the] spot [market].’”

Ismail’s example of a planned drop-and-hook load that fell off and was going to be rendered as a live spot load but for Convoy Go is admittedly only one way that a load could end up as drop-and-hook. What’s important is that the element of contingency and unpredictability that normally would have made drop-and-hook impossible is overcome by a combination of Convoy’s carrier network, trailer pool and technology.

“Is there a way to go after all the freight?” Ismail asked. “Not just the highly predictable loads?”

Ismail’s team ended up building the technology to power what could be one of the sophisticated drop-and-hook operations run by a 3PL.

Drop-and-hook loads involve tractors that pick up preloaded trailers, drop them off at their destinations, and often then reposition an empty trailer or pick up a new preloaded trailer.

Drop-and-hook operations make truckload carriers more productive by allowing them to utilize their assets more efficiently, and they give shippers greater flexibility in the scheduling of dock labor and the loading and unloading of freight. A drop-and-hook load is also less carbon-intensive than a live load because it eliminates hours of tractor idle time.

But drop-and-hook is more logistically complex, especially for third-party logistics providers and freight brokerages. First, it multiplies the number of assets: Instead of matching a load to a driver, a load must be matched to a driver and a trailer. Capacity itself is bifurcated and has to be managed separately — trailer pools need to be rebalanced across a network of yards based on expected supply and demand. Large gray trailer pools leased by the 3PL can represent significant fixed costs, and cash goes out the door even faster as more trailer repositions are required.

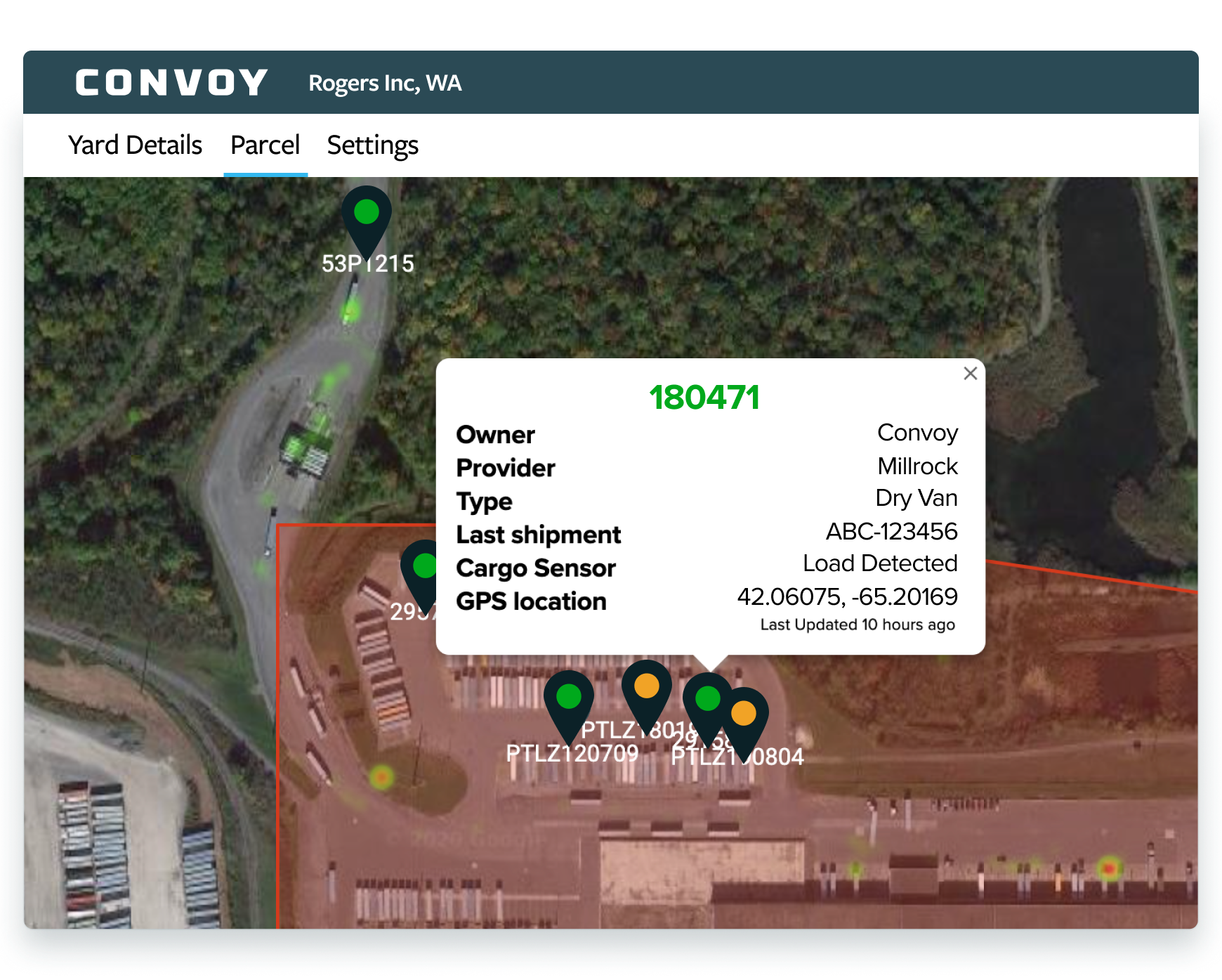

There are several scalable models for non-asset or asset-light drop-and-hook operations. Convoy Go relies on a suite of trailer sensors brought together by Convoy’s engineers. Rather than using a core trailer telematics provider, Convoy combined several different sensors, including GPS and loaded/empty sensors, and then built a back end to ingest and collate the data thrown off by the devices. Not only does that data include attributes like speed and direction updated every five minutes, but it also takes in qualitative data like driver surveys on the health of the trailer and photos of the trailer’s physical condition.

Convoy Go’s operations view alerts Convoy’s carrier teams when a trailer is deemed to be at risk of “going rogue,” for instance if it’s being pulled out of network, empty, with no carrier attached. That’s one case where Convoy’s automation alerts human workers that exceptions have occurred; another is when Convoy Go projects a deficit of trailers at one yard. If another trailer can’t easily be sourced, a human may intervene.

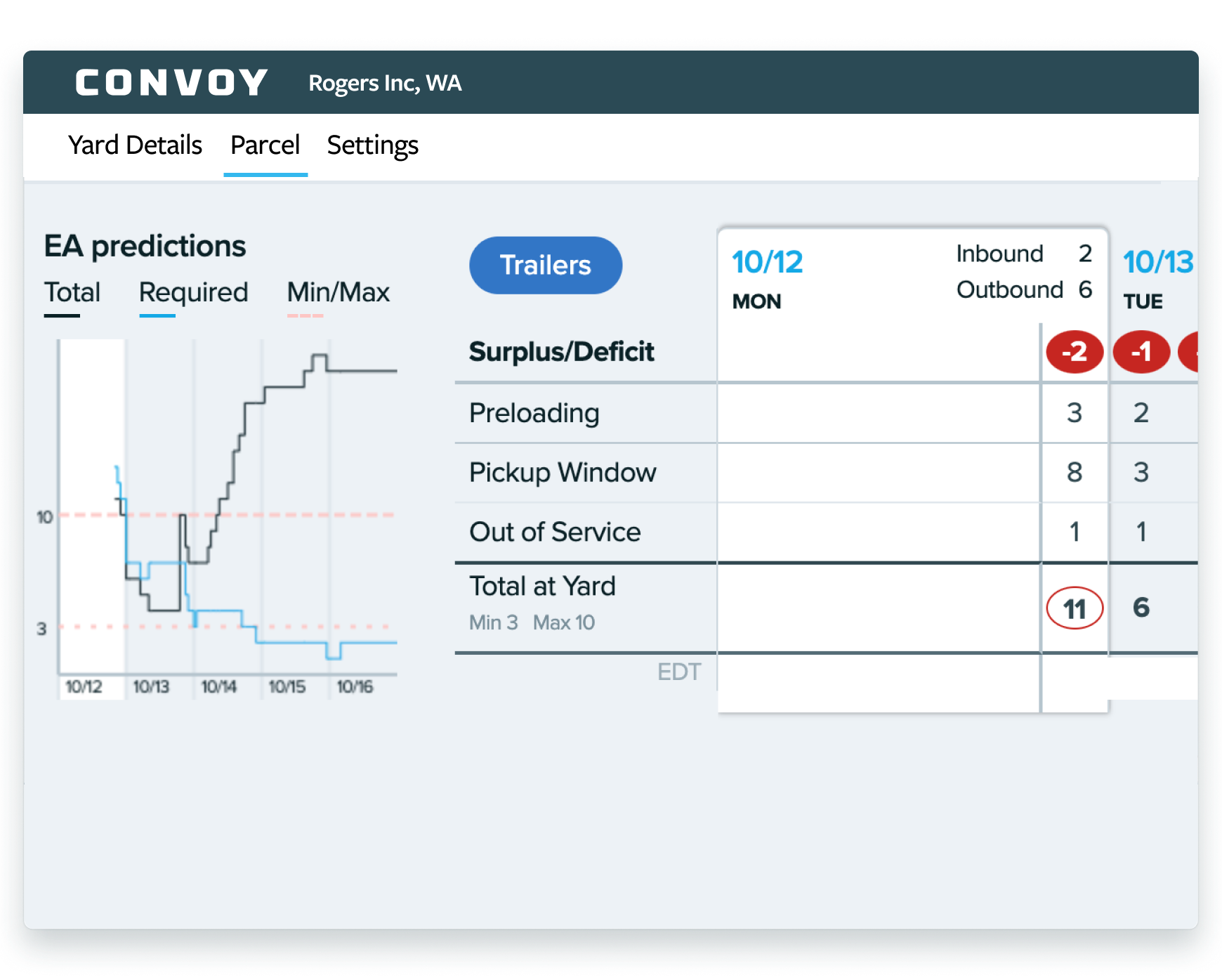

But the hardest parts of fulfilling drop-and-hook freight on demand are predicting where these loads will occur, deciding which trailer should be used for which individual load and dynamically positioning them in anticipation of demand. And at scale, those problems can only be solved by a powerful computer, and techniques for solving those problems at scale can really only be improved through the use of machine learning models. During a demo, Convoy displayed the number of permutations — combinations of possible drop-and-hook moves and repositions — its models crank through every day. It was a very large number: one followed by 2,000 zeroes.

Rylan Hawkins, principal engineering manager at Convoy, said that Convoy’s machine learning models predict how many trailers each of Convoy’s yards will need two weeks in advance.

“When there’s a deficit, it automatically finds the best trailer to route,” Hawkins said. Convoy’s network of trailer yards, all based at customer locations, is extensive, covering the entire country and concentrated in markets like Los Angeles, Seattle, Phoenix, Salt Lake City, Dallas, Houston, St. Louis, New York, Chicago, Atlanta and Lakeland, Florida. A count showed 13 yards in greater Los Angeles alone.

Ismail said that Convoy’s Automated Reloads technology, which creates roundtrips to offer carriers, filling their backhauls, also works with Convoy Go’s automated trailer routing to put together multileg moves for participating carriers and reposition its trailers.

Convoy did not reveal details about the unit economics of its trailer pool, but Hawkins did say that conventional metrics like trailer turns per week were too primitive for Convoy Go’s expanded operation, with its mix of local and regional moves. He said that Convoy “thinks more about the utilization of time” when measuring the efficiency of its routing technology.