For his entire life, Roy Walters managed bars and restaurants: upscale Italian eateries, dive bars and even strip clubs. Then, in March 2020, the pandemic shuttered his livelihood.

A truck driver buddy suggested that the newly unemployed Walters join him in the industry. So Walters drove an 18-wheeler around the country, seeing places like Seattle and the Grand Canyon, before he decided to own his own fleet. Today, the Clearwater, Florida, resident operates seven trucks.

Walters mostly stays at home, but sometimes he gets behind the wheel again. “For me, it’s almost like a vacation, except I get paid,” he said.

The trucking business has been burgeoning since he got into it. The pandemic sparked historic demand for durable goods, which is the kind of stuff Walters and his employees haul in their dry vans. But a maelstrom of inflation, rising diesel prices and overcapacity in the trucking market is sparking a sudden tumble of freight rates. “It’s been a struggle,” Walters said. “That’s for sure.”

The indicators are worrisome

Demand for freight has undeniably slowed. And, at FreightWaves, we believe a recession in trucking might be next.

Wednesday, the much-adored Cass Transportation Index Report declared that the freight market is in a slowdown, though the index’s experts said it’s too soon to declare a recession. Banks like Cowen and Bank of America have recently downgraded trucking stocks in their own notes to investors.

Dry van rates have tanked by 37% from Dec. 31, according to an April 8 transportation note by Bank of America analyst Ken Hoexter. Those rates are on the spot market – where loads are picked up on demand, rather than through a contract. The spot market is just a fraction of the trucking world, but spot numbers point to where contract rates will go.

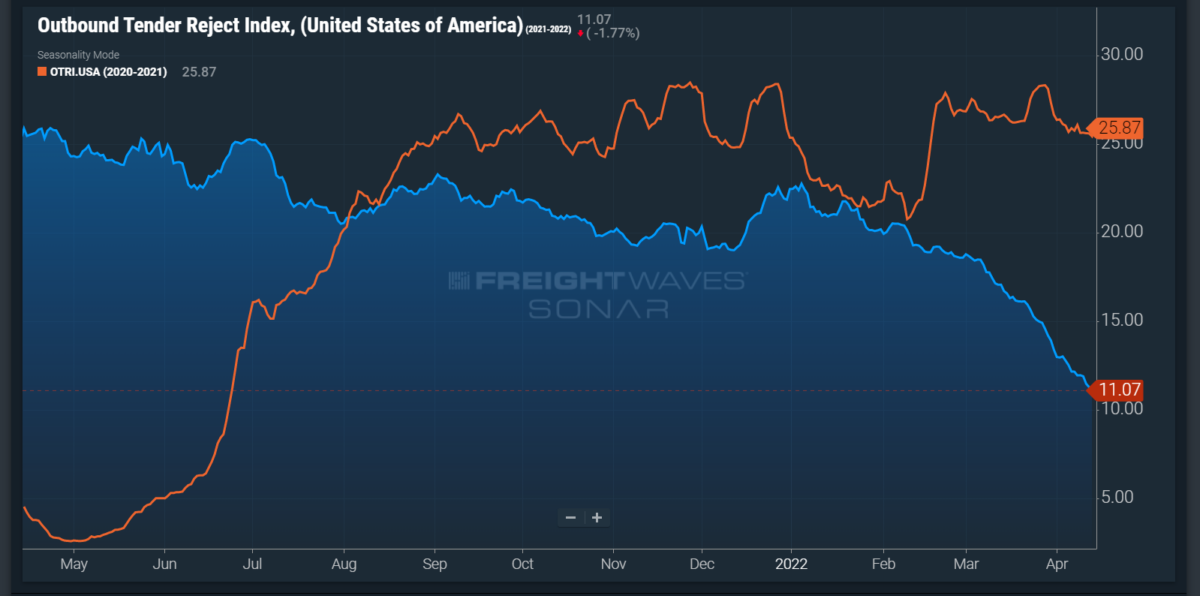

Another indicator of a downturn is the drop in contracted loads rejected by carriers. Contrary to the, um, idea of a contract, truckers can reject loads they previously agreed to carry. Usually, they reject a contract load if they can get a better job on the spot market. Analysts follow the outbound tender reject index to see if the trucking market is hot or not.

Compared to last year, the market is decidedly not. Only 11% of loads are getting rejected right now, way down from 25% at this time last year.

Through the end of 2020 and throughout 2021, trucking was “white-hot,” said Amit Mehrotra, managing director of transportation and shipping research at Deutsche Bank. As Avery Vise of FTR Transportation Intelligence told The Wall Street Journal on Wednesday, trucking companies could expect to simply “print money” amid this market.

Now, truck drivers who have entered this industry in recent months are scrambling to stay profitable – and some have already stopped driving.

What happened?

Demand for random crap softening amid influx of driving capacity

If your high school economics education was as prestigious as mine, you know that high supply or low demand leads to decreased prices. Right now, there’s both an increase of supply (truck drivers) and decrease of demand (loads for drivers to move).

The supply of truckers is way up. Thousands of new fleets are registered each month in the U.S., and it’s reached a fever pitch in recent months. In February alone, a record 20,166 trucking companies entered the market. (Keep in mind, the typical trucking company is very small; 89% have one to five trucks.)

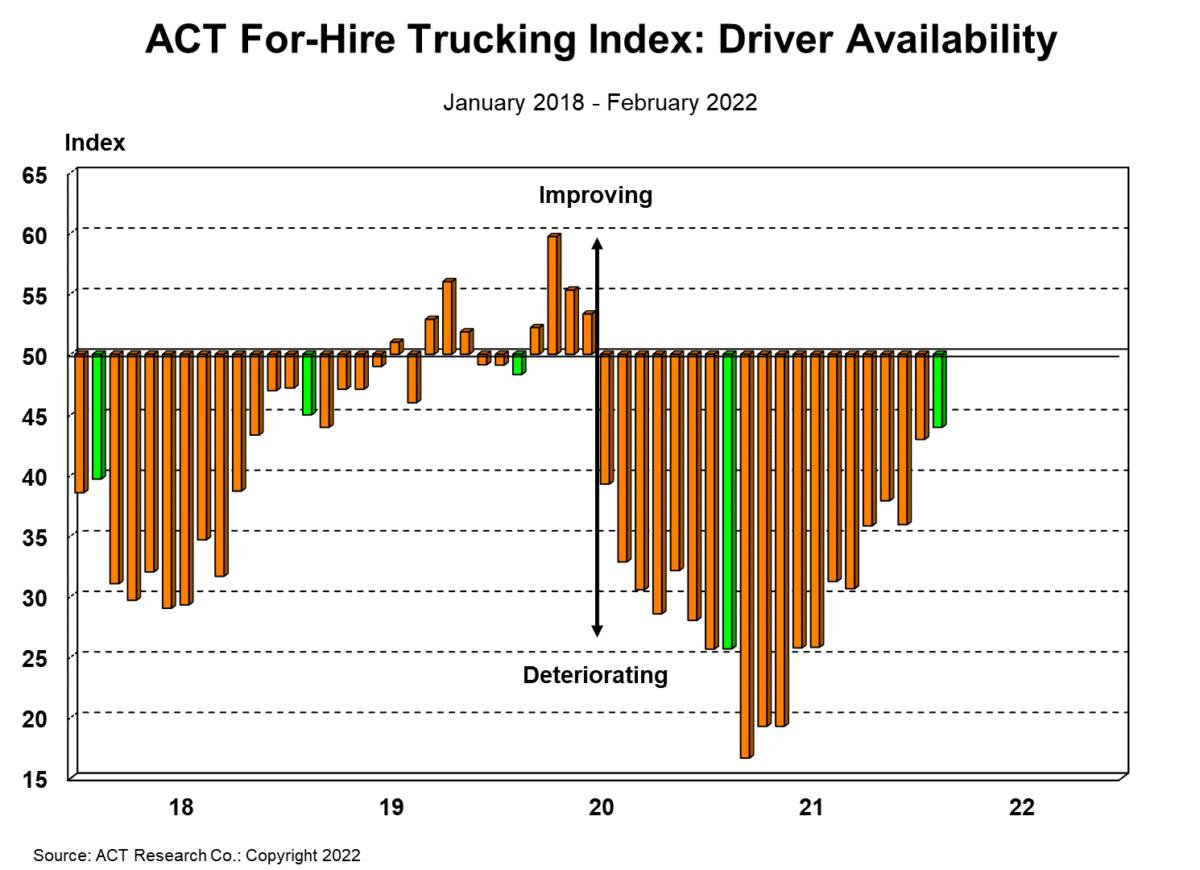

The labor market for truckers was unusually tight through the end of 2020 and throughout 2021 , but an ACT Research survey of trucking companies shows that driver availability has been improving. Mehrotra told me workers have finally depleted the savings they built up during the pandemic and are returning to work.

Meanwhile, demand for truckers has softened. Consumers are slashing their spending – particularly when it comes to buying more and more stuff. Core retail sales fell by 1.2% in February, the most recent number available from the feds. Those sales will likely continue to soften. In response to historic inflation, 84% of Americans surveyed by Bloomberg News said they would cut back spending. Some have already been forced to cut back, according to a CNBC poll.

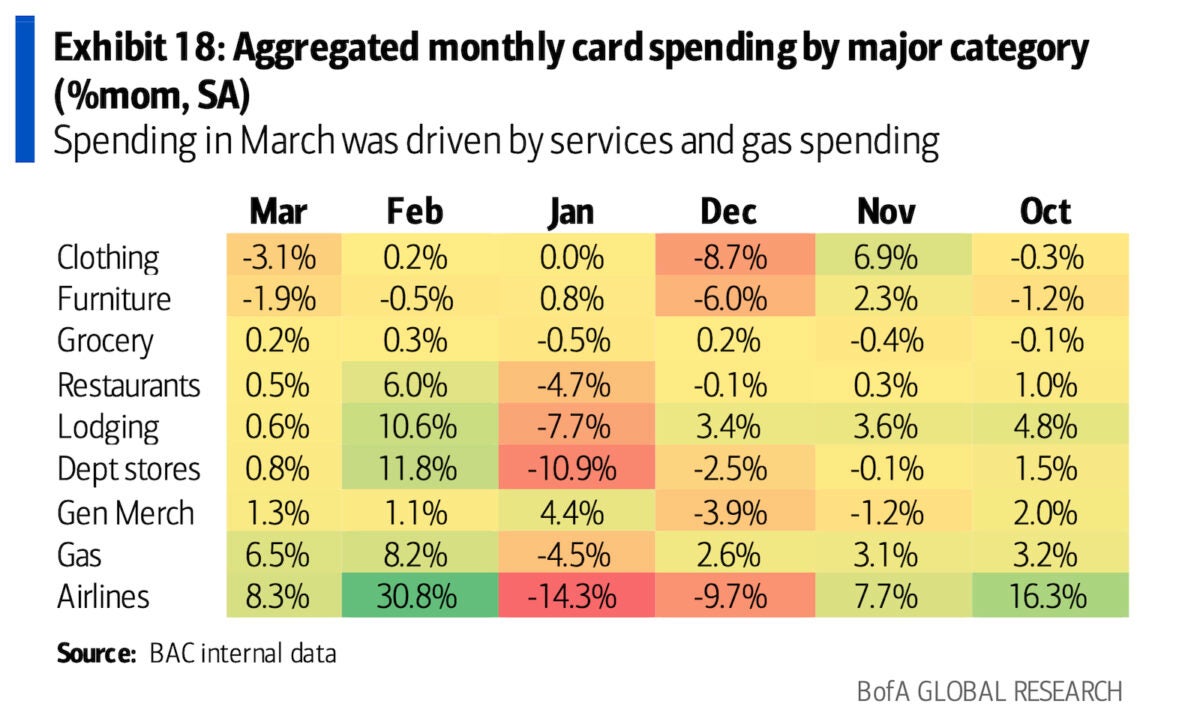

And those who are still spending are increasingly going to restaurants and concerts instead of, say, buying lots of stuff from Amazon. The latter requires far more truck drivers than the former. See this study from Bank of America economist Anna Zhou:

There are lots of truck drivers who entered the industry when our only hobby was online shopping. But, amid inflationary pressures and a society that’s mostly reopened, consumers are buying less of those durable goods. It’s an overlap of the Venn diagram that might result in a lot of new fleets being flushed right back out of the market.

I’ll let Walters explain:

“With rates being so high, everyone and their uncle bought a truck. I wish that it had a little more stability for the drivers and the small carriers. With more trucks on the market, the shippers and brokers can kind of dictate the price – because somebody is going to take the freight.”

Return of the bloodbath?

This normalization in trucking shouldn’t come as a surprise, Mehrotra said. “It’s totally reasonable to assume the white-hot demand environment we’ve been in the past two years is going to moderate,” he told me.

Still, the plummeting freight rates are stressing out the many, many new truck drivers who started their own fleets or entered this industry in the past two years. Their experience of running a trucking business has been in an unusually favorable market. Some might not have previous experience running a business. So the plummeting rates, coupled with the spike in diesel, are a slap in the face.

It’s all reminiscent of the 2019 trucking bloodbath (which I wrote about quite a bit at my old gig at Business Insider). In 2018, trucking was booming. Drivers were receiving record-high raises amid a capacity shortage that year. Many joined the industry. Unfortunately, demand for trucking services sank at the same time. That’s a very short explanation for why 1,100 trucking companies went out of business in one year.

Despite this history, some drivers aren’t worried. Travis Ludi, who is based outside of Oklahoma City, has been a truck driver for 10 years. He opened his own trucking authority just one and a half months ago. He said his realm of trucking – hauling grain for animal feed – is much steadier than the dry van world. (There is one downside to this recession-proof sector, however. Ludi also hauls the “left remnants” of kill plants to pet food factories, which he confirmed to me does not smell good!)

“A lot of companies or other owner-operators get in over their heads as the rates go up,” Ludi said. “They’re buying brand new trucks at higher prices due to inflation. Whenever rates go down to a normal level, they have to go out of business.”

Others are feeling more cautious. David Guzman in San Antonio has already parked some of his trucks.

Guzman bought three “dirt cheap” trucks from a liquidation company in early 2020. It turned out, those trucks were previously owned by Celadon, a company that pulled in $1 billion in revenue before filing for bankruptcy amid the 2019 trucking bloodbath.

When diesel started to spike this year, Guzman ran the numbers and realized he wouldn’t be able to run those trucks. He has a separate fleet that runs Amazon loads and has his equipment paid off, which is helping make ends meet. “I can’t imagine what folks that have payments on their equipment are going through right now,” he said. “The way the rates are, you have to run twice as hard to make ends meet. I can’t help but feel for my fellow truck drivers.”

In the meantime, it’s another bloodbath that these Celadon trucks might be sitting out.

Thanks for reading! You can reach out to the author at rpremack@freightwaves.com or rpremack@protonmail.net. Subscribe to the next edition of MODES here.