Each week, Paul Kenyon logs onto his computer, places his weekly grocery order from Walmart, and clicks the “pick up in store” option. A few days later, he drives to his nearest Rhode Island Walmart — about 8 miles away — and collects his order.

It is a routine he picked up at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic as a way to social distance. But Kenyon, who is retired, is an outlier. He lives in a suburban community and is generally older than the typical customer choosing an alternate pickup location for his online order.

Recent research suggests that customers picking up their items at alternate locations tend to skew younger, so it is the ability of providers to reach people like Kenyon that could determine how widespread the future of alternative delivery locations (ADLs) become.

ADL’s role in e-commerce

New research from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute has shed some light on the concept of alternative delivery locations (ADL) and whether it is an approach that will be supported by e-commerce customers.

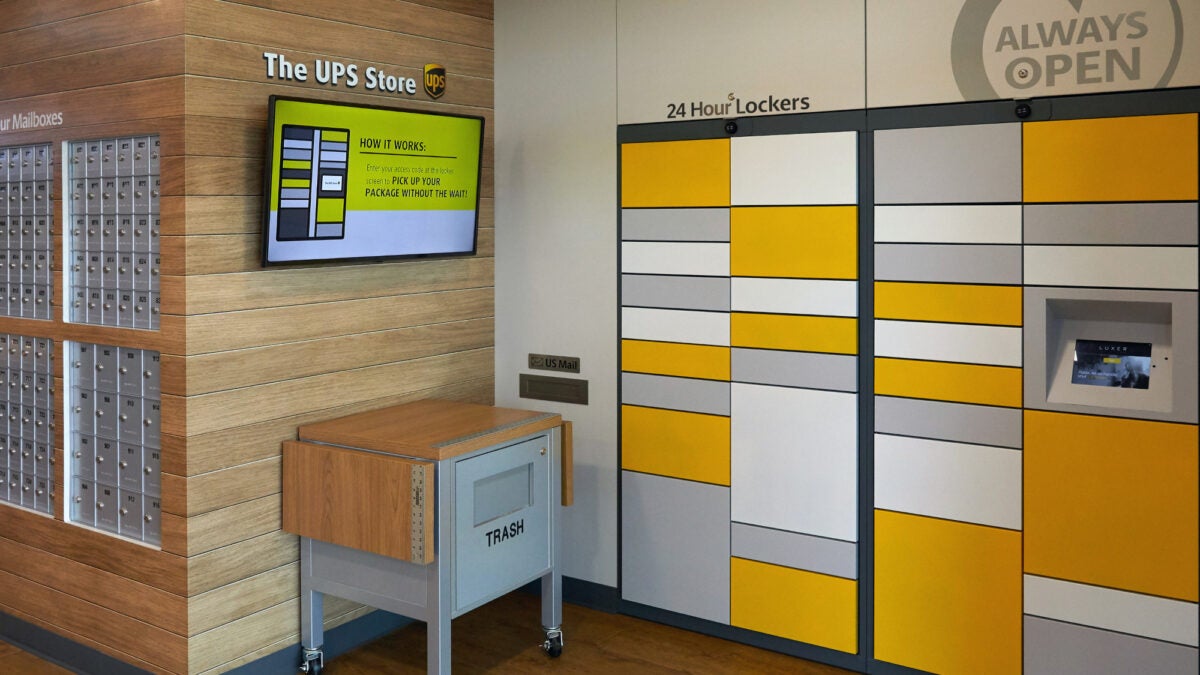

The concept of ADL is that a delivery provider is able to drop multiple packages in a single location — think an Amazon Locker, retail store location or even a mini warehouse or storefront on a busy city street — and the customer will come to that location to pick up their item.

It reduces fuel usage, lessens congestion and can potentially lower the end consumer’s cost of goods. And it can be particularly useful to pure-play e-commerce merchants without physical store locations, helping drive down shipping costs.

But it is not widely used in the U.S. — yet.

“There is a target group of frequent online shoppers that is more of a burden to the freight system and the environment overall,” Cara Wang, an associated professor in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute said in a press release. “Through new technology or developing incentives, cities need to find a way to encourage communities to understand the benefits of ADLs.”

Wang, along with doctoral student Woojung Kim, recently published research looking at mobility data in New York City and how that translates to ADL in the region.

“It’s clear from the data that because different populations use ADLs differently, transportation planners cannot implement a one-size-fits-all solution to every neighborhood, every city,” Wang said. “We are a long way from finding all the answers, but results from this research can help policymakers in dense urban areas better establish strategies regarding the ADLs as a way to mitigate negative externalities generated by delivery vehicles.”

The paper, “The adoption of alternative delivery locations in New York City: Who and how far,” was recently published in Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice. The authors claim it is the first study to comprehensively investigate behaviors on the ADL from the users’ perspective, but it is just one in a series of papers on last-mile delivery that Wang is exploring, she told Modern Shipper.

Only in my neighborhood

Wang said her team is looking at a number of last-mile delivery options, including crowdsourced deliveries and consolidated deliveries. The ADL paper, though, identified some clear demographic trends to users.

Using advanced computer modeling to review data inside the New York City 2018 Department of Transportation Citywide Mobility Survey database, the authors found that people who receive more packages are among the least likely to use ADLs. Conversely, those who are younger and those with higher incomes were more likely to utilize ADLs. It also concluded that older populations would use the service, but generally only if it was available within a two-block radius of their residence.

“ADL works in some cases, but not others, and we wanted to know how and why and where,” Wang said. “From there, we looked into people’s willingness to use ADL, and at least based on [some data] there is a clear difference” among demographics.

“In general, midtown Manhattan has a higher probability for those using alternative delivery, but it has to be located within a short distance of their residence,” Wang added. “In the downtown area, [people] can accept relatively longer distances” to retrieve their packages.

Wang said the research looked at a number of data points, including gender, age, occupation, income level, order volume, and how often people used their smartphones.

“In the end, most of these factors did not seem to be as important as age and occupation,” she said.

ADL’s inconvenience

Satish Jindel, an expert in last-mile and parcel deliveries and president of SJ Consulting, questioned the underlying conclusions the authors arrived at, telling Modern Shipper that it doesn’t make a lot of sense as to why Americans who can have the convenience of an item delivered to their homes would generally choose to have it shipped somewhere else.

Shippers and retailers, though, are looking at ways to reduce shipping costs related to e-commerce. Part of that is an effort to get more people to look at buy-online, pick-up-in-store (BOPIS) options. Alternatively, there are efforts to shift to a buy-online, pick-up-anywhere (BOPA) option.

Well, in European countries, alternative shipping options are not just prominent but, in some cases, dominating choice, receiving up to 70% of deliveries. I have a friend in Denmark getting nine out of 10 of his parcels to other than home delivery locations due to convenience and price benefits. So the only real question is how fast the U.S. will follow some EU trends.

Mitchell nikitin, co-founder of via.delivery

That’s what Via.Delivery is trying to do, hoping to replicate a model in North America that it said is popular in Europe. In February, Via.Delivery released its first BOPA Index, which found that 18% of U.S. online shoppers choose BOPA when offered that choice at checkout, and 50% of those using BOPA saved money on shipping when compared to residential shipping options.

“Buy online, pick up anywhere solves pressing challenges that arose during the pandemic and subsequent supply chain issues,” Mitchell Nikitin, CEO and co-founder of Via.Delivery, told Modern Shipper in February. “At a time when residential shipping can cost 30% more than shipping to a commercial address, BOPA offers a lower-cost alternative while also providing consumers the ability to ship packages anywhere for convenient pickup.”

BOPA delivers cost savings

Via.Delivery found that 50% of those choosing BOPA do so for the cost savings, while 15% cited added security and 15% named convenient delivery as reasons for choosing the option. Another 15% said they used BOPA as a way to keep gifts a secret.

While many may not be aware of alternative delivery locations, the BOPA Index found that 93% of Americans currently live within a 5-mile radius of a BOPA location, and 54% live within 1 mile. This includes Amazon Lockers, which can be found in many locations including places like 7-Eleven stores.

UPS (NYSE: UPS) has offered its Access Point network for several years. The company now offers approximately 21,000 Access Point locations in the U.S. and more than 52,000 globally, all designed to offer more convenience for customers and lower costs for brands.

The package giant points to benefits for retailers as well, noting that Access Points bring customers into physical locations. UPS, which has Access Points in major retailers including CVS, Michaels, Advance Auto Parts and of course The UPS Store, said 90% of U.S. consumers are located within 5 miles of a location.

Following European trends

Nikitin believes BOPA will become a viable option in the U.S.

“Well, in European countries, alternative shipping options are not just prominent but, in some cases, dominating choice, receiving up to 70% of deliveries,” he told Modern Shipper. “I have a friend in Denmark getting nine out of 10 of his parcels to other than home delivery locations due to convenience and price benefits. So the only real question is how fast the U.S. will follow some EU trends.”

While BOPIS and BOPA are different animals in many ways, the essence is the same: Entice the consumer to make an effort to retrieve the items and therefore lower logistics costs for the brand/shipper. Nikitin said Via.Delivery’s research suggests BOPIS is penetrating as much as 45% of online orders for omnichannel retailers, citing Target as a good example of a brand that has achieved a balance.

Watch: Last-mile delivery in an omnichannel world

“Alternative delivery location is not precisely BOPIS, but the user experience of buying online and picking it up somewhere else is already marching through the U.S. retail,” he said.

For BOPA to catch on, Nikitin said brands need to help lead the charge through education and incentives. Highlighting the sustainable aspect of alternative delivery — local pickup can reduce CO2 emissions by up to 40%, Nikitin said — at checkout may encourage some consumers. Others may be enticed by lowering the threshold for free delivery from $35 to $20 for instance, if that delivery is to an alternative delivery location.

Is there a rural BOPA opportunity?

While the RPI study looked just at New York City data and Wang said it is believed that alternative delivery locations may work best in dense urban areas, Nikitin said brands should not abandon the idea of rural sites entirely.

“You are right that rural areas are more challenging for BOPA due to a decrease in the proximity of pickup locations,” he said. “At the same time, some rural areas tend to have lower incomes. Thus, delivery price tag becomes even more important.

“The best strategy generally is to be where customers are going anyway as a part of their lifestyle: gas stations, pharmacies, convenience and grocery stores,” Nikitin added. “These locations do not generate extra pickup trips as part of the daily (or at least weekly) routine. That is why increased distance is considered to be less problematic.”

What is clear is that BOPA and BOPIS are just emerging as delivery options, but brands, shippers and delivery partners are critical links to making them work. As costs rise, more vehicle stops result not only in higher delivery costs, but also an environmental toll. EcoCart, which offers environmentally friendly shipping options for e-commerce brands, said that last-mile delivery growth will increase carbon emissions by 30% from present-day levels by 2030.

The combination can be attractive to providers looking for ways to minimize both impacts. Nikitin said to attain these goals, merchants are going to need to be creative.

“As brands benefit from reduced shipping rates and reduced porch piracy losses, extra discounts or coupons for subsequent purchases may be used as another way to encourage the use of BOPA,” Nikitin said. “This approach may often even increase overall long-term value, increasing the average number of orders per client.”

Merchants that find success with ADL may find more Kenyons in their future.

Click for more articles by Brian Straight.

You may also like:

Drones are flying into weather data deserts. Can they be stopped?

Navigating COVID-19 shipping chaos: Finding capacity and servicing the customer