Some recent rains in the basins that ultimately dump water into the Mississippi are a start, but the barge shipping problems that have created enormous backups on the river, particularly near Memphis, Tennessee, remain a long way from resolution.

“Current water levels are the lowest we have seen in recent years and in some locations have reached or surpassed historic low-water levels set as far back as 1988,” a Coast Guard spokesman said in an email to FreightWaves on Monday. “These conditions have created significant navigation hazards to the Marine Transportation System.”

In that email, the Coast Guard official said the Mississippi is closed to traffic at mile-marker 676-686 near Battle Axe/Tunica, Mississippi, where there is a queue of 66 vessels and 1,055 barges headed northbound and 23 vessels and 24 barges southbound. The vessels would be a tug or other power unit that would push a lineup of barges.

The Coast Guard also said there is a closure near Memphis that has a queue of three vessels and 39 barges northbound and a much larger group of 51 vessels and 710 barges southbound.

To put that in perspective, Mike Steenhoek, the executive director of the Soy Transportation Coalition (STC), described the number as “phenomenal.”

Steenhoek said while the levels at Memphis receive most of the attention because it is a key city on the Mississippi, the entire river south of St. Louis is having backups.

Water levels through the river south of St. Louis are being measured in negative numbers. That does not mean there is less than zero water.

As the National Weather Service for Pennsylvania explained in a post, all rivers are given a “zero level” of a certain depth that varies depending on location and history. They are changed infrequently.

“A river’s stage at a point (a gauge reading) is not an absolute measure of the depth of the water in the channel, rather, it is a depth with respect to an historical … level,” the NWS said. “In summary, when a river gauge reads zero or in the negative numbers, it does not mean that the river has gone totally dry or is running below ground. It means that the gauge is reading at or below the agreed-upon zero level.”

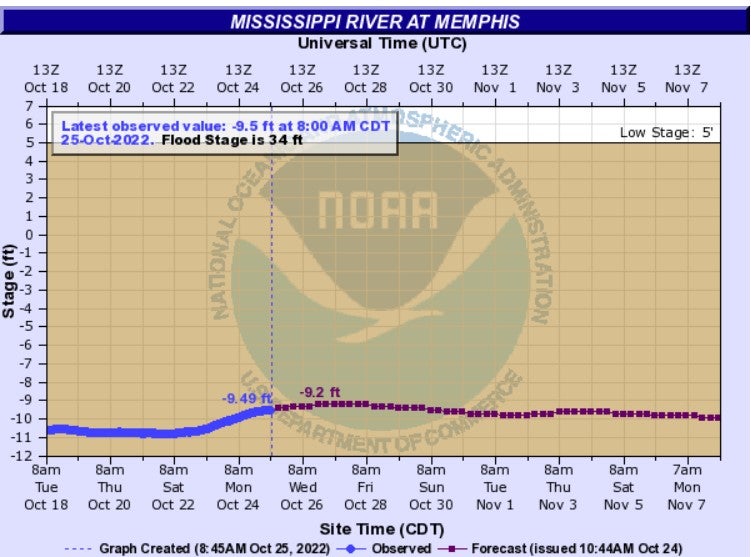

The most recent reading at Memphis is minus-9.49 feet at a location where “low stage” begins at positive 5 feet. That negative reading is actually an improvement of one that was beyond negative-10 just a week ago. Media reports described that as a record low.

But forecasts of the river’s levels in the next 10 days show it continuing to rise and then sinking back.

The low levels have led to shipping restrictions beyond the backups, which, in turn, are caused by the inability to move as many barges in one shipment as in the past.

In its statement, the Coast Guard said that limitations on the southern Mississippi mean a barge can not have a draft greater than 9 feet, and the tows can be no more than five barges wide.

Steenhoek said that in normal conditions, an additional one or two barges across might be shipped, and drafts can be as much as 12 to 14 feet.

Steenhoek’s organization of soybean and soy product shippers is a key user of the Mississippi River, primarily to move soy to the Port of New Orleans where it is transferred to bulk carriers for export to all parts of the world.

Given that, the low levels of the Mississippi are particularly problematic in October for his group’s members, Steenhoek said.

“We are more and more into the heart of harvest season, when there’s all this production coming on line,” Steenhoek said. “[The harvest this year was] significant, and the transportation system is not in position to be able to accommodate it like it does normally. So you have an incompatibility between the supply chain and supply.”

With barges backing up and a limited ability to move them, barge rates are collapsing, according to the Department of Agriculture. In its Grain Transportation Report for Oct. 20, the agriculture department said the St. Louis barge spot rate fell to $72.58 per ton from a peak of $105.85 just two weeks ago.

“Amid uncertainty about when barge traffic will normalize, some grain shippers have delayed deliveries until later in the year, which has softened demand for barges,” the report said.

But even with that decline, the report said the spot rate is up 130% from a year ago and has risen 260% from the three-year average.

Its forecast on when things might improve for water depths said the current situation may last “at least through October based on forecast precipitation.” But the end of October is just six days away, and precipitation forecasts are not abnormally high.

Steenhoek said some farmers may be able to stay out of the market and its transit problems because of on-site storage.

“One of the big developments in the last 15 to 20 years has been an increase and proliferation of on-farm storage,” he said. “It does really pay farmers to invest some money in storage so they can market what they grow throughout the year and take advantage of price increases when they occur.”

Steenhoek added that the normal course of activity in the soybean market is that the North American harvest occurs during the Latin American winter, when it is not in position to sell a steady supply of beans into the market. That shifts as the Northern Hemisphere goes into winter and summer takes over in the south.

At a recent visit to a barge-loading facility, Steenhoek said he saw farmers lined up for a five- to seven-hour wait when the time usually is minimal. With fewer barges and a smaller number of barge groupings on the water, “that tells me there are not a lot of alternatives,” he said.

There are other alternatives, but they aren’t desirable. Railing beans and soy products to the West Coast for transport from there is possible, “but now when the rail system is under stress and it is not operating with the kind of reliability,” he said, the ability of many shippers to take advantage of that option is limited.

“You can’t just have this wholesale shift from mode A to mode B,” Steenhoek said.

Several weather observers have noted that with the ground in the Mississippi River basin so dry, any upcoming rains are likely to be heavily absorbed by the soil rather than becoming runoff that makes it into the streams and rivers that feed the main waterway. That pushes off the day when transit may return to normal.

More articles by John Kingston

XPO brokerage spinoff RXO gets near-investment-grade debt rating from S&P

DOE methodology for determining diesel prices sees 2 key changes