U.S. imports showed signs of life in March, rebounding from February, but the outlook remains highly uncertain. New data shows that wholesale inventories remain very high, while cargo flows from China are sinking.

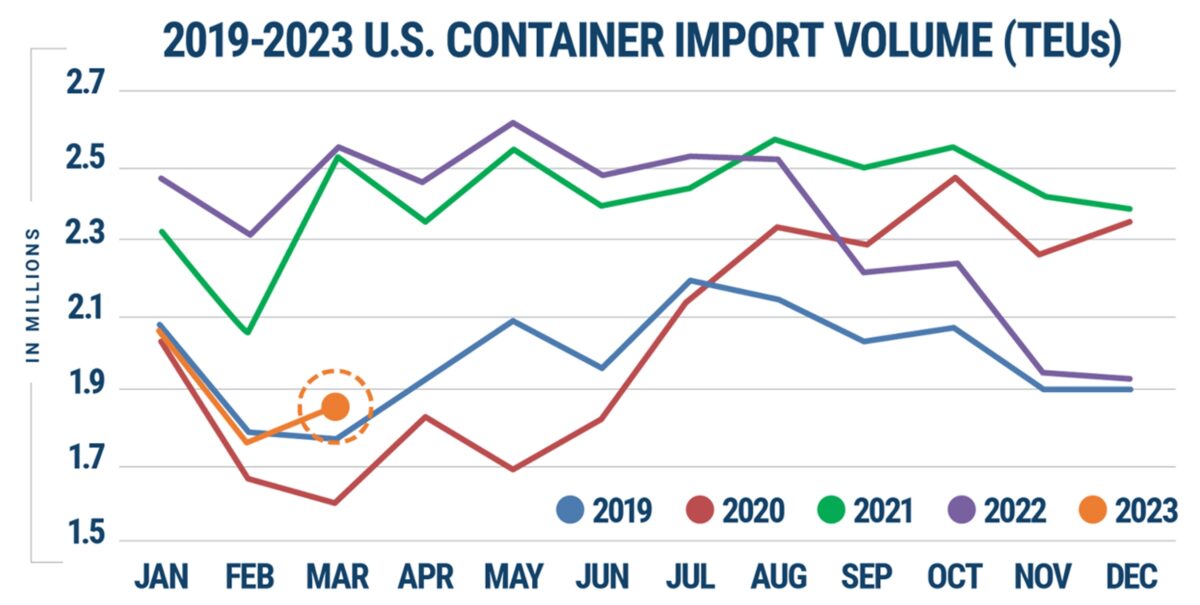

According to data released by Descartes on Tuesday, U.S. imports totaled 1,853,705 twenty-foot equivalent units in March, down 27.5% year on year but up 6.9% from February and up 4.2% from March 2019, pre-COVID.

The big winners were Los Angeles and Long Beach, where imports rose 30% and 25% versus February, respectively, according to Descartes. The Southern California ports had been particularly hard hit by Lunar New Year disruptions in February.

Descartes’ data showed month-on-month drops along the East Coast, with Savannah down 6%, New York and New Jersey 5% and Charleston 3%.

Continued declines from China

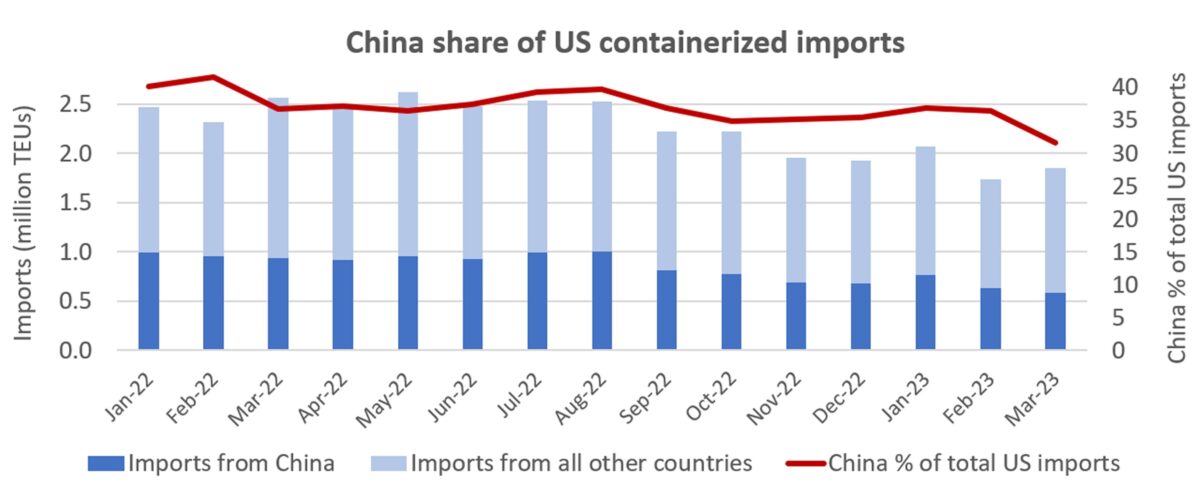

The bounce back in Southern California came despite falling import flows to the U.S. from China. Imports from China declined by 46,573 TEUs in March versus February, according to Descartes, counterbalanced by a similar combined increase from Thailand, South Korea and Japan.

U.S. imports from China totaled 586,129 TEUs in March, a 41.6% plunge from the recent high in August 2022. (U.S. imports overall fell 26.7% during the same period.)

According to Descartes, imports from China accounted for 41.5% of the U.S. total in February 2022. By last month, China’s share had fallen all the way down to 31.6%.

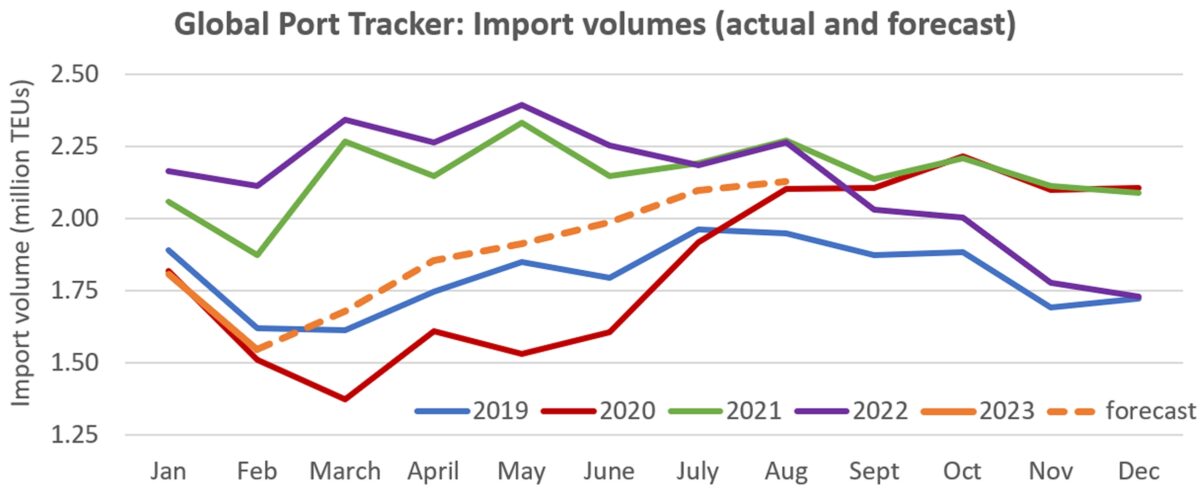

The National Retail Federation (NRF) expects U.S. imports to continue to climb in the months ahead, but not to the levels seen during the pandemic.

The Global Port Tracker report, published by the NRF and Hackett Associates, covers import flows to 12 U.S. ports. It estimates that imports to those facilities will total 1.68 million TEUs in March, up 8.3% versus February.

Global Port Tracker currently forecasts imports will continue to rise month on month, climbing to 2.13 million TEUs by August, up 26.7% from estimated March levels.

“The numbers we’re expecting would have been considered normal before the pandemic,” said Jonathan Gold, the NRF’s vice president for supply chain and customs policy. “The priority at the moment is resolving labor negotiations at West Coast ports and avoiding any self-inflicted supply chain challenges on top of those we’ve faced the past three years.”

Wholesale inventories still very high

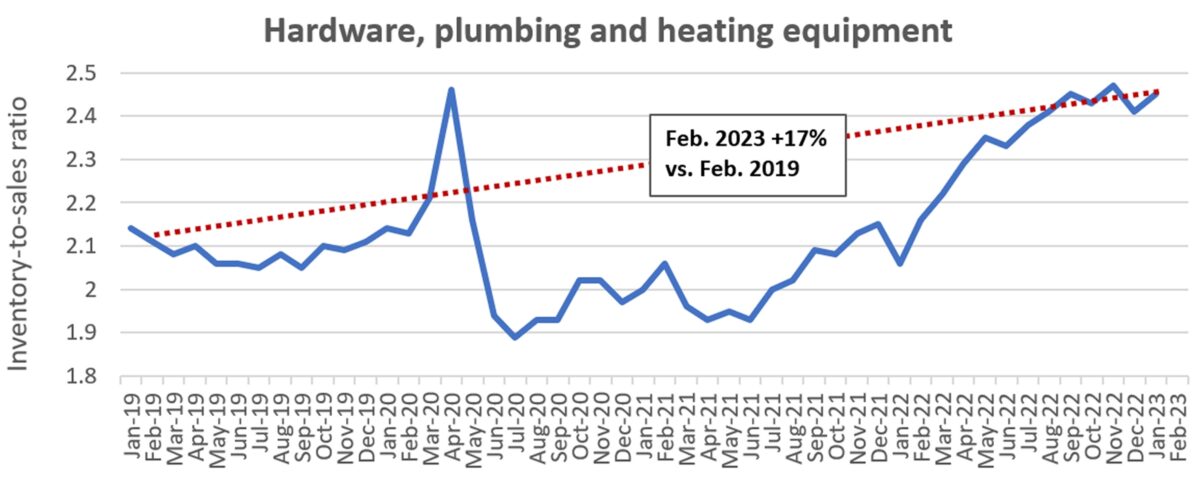

The risk to the modest rebound predicted by the NRF is that bloated inventories take longer than expected to unwind.

Census Bureau data on February wholesale inventory-to-sales ratios was released Monday (as well as revisions to early months’ data). Three categories of containerized goods show very large inventory overhangs, with very limited progress to date on reducing the excess.

Wholesale inventory of hardware, plumbing and heating equipment was 2.47 times sales as of February, up 17% from February 2019, pre-COVID. The February ratio was at a post-pandemic high, matching the previous high in November.

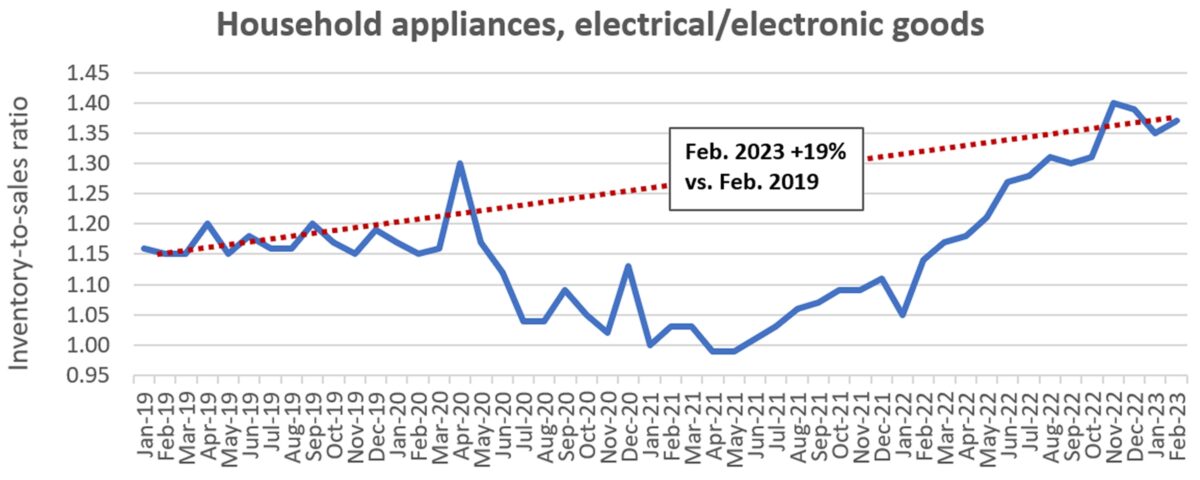

The wholesale inventory-to-sales ratio for household appliances and electrical and electronic goods was at 1.37 in February, not far below the peak of 1.4 hit in November. The ratio was still 19% above the February 2019 level.

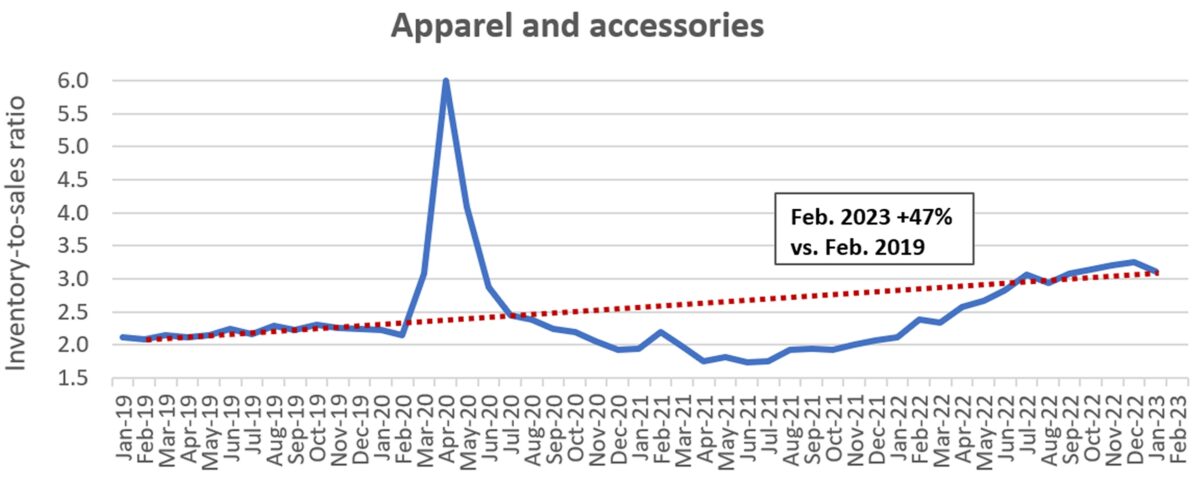

The situation for wholesale apparel and accessories is by far the worst. Inventory was 3.04 times sales in February, versus the post-pandemic peak of 3.26 in December. This February’s ratio was 46% higher than February 2019’s.

Is the supply chain back to normal?

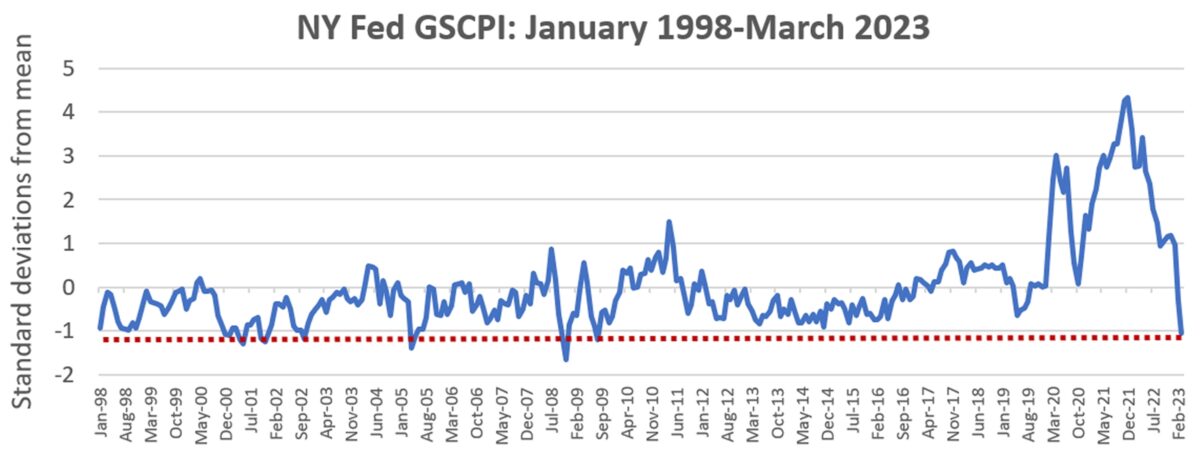

Port congestion has cleared as imports have declined from the peak. Ship queues off U.S. ports are now virtually non-existent. The Global Supply Chain Pressure Index (GSCPI), published by the New York Federal Reserve, implies that the supply chain conditions have now normalized. The index reading for March plunged to 1.06 standard deviations below the historical mean.

However, the GSCPI methodology has been the target of criticism. Other indicators point to a significant improvement since the COVID-era crunch, but not a return to full normalcy.

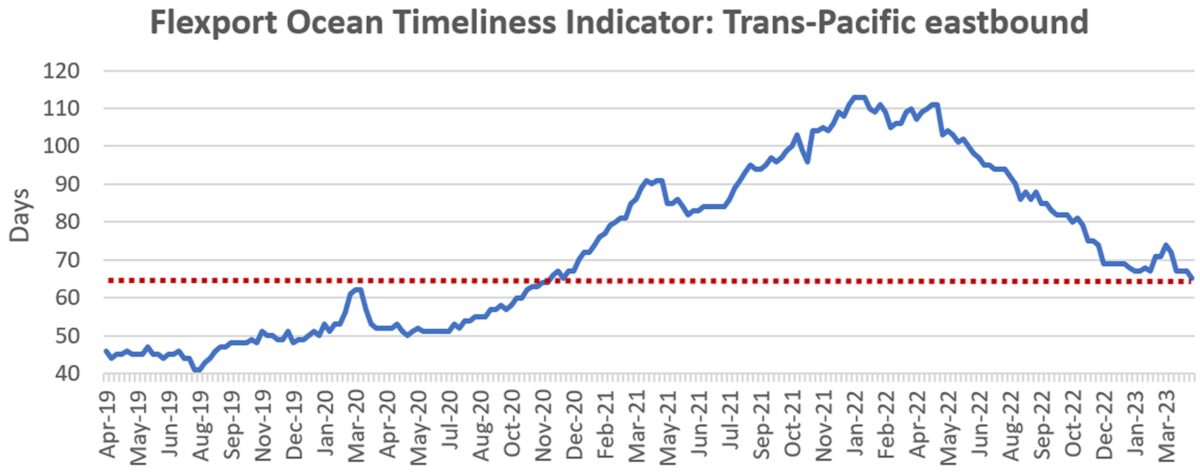

Flexport publishes a weekly measure called the Ocean Timeliness Indicator (OTI). The OTI tracks the number of days from the time containers leave factories in Asia to when they exit terminal gates at U.S. ports.

The trans-Pacific eastbound OTI for the week ending Sunday was 65 days. That’s down 42% from the peak of 113 days in January 2022. But it’s still 40% above the 2019 average of 46.4 days. (The OTI may also have increased versus 2019 because more cargo is taking the longer route to East and Gulf Coast ports.)

Data on cargo “rolls” also shows major improvements but not a full normalization. Project44 data on FreightWaves SONAR tracks the global weekly percentage of cargo arriving on a different ship than it was originally booked.

As of the first week of April, this indicator was down 48% from its January 2022 high but was still 26% above the average in the second half of 2019.

Click for more articles by Greg Miller

Related articles:

- Container lines still up vs. pre-COVID despite fall from peak

- Mixed signals: Container shipping downturn not following the script

- Mighty fall: Container line profits plummet from historic peak

- LA-LB outlook darkens as labor unrest briefly shutters ports

- West Coast wipeout: Los Angeles, Long Beach imports still sinking

- Imports sink again as wholesale inventories remain bloated

- The Fed’s supply chain pressure gauge just went negative