Elmer Bontrager, a Kentucky-based truck driver, doesn’t mind his overly helpful big rig. But he knows it has its limits.

Bontrager’s semi-truck wants to alert him whenever it seems like he’s going to mess up. The problem is, the truck isn’t always correct. A weigh station, for example, might have a stop sign where the truck only needs to stop if another light is red; his know-it-all truck might want to stop anyways. Or, his truck may confuse tire tracks or cracks in the pavement with lane markings, or believe a trash can on the side of a curvy rural street is a car he’s about to smash into. The techy truck, provided to him by his employer, can’t distinguish between a threat and a routine blip.

“[T]he technology doesn’t always work as intended,” Bontrager, who lives in a small town in southwest Kentucky, wrote in an email to FreightWaves. “I think technology works best in an environment where everything is rational, which is probably the case in a computer program or even in a computer simulation. Unfortunately in the real-world operational environment decisions are made and actions are taken by humans, and humans very often make irrational decisions and take irrational actions.”

So-called advanced driver-assistance systems have become ubiquitous in trucks over the past 10 years, said Suman Narayanan, director of engineering of Dailmer Trucks North America’s Automated Technology Group. These technologies monitor if a driver is abiding by lane markings, keeping appropriate distance from the vehicle ahead and other key driving activities. Narayanan said the technologies have the “potential to mitigate accidents,” but they are “not a replacement for highly attentive and well-trained driver.”

These trucks are not taking over the job of driving, but these features certainly may result in drivers who relax their attention. In turn, fleets are increasingly installing inward-facing cameras to monitor whether truck drivers are paying attention while driving. Motive, one such provider of AI-powered, driver-facing cameras, says fleets enjoyed 57% fewer accidents within four months of deploying Motive cameras and a 30% reduction in accident-related costs.

“You see a lot of fleets installing cameras,” said Annette Sandberg, a transportation safety consultant and former administrator of the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration. “A part of it is, ‘Listen, you still have to be paying attention.’ Let’s say a car spins out in a lane beside you and all of the sudden it’s in front of you. From a fleet perspective, while they expect the system to catch that, they also want to see that the driver is doing everything they can to avoid that . … They still expect the driver to be able to understand and address that appropriately.”

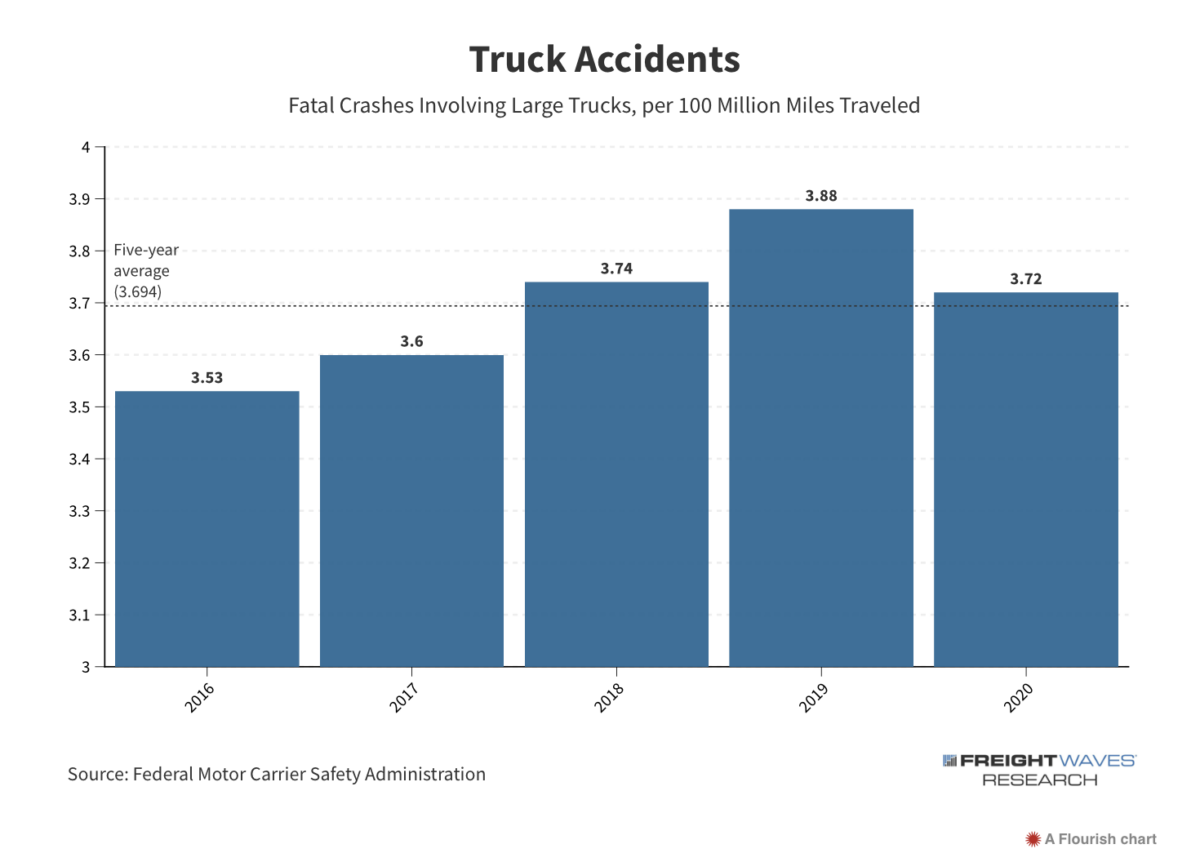

Some of that increased surveillance is required by federal regulations; since 2018, trucks are required to be outfitted with an ELD that ensures drivers are hewing to hours-of-service laws. Interestingly, since that mandate, fatal crashes involving large trucks have actually increased. Speeding violations have also increased during that time.

As trucks become more advanced, the surveillance of drivers will likely increase. That makes some drivers question why the technology is getting introduced in the first place.

“About half of our fleet is new enough to have these ‘safety’ features,” truck driver Benjamin Reed, who drives for a family-owned fleet based in Wisconsin, wrote in an email. “My experience (and that of my colleagues) has been that these systems are quirky, unreliable, and unpredictable, regardless of who manufactured them or what type of vehicle they’re installed in. I believe that the recent push to replace competence with computers is a very bad idea.”

The ‘mushy middle’ problem might be driving more truck driver surveillance

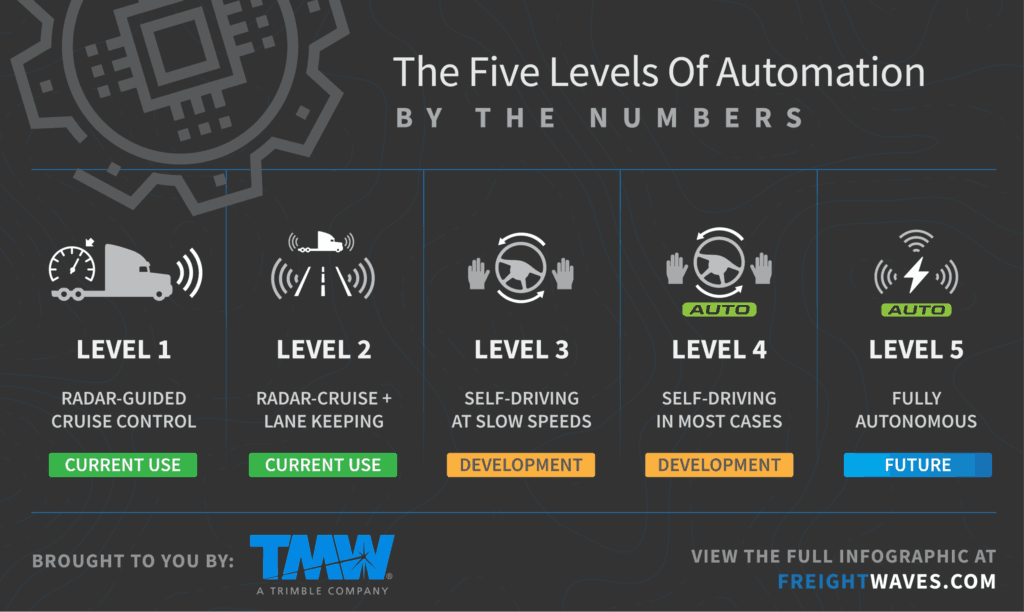

There are five levels of automation. Most passenger drivers have experience with Level 1, with features like adaptive cruise control, and perhaps Level 2, where the vehicle monitors lane keeping.

In both commercial and passenger driving, Level 3 is unlikely to be broadly adopted. It’s costlier than the less advanced systems but still requires fleets to keep a driver in the truck.

What’s more, it greatly contributes to an issue called “passive fatigue.” Many studies have shown that when drivers don’t really need to do anything, they’re more likely to zone out. The robot truck, in these cases, is able to handle the bulk of the truck driving job — namely barrelling down a highway at a legal speed. Humans are expected to quickly intervene, however, in the case of a potential collision.

“The more technology assists in driving the truck the less the driver has to focus on driving and because of that I think it can actually have an adverse effect on safety,” Bontrager said.

One study found that passenger drivers in an automated vehicle driving simulator were pretty, well, bad at quickly responding in the event of a crash. About a fifth didn’t do anything when their automated vehicle swerved toward a closed highway exit. Another study found that drivers began showing facial signs of fatigue during an automated driving simulation after about 15 to 35 minutes of driving, and responded more slowly to a takeover request than drivers using a traditional system. Several other studies have indicated that driver attention fades while behind the wheel of a semi-autonomous vehicle.

It’s not clear if this has a direct correspondence to the trucking world, where drivers are decidedly not in a simulator. Narayanan said proper training of truck drivers for using these new systems is key.

Some technology providers don’t want to deal with the ‘mushy middle’

The issue of passive fatigue is why some startups in the driverless trucking space are ignoring the lower levels of autonomous driving. They’re seeking to jump right into a fully driverless solution. Representatives of Gatik, Aurora and Kodiak Robotics all told FreightWaves they’re only developing driverless technology — though well-trained safety drivers are still behind the wheel of these trucks.

“You need to take a lot of steps to ensure that the driver continues to stay engaged,” said Don Burnette, founder and CEO of Kodiak. “We would prefer to avoid all of that complexity altogether.”

Richard Steiner, vice president of government relations at Gatik, said regulators have shared their own concerns about the lower levels of automation.

“When you have vehicles which involve partial automation, are the drivers trained to understand what that partial automation really entails and really means?” Steiner said. “Do they know that they are ultimately entirely responsible and should act as the driver? Do they understand human factors, and how that interplay really plays out? Do they understand automation’s place in all these things?”

These startups intend to have truly driverless trucks regularly running freight in the coming years. As of today, neither company is running particularly long hauls. Kodiak trucks currently operate from Dallas to Houston, Oklahoma City and Atlanta. Gatik trucks operate up to 300 miles round-trip.

That ma be concerning news for America’s 2.2 million truck drivers. But for now, many appear more concerned about the encroaching surveillance into their workplace — the truck where they eat, sleep, work and so on. Some have reported success in rebuffing driver-facing cameras.

“We do have dashboard cameras in our fleet, but no driver-facing cameras,” said Reed, the Wisconsin-based truck driver. “That particular subject has come up only once at my current company and the owner met with fierce resistance at the mere mention of them. The general opinion was that the day they make an appearance at our company is the day we leave en masse-expressed in language hardly suitable for print and at a volume appropriate only for a Space Shuttle launch.”

What do you think? Email rpremack@freightwaves.com. Don’t forget to subscribe to MODES.