Will the Baltic Exchange’s changes to the BDI make it tradable?

In 2016, the global market for container shipping was in the depths of a multi-year slump caused by a persistent mismatch in supply and demand. A spate of new ships in prior years had created a glut in capacity, weak Chinese GDP growth weakened demand at the same time, and a fresh round of ship orders threatened to keep prices at rock-bottom for even longer.

The Baltic Exchange, that venerable London institution dating back to 1744 providing freight market information to maritime shipping interests and publishing a number of non-tradable indices, was struggling. After a number of attempts by the London Metals Exchange and other suitors to acquire the Baltic, Baltic’s shareholders agreed to be purchased by the Singapore Exchange in September 2016.

“In terms of a deal, the possibility arose when it became clear that the Baltic was worth substantially more than the shares were trading for and that there was interest out there in an acquisition,” outgoing Baltic Exchange Chief Executive Jeremy Penn told Reuters.

The Singapore Exchange (SGX) was founded in 1999 and in recent years has embarked on a quest to be recognized as the center of global trade and shipping finance. Since 2010, SGX has attempted a number of aggressive acquisitions and mergers: in 2010-1, SGX tried but failed to merge with the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX); and in 2012 SGX was reportedly in merger talks with the London Stock Exchange, but that didn’t go anywhere.

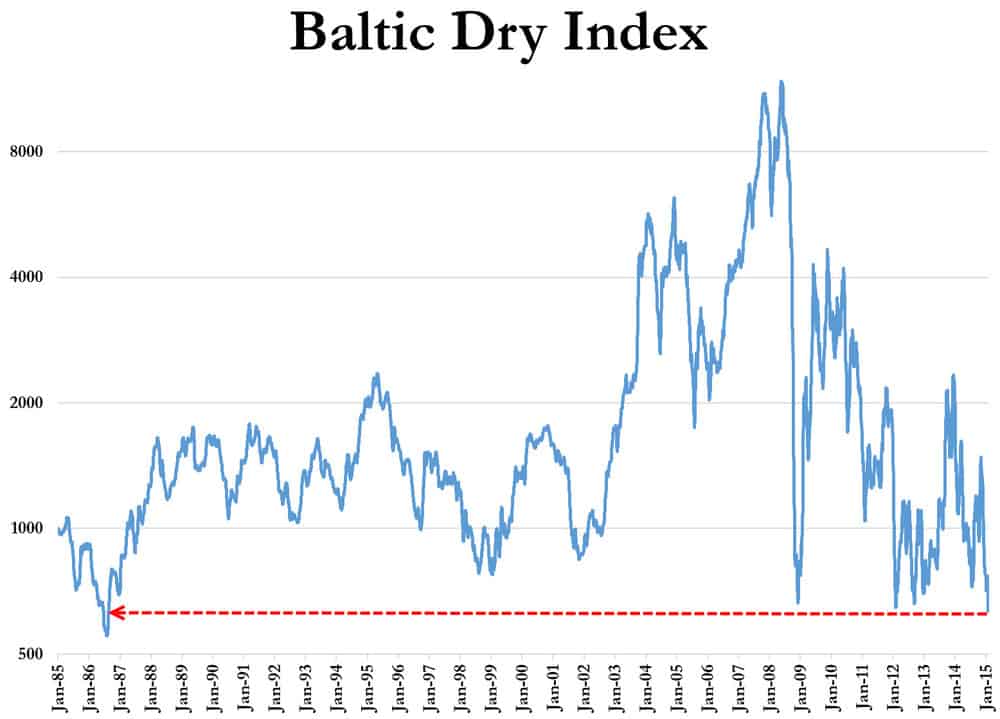

The Baltic Exchange’s new owners want to rev up investment activity by transforming one of Baltic’s premier indexes, the Baltic Dry Index (BDI). This index averages out the price of moving non-containerized raw materials like coal, ores, grains, and cement on 23 different global shipping lanes.

The BDI itself is not really traded against on the futures market other than a few over the counter notes because it does not represent a single commodity—it combines separate indices for Capesize (100K+ deadweight tons), Panamax (60-80K DWT), Supramax (45-59K DWT), and Handysize (15-35K DWT) ships. The indices representing the three largest classes of ship, Capesize, Panamax, and Supramax, are quite volatile because supply is inelastic. In other words, it’s extremely expensive and time-consuming to remove or add supply to the marketplace—it takes years to design, order, build, and deliver a large ship, and it costs too much money to take one of these massive freighters out of water into storage if there’s a temporary drop in demand. Therefore, dry bulk carriers are not able to respond to changes in demand, which can occur rapidly. Since the carriers cannot effectively take ships offline or bring them back online to respond to fast-moving market conditions, the shipping rate itself fluctuates wildly, with even marginal changes in demand having outsize effects on rates.

That is not the case for the smaller Handysize ships, though. They are cheaper and faster to build, easier to lay up when they aren’t needed, and they generally serve regional markets. Because the supply of Handysize capacity is elastic, then, there’s very little volatility in rates—carriers are better at matching supply to demand. The volatility of Capesize, Panamax, and Supramax rates have made them attractive for derivatives investors. If you’re a bulk carrier and you’re worried that rates may go down, you can hedge that risk by taking a short position against the rate. That way, if the rate goes up, you’re getting paid more to move freight, but if it goes down, your bet on the futures market pays off. That hasn’t been the case with the Handysize ships: because the rates do not move up or down very much, there isn’t as much need to hedge against price risk with a futures contract.

The old version of the BDI—the one that the Baltic Exchange will continue to publish until March 1—weighted all four classes of ships equally, each size representing 25%. This meant that there was a lot of ‘dead weight’ in the index, so to speak: it would not actually move with the rates investors were most worried about, those of three largest classes. The 25% weight given to the relatively stable Handysize rates made the BDI less responsive, therefore less informative, and therefore less useful. The other aspect of the BDI that made it an imperfect basis for a derivatives market is its composite nature. In a trucking analogy, the BDI is like an average of dry van, reefer, and flat bed rates—it might tell you something about the general nature of supply, demand, and economic activity in a given market, but if you’re exclusively a refrigerated carrier, the reefer rate is the only one you care about.

The new version of the BDI eliminates the Handysize component and weights Capesize rates at 40%, Panamax rates at 30%, and Supramax rates at 30%. The Baltic Exchange said they made the decision to adjust the composition of the index based on commodities and financial markets that had shown interest in trading the BDI.

“We’re excited by the prospect of exchange traded funds based on the BDI and are confident that the BDI will remain an accurate general measure of the health of the dry bulk shipping markets,” said Stefan Albertijn, Baltic Index Council Chair.

Baltic Exchange Chief Executive Mark Jackson said, “The Baltic Exchange has been publishing the Baltic Dry Index (BDI) in various forms since 1985 when it started life as the Baltic Freight Index (BFI). Like any aggregate index, its composition has changed over the years to reflect changes to the underlying market. In our case this means ensuring that the BDI broadly reflects dry bulk global trading patterns. The new weightings are simply the next phase of development in this process.”

Stay up-to-date with the latest commentary and insights on FreightTech and the impact to the markets by subscribing.