Last mile delivery has always been a tough nut to crack, but the exponential growth of e-commerce has made the problem even more urgent. Forward-thinking companies in the space have developed a number of strategies to deal with the well-known last-mile delivery pain points. Last-mile delivery is low-revenue, labor-intensive, is characterized by unpredictable network density and a lack of revenue-generating backhauls, and can be very seasonally volatile: all factors that make last-mile the place where transportation profits go to die.

The only parcel service that provides truly universal last mile delivery coverage in the United States is the US Postal Service, which runs a $6B annual deficit, but it’s a public service funded by tax dollars and not a for-profit corporation.

UPS has a mind-bogglingly-large pool of vehicles and drivers to bring packages all over the world, but has increasingly relied on ‘Postal Injection’ to limit their exposure to last-mile inefficiencies and costs. With Postal Injection, UPS delivers a pallet to a local post office containing packages to be delivered in the same zip code; the post office breaks down the pallet, puts it in various trucks, and performs last mile. With Postal Injection, UPS handles intake, consolidation, and line haul, and avoids last mile pain points.

XPO Logistics has tackled last mile delivery in a different way, by focusing on large, expensive consumer goods that are difficult to handle—think of couches, refrigerators, ovens, and other bulky, awkward appliances. The key for this freight is that it’s high value goods at a higher margin and consumers are willing to pay high delivery fees.

Amazon, on the other hand, seems to have taken a page from FedEx Ground’s playbook—a network of owner-operator ‘independent contractors’ who lease-to-own their vehicles. Amazon Logistics first bought 5,000 Mercedes-Benz Sprinter vans for their new ‘Delivery Service Partner’ program, which it describes as a way to help people launch small delivery businesses. Yesterday, Amazon announced an additional order for 20,000 Sprinter vans, signaling that just like in every other part of its business, Amazon will pursue rapid scale.

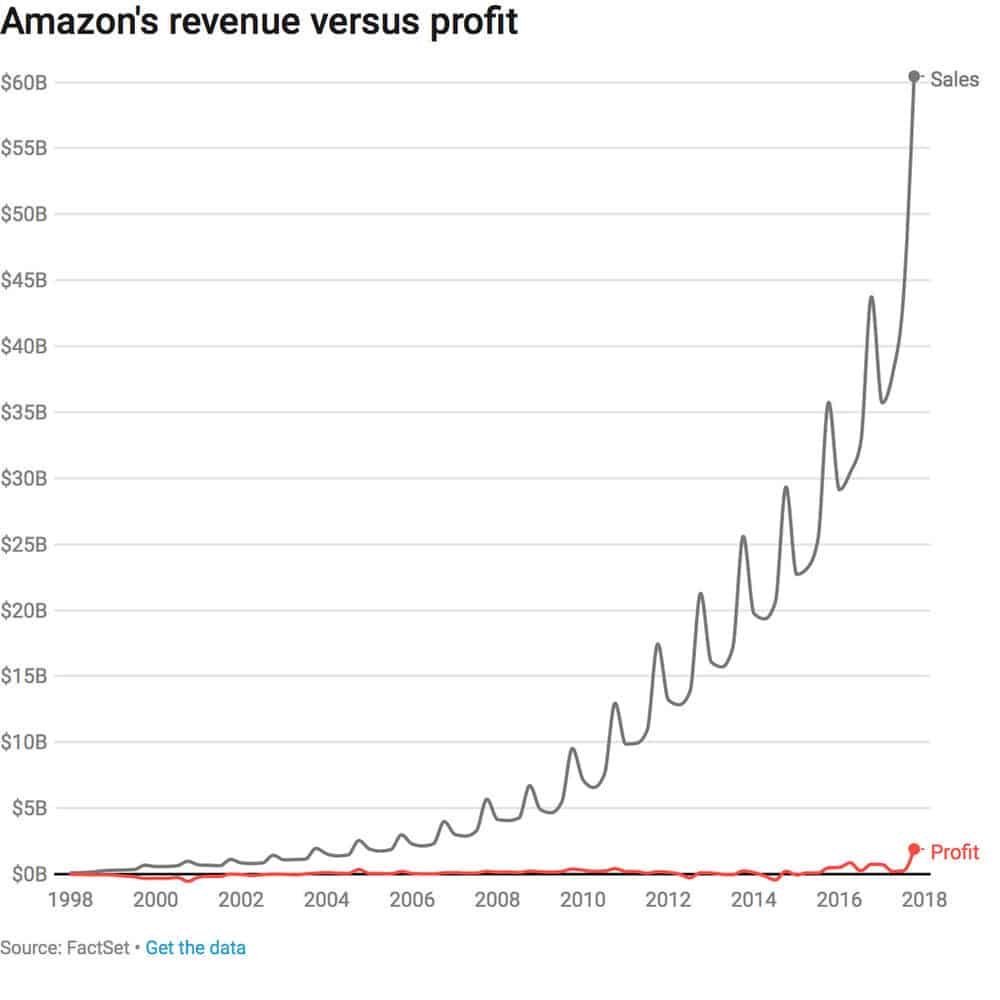

Drivers interested in delivering for Amazon are expected to wear Amazon-branded uniforms and drive Sprinters with Amazon Prime logos. Drivers can lease a total of 40 vans from Amazon, and the company claims that its delivery service partners could gross $300K per year. However, look at the chart below:

The most obvious movement in the chart comes from Amazon’s hockey stick growth up and to the right. But there’s a problem for delivery service partners in the seasonal volatility that is growing more and more exaggerated as Amazon scales, not less. Delivery service partners with van lease payments might be left holding the bag in periods of relatively low volume, and forced to scramble in our increasingly frenetic e-commerce-powered holiday seasons. The Whole Foods grocery business, though, is less seasonal than e-commerce, and should help smooth out some of that volatility.

Still we think thatAmazon’s independent-contractor lease-to-own model for last mile delivery meshes well with its overall strategy of driving down cost and owning a larger and larger piece of the customer experience.

While Amazon is just getting into last-mile delivery, its linehaul business is already well-established and is now poised to start throwing its weight around. Amazon already has 9,000 trailers and we’ve heard from owner-operators that Amazon is getting rid of enterprise carriers and relying more on their own carrier pool, bringing in drivers through the Amazon Relay app, launched under the radar in the fourth quarter of 2017. Amazon’s on track to have 40,000 trailers in three years. FreightWaves has also learned that Amazon is in the middle of reconfiguring its routing guides, cutting some enterprise carriers completely out and shifting others to power only.