The Boeing Co. (NYSE: BA) on Monday said it was replacing CEO Dennis Muilenburg with Chairman David L. Calhoun as the aerospace manufacturer continues to lose money and public trust over its handling of the 737 MAX crisis following two crashes that killed 346 within the past year.

Chief Financial Officer Greg Smith will serve as interim CEO during a brief transition period, while Calhoun exits his non-Boeing commitments, Boeing said Dec. 23.

Board member Lawrence W. Kellner was named chairman of the board. Calhoun will remain a member of the board. The changes are effective immediately.

“The board of directors decided that a change in leadership was necessary to restore confidence in the company moving forward as it works to repair relationships with regulators, customers and all other stakeholders,” Boeing announced. “Under the company’s new leadership, Boeing will operate with a renewed commitment to full transparency, including effective and proactive communication with the Federal Aviation Administration, other global regulators and its customers.”

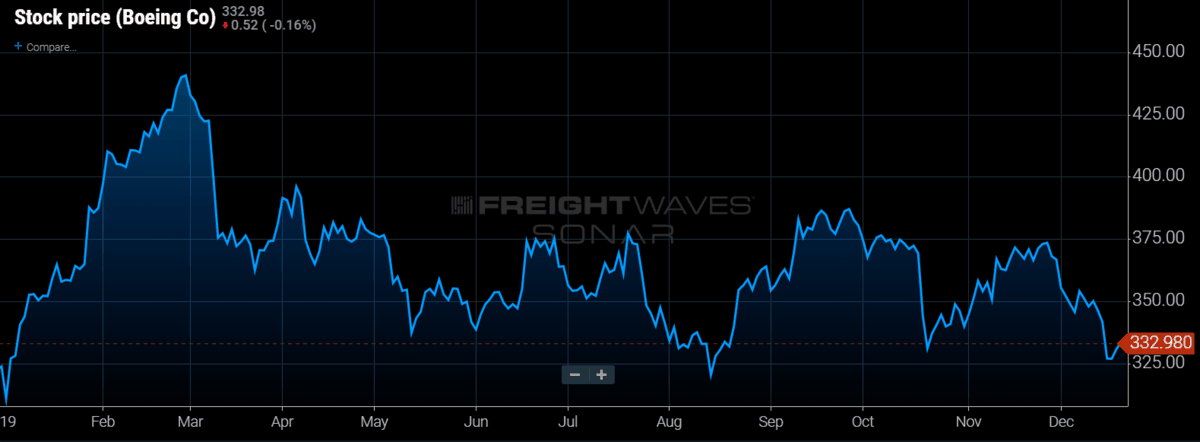

Boeing’s stock price has dropped 25% since the second crash of an Ethiopian Airlines plane. Boeing, headquartered in Chicago, is also under heavy congressional scrutiny because of the accidents and how it has responded to them.

Returning the new, more efficient 737 model, which has received more orders than any other Boeing plane, to service has taken longer than the company anticipated. The delay is hurting its bottom line and reputation. Boeing officials led airline customers to believe that the plane would be certified to fly again within months of its March grounding by regulators after it made software fixes to address problems with the automated flight control system implicated in the crashes. Boeing is also updating pilot training procedures associated with the complex system.

Most recently, Boeing indicated that the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) would clear the plane for service by late November or December and airlines adjusted their schedules for resuming MAX service in January. But two weeks ago FAA Administrator Stephen Dickson indicated the agency’s review probably wouldn’t be completed until sometime in the first quarter of 2020, leading Boeing to announce it will halt production of the 737 MAX in January until the situation is resolved.

Boeing had slowed production to 42 planes per month and has nearly 400 on the ground awaiting delivery.

Other dominoes quickly fell. Major supplier Spirit AeroSystems said it would shut down its assembly line that builds fuselages for the 737 MAX, putting workers in limbo and jeopardizing its finances. American Airlines and Southwest Airlines pushed back their schedules for the MAX’s return to service until early April, followed by United Airlines’ decision to cancel 737 MAX flights until June 4.

In mid-October, the board stripped Muilenburg of his dual role as chairman and gave the role to Calhoun, a director at the time.

The delayed certification for the 737 MAX is hurting Boeing’s order book, cash flow and future earnings. The commercial airplane unit experienced a 41% fall in revenues in the third quarter, reflecting lower 737 deliveries.

Boeing was scheduled to produce more than 1,200 MAX aircraft in 2019 and 2020, according to at least one estimate.

The airframer has already set aside $5 billion to compensate airlines for the planes’ loss of use and is also paying families of victims in the two crashes.

Boeing’s troubles have been compounded by allegations that the company held back critical information about potential problems with the MAX from regulators and was prioritizing production speed over safety.

In October, government officials revealed that a former Boeing test pilot kept quiet in 2016 about problems he encountered with the MAX’s flight control system. At a House hearing in December, a Boeing whistleblower said Boeing officials didn’t address concerns about sloppy work and defects that increased as employees were stretched to work long overtime. The House hearing also revealed an FAA analysis conducted last December predicted 15 more fatal crashes over the lifetime of the 4,800 aircraft expected to be produced.