Much of the U.S. waterway system’s enormous potential for commercial transport is going to waste for lack of use or funding, according to marine and trade experts.

While most people are familiar with the importance of roads in transporting freight across the U.S., many have no idea that the more than 25,000 miles of navigable waterways — including rivers, canals and coastal routes — are just as vital.

“We have one of the world’s greatest waterway networks, but we are barely using it,” Joseph Linck, a Brownsville, Texas-based international trade and energy consultant, told FreightWaves.

Linck is founder and CEO of Globalstone LC and was the director of the Port of Brownsville in Texas from 1988-90. He’s currently working with a large investment bank that wants to start putting ocean shipping containers in hopper barges using inland waterways to offer the first long-haul container-on-barge service in the U.S.

The Intracoastal Waterway (ICW) is a 3,000-mile inland waterway running from Boston south along the Atlantic seaboard and around the southern tip of Florida, then following the Gulf of Mexico to Brownsville.

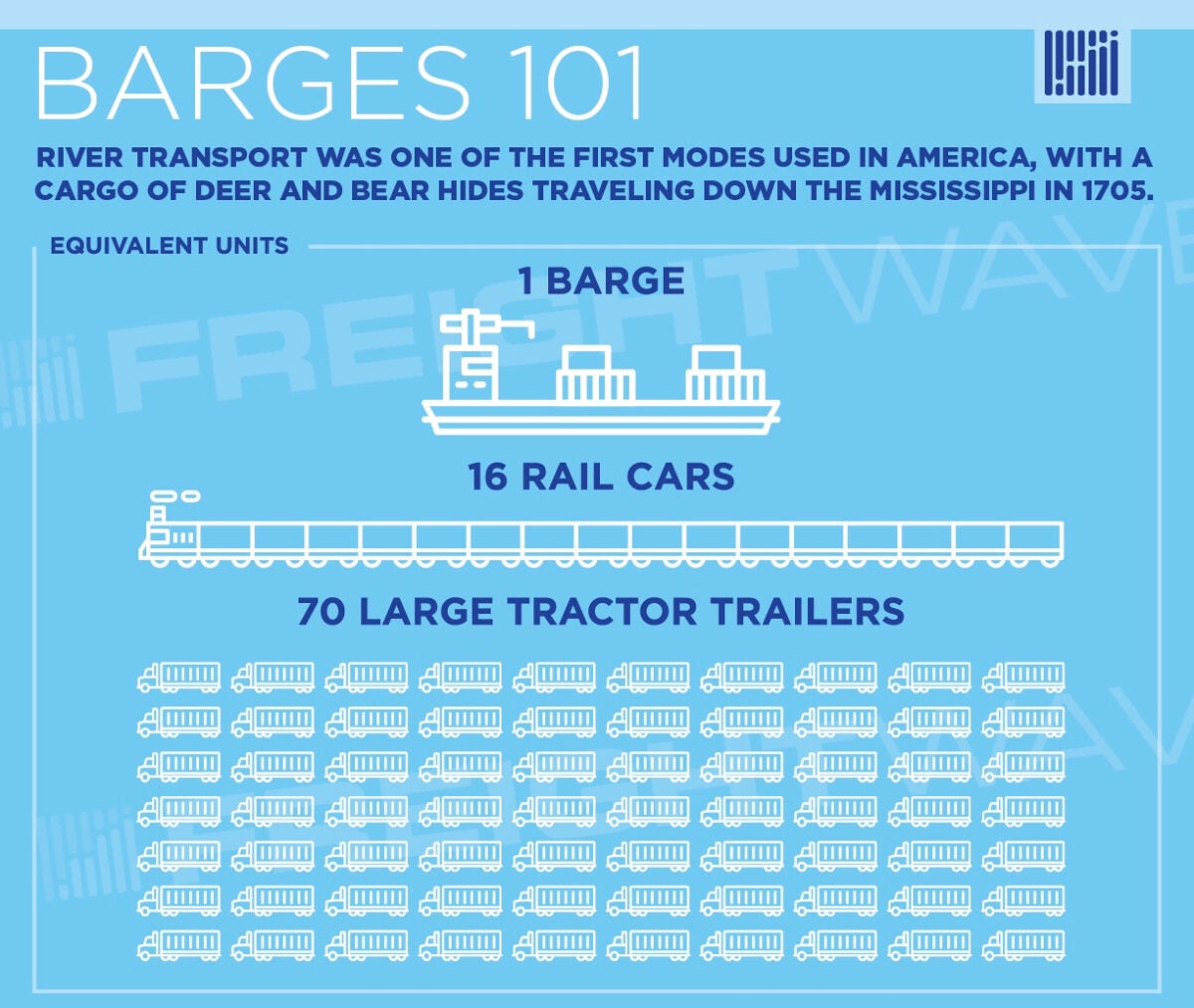

“Using the waterway, it’s a solution to the U.S. truck driver shortage, because one barge takes away 70-something trucks off the road and can move freight for less than half the price,” Linck said.

The U.S. waterway system consists of over 12,000 miles of inland waterways and 13,000 miles of coastal channels, 360 commercial ports, and 237 lock and dam chambers.

The carrying capacity of barges far outpaces tractor trailers and railcars.

The typical 15-barge tow is capable of hauling cargo totaling 22,500 tons, 767,500 bushels or 6.8 million gallons. That compares to six locomotives and 216 railcars, or 1,050 large tractor trailers.

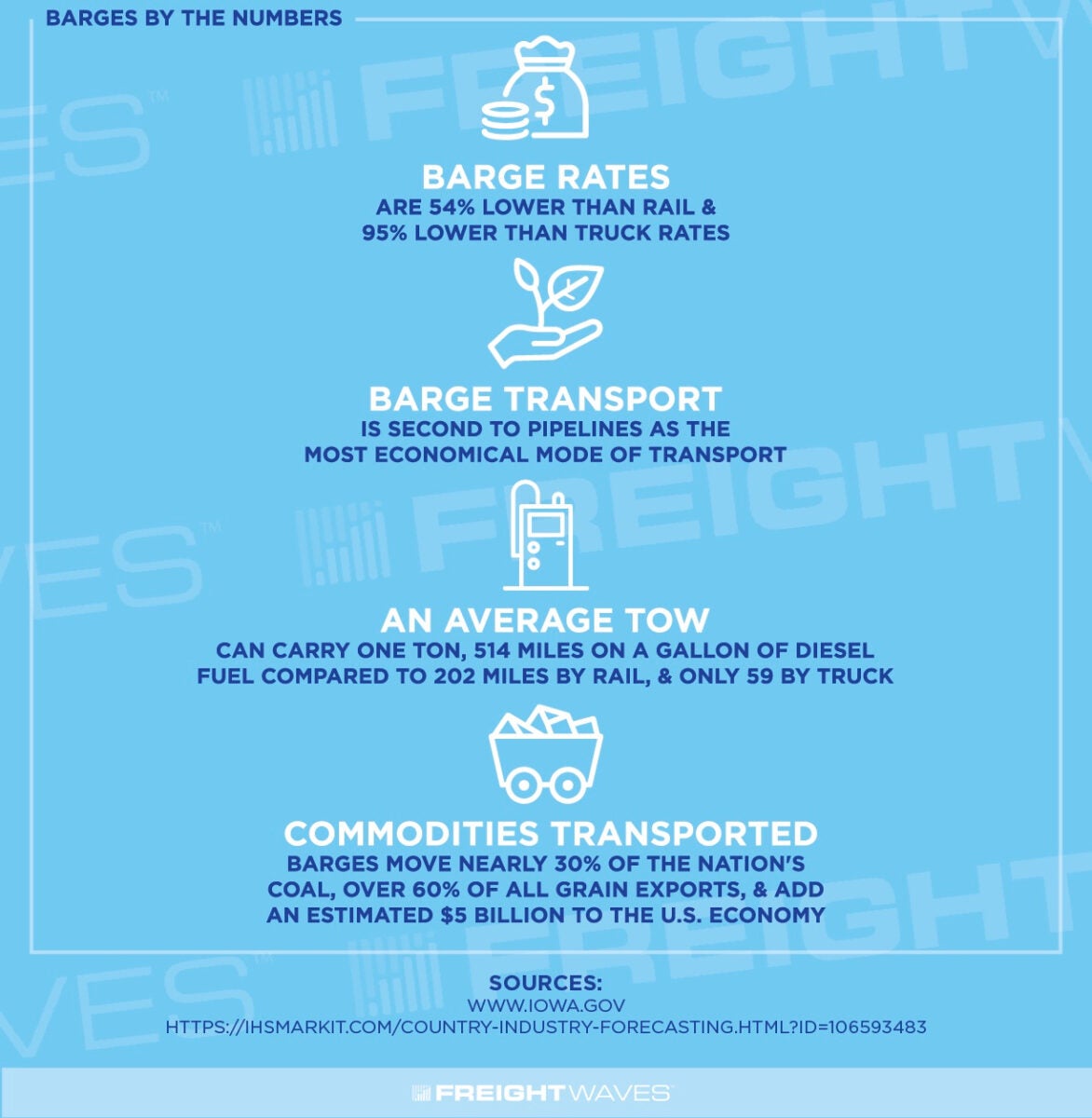

Barges can move a ton of cargo 647 miles on a single gallon of fuel, and 514 miles on diesel fuel. That compares to 477 miles by rail and 145 miles by truck, according to a 2017 study by the Center for Ports and Waterways at the Texas A&M Transportation Institute.

The Texas A&M study was commissioned by the National Waterways Foundation, a Washington D.C.-based nonprofit that addresses public policy issues related to the U.S.’ inland waterways system.

The waterway transportation system has long contributed to the competitiveness of American agriculture by transporting grain domestically and for export, National Grain and Feed Association (NGFA) officials said in an email to FreightWaves.

Corn and soybeans are the most handled agricultural commodities in the Gulf Coast region waterways, along with wheat, distiller’s dried grains with solubles and soybean meal.

“Nearly 70% of U.S. agriculture exports (137.7 million metric tons valued at $108.2 billion) were waterborne in 2019. These exports provide 20% of U.S. farm income,” NGFA said. “In the same year, the U.S. exported nearly 30% of its grain. Of this quantity, more than 50% was inspected through Mississippi River, about 30% was inspected through Pacific Northwest ports, and 5% through Texas Gulf ports.”

Paul Dittman, president of the Gulf Intracoastal Canal Association (GICA), said the waterway system is one of the safest and most efficient modes of transportation in the U.S.

“Every barge movement on our inland waterways within the Gulf Coast or any other inland waterway reduces significant amounts of truck traffic,” Dittman said.

GICA is a New Orleans-based nonprofit consisting of over 200 member companies primarily along the Gulf Coast. Its aim is to facilitate safe, reliable and efficient Gulf Coast waterways.

“The Intracoastal Waterway is the third-busiest inland waterway in the U.S. after the Mississippi and Ohio rivers,” Dittman said. “The differences on the Mississippi and Ohio River, you’re looking at about 70% dry bulk, 30% bulk liquid, whereas on the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway it’s just the opposite.”

Dittman said the ICW also provides the critical link between the U.S. petrochemical centers in Texas and Louisiana with the rest of the inland waterway system, as well as the entire Gulf Coast from St. Mark’s, Florida, to Brownsville, a distance of over 1,100 miles.

“For these reasons, the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway is often referred to as the silent giant,” Dittman said.

Petroleum products, chemicals, agricultural products, manufactured goods, coal and grains are the top commodities transported by U.S. waterways, according to the Army Corps of Engineers.

One of the biggest challenges for U.S. waterways is that historically, necessary upkeep such as dredging and infrastructure maintenance has been underfunded.

“Some of the limiting factors that we deal with include aging Army Corp of Engineers infrastructure, which can be problematic if they malfunction,” Dittman said.

One of the potential constraints to waterway transportation is the escalating volume of traffic at aging locks, the part of the waterway system that controls pool depths to make a channel deep enough for vessels to use.

Dittman said the Inner Harbor Navigation Canal Lock (IHNC) in New Orleans provides the only access to the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway east of New Orleans, creating a single point of failure if the lock is not available for navigation.

The IHNC was built in 1923. GICA is working closely with the federal government to begin the replacement of the IHNC, but this project will take several years to complete once initiated.

“It’s effectively 100 years old and is in need of replacement. We’re diligently working with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the local community to replace this aging piece of infrastructure with a new and larger lock,” Dittman said.

Some ongoing waterway projects that GICA provided input on include the $169 million Belle Chasse Bridge and Tunnel Replacement Project in Belle Chase, Louisiana, and two new bridges in Texas at South Padre Island and over the San Jacinto River along the Gulf Coast.

Like GICA, grain industry officials have been asking Congress for years to upgrade aging locks and dams on inland waterways.

NGFA officials and partnering waterways stakeholders said they are urging Congress to include funding for the Navigation and Ecosystem Sustainability Program (NESP) in final appropriations packages.

NESP is an Army Corps of Engineers program dedicated to navigation improvements and ecological restoration for the Upper Mississippi River – Illinois Waterway.

“Congress first authorized NESP in 2007, but the program has not received any construction funding. Meanwhile, the vast majority of locks on the Upper Mississippi River and Illinois Waterway (UMR-IWW), built in the 1930s and 1940s with 600-foot chambers, have long-surpassed their design life,” NGFA said.

NESP would expand the navigation capacity along the UMR-IWW through the construction of seven new 1,200-foot locks and dams. New and modernized NESP locks would allow a 15-barge tow to pass through in just one lockage, increasing efficiency and boosting U.S. competitiveness.

“Building new locks on the UMR-IWW would spur job creation and help ensure that the U.S. remains competitive as a world grain exporter. For example, the U.S. is no longer the world’s top soybean exporter and key competitors continue to lower their transportation costs by investing in infrastructure,” NGFA said.

“Research from the Department of Agriculture suggests that unless significant improvements are made to farm-to-port infrastructure, U.S. world market share could decline an additional 3-6 percentage points, resulting in $1.5 billion to $3 billion in lost export sales.”

One infrastructure project that has received support is construction funding for a new 1,200-foot lock and dam (Lock and Dam 25) on the Upper Mississippi River, which has been included in both House of Representative and Senate versions of the FY 2022 Energy and Water Appropriations bills.

“This funding has broad bipartisan support from lawmakers up and down the Mississippi River and NGFA is hopeful it will be included in a final agreement on FY 2022 spending,” NGFA said.

While maritime experts work to replace aging locks and bridges along the waterway, the U.S. faces a $47 billion funding gap in infrastructure waterway needs over the next 17 years for navigation-related waterside improvements, according to an assessment issued in January by the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE).

“The inland waterways funding gap is almost entirely for lock and dam infrastructure, which is largely antiquated and prone to failure,” according to the 170-page “Failure to Act: Ports and Inland Waterways — Anchoring the U.S. Economy.”

The ASCE also graded 17 categories of infrastructure in March. The grades ranged from a B for rail to a D-minus for transit to a D-plus for inland waterways.

“We risk significant economic losses, higher costs to consumers, businesses and manufacturers — and our quality of life — if we don’t act urgently,” Thomas Smith, ASCE executive director, said in a statement.

Another issue facing the U.S. waterway system is declining demand for coal, which has historically been a big commodity on waterways but has been on a long downward swing as the U.S. slowly decreases its dependence on fossil fuels.

The Energy Information Administration reports U.S. coal shipments by waterways declined 20% in 2020 from 2019.

In 2019, more than $134 billion worth of cargo transited America’s inland waterways, equating to about 515 million tons, according to Waterways Council Inc.

Linck said the Intracoastal Waterway helped the Port of Brownsville get back to profitability in the late 1980s.

“We initiated new cargo steel and also Midwestern grain by river barge,” Linck said. “We started at the Port of Pittsburgh on the Ohio River and brought those barges down, all the way down to the Mississippi and down the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway from New Orleans to Brownsville.”

Linck said it’s possible the U.S. waterway system also has an image problem with modern-day logistics professionals. While moving commodities by inland waterways can be more fuel-efficient and less costly, it takes more long-range planning.

“We need to reeducate all our traffic managers, give them a little more power, get these MBA bean-counting managers off their just-in-time inventory control. They can’t plan right, so they send everything on a truck. They just throw money out there and they get it where it needs to go, basically,” Linck said.

Click for more FreightWaves articles by Noi Mahoney.

More articles by Noi Mahoney

Mission produce boosts footprint with Texas avocado import facility

Nearly 300 layoffs announced at 2 logistics companies

Port Corpus Christi’s $139M channel expansion contract awarded