The many industries that make up the world of freight have undergone tremendous change over the past several decades. Each Friday, FreightWaves explores the archives of American Shipper’s nearly 70-year-old collection of shipping and maritime publications to showcase interesting freight stories of long ago.

The following is an excerpt from the October 1971 edition of the Florida Journal of Commerce.

Each of three ports along the South Atlantic coast will spend great sums of time and money during the next year to boast of its position as:

“Largest General Cargo Port” and/or “Container Port of the Southeast”

The two claims are closely related, for the handling of large amounts of general, break-bulk cargo is indicative of high potential in the container trade which each of the ports would like to dominate.

Contestants are Charleston, Jacksonville and Savannah.

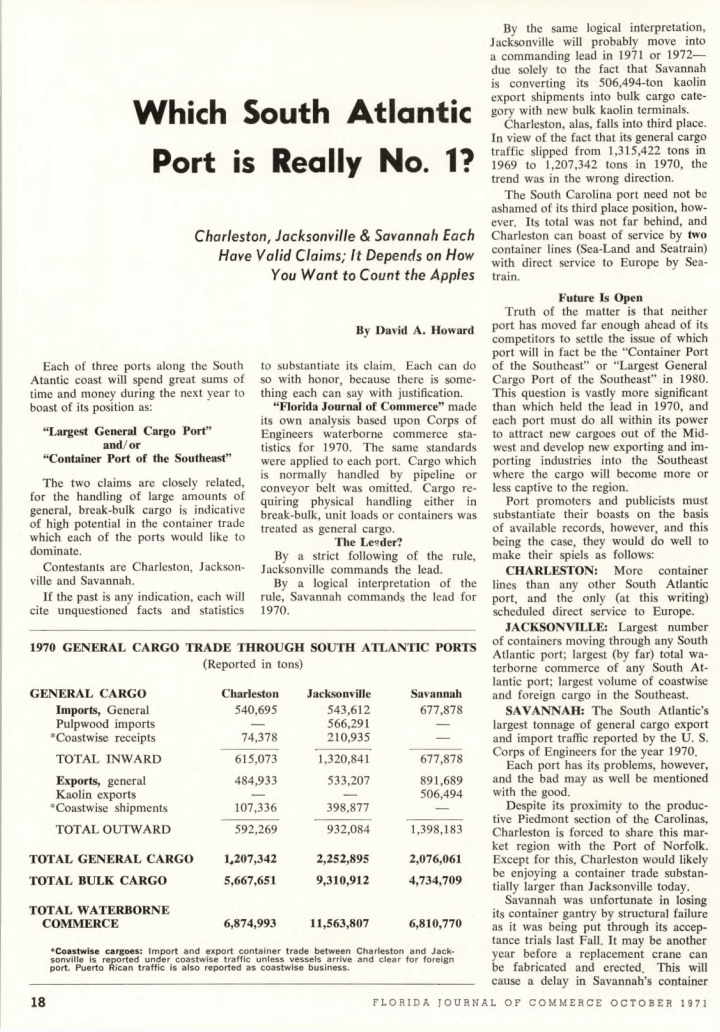

If the past is any indication, each will cite unquestioned facts and statistics to substantiate its claim. Each can do so with honor, because there is something each can say with justification. Florida Journal of Commerce made its own analysis based upon Corps of Engineers waterborne commerce statistics for 1970. The same standards were applied to each port. Cargo which is normally handled by pipeline or conveyor belt was omitted. Cargo requiring physical handling either in break-bulk, unit loads or containers was treated as general cargo.

The leader?

By a strict following of the rule, Jacksonville commands the lead.

By a logical interpretation of the rule, Savannah commands the lead for 1970.

By the same logical interpretation, Jacksonville will probably move into a commanding lead in 1971 or 1972 — due solely to the fact that Savannah is converting its 506,494-ton kaolin export shipments into bulk cargo category with new bulk kaolin terminals.

Charleston, alas, falls into third place. In view of the fact that its general cargo traffic slipped from 1,315,422 tons in 1969 to 1,207,342 tons in 1970, the trend was in the wrong direction.

The South Carolina port need not be ashamed of its third-place position, however. Its total was not far behind, and Charleston can boast of service by two container lines (Sea-Land and Seatrain) with direct service to Europe by Seatrain.

Future is open

Truth of the matter is that neither port has moved far enough ahead of its competitors to settle the issue of which port will in fact be the “Container Port of the Southeast” or “Largest General Cargo Port of the Southeast” in 1980. This question is vastly more significant than which held the lead in 1970, and each port must do all within its power to attract new cargoes out of the Midwest and develop new exporting and importing industries into the Southeast, where the cargo will become more or less captive to the region.

Port promoters and publicists must substantiate their boasts on the basis of available records, however, and this being the case, they would do well to make their spiels as follows:

Charleston: More container lines than any other South Atlantic port and the only (at this writing) scheduled direct service to Europe.

Jacksonville: Largest number of containers moving through any South Atlantic port; largest (by far) total waterborne commerce of any South Atlantic port; largest volume of coastwise and foreign cargo in the Southeast.

Savannah: The South Atlantic’s largest tonnage of general cargo export and import traffic reported by the U.S. Corps of Engineers for the year 1970. Each port has its problems, however, and the bad may as well be mentioned with the good.

Despite its proximity to the productive Piedmont section of the Carolinas, Charleston is forced to share this market region with the Port of Norfolk. Except for this, Charleston would likely be enjoying a container trade substantially larger than Jacksonville today.

Savannah was unfortunate in losing its container gantry by structural failure as it was being put through its acceptance trials last fall. It may be another year before a replacement crane can be fabricated and erected. This will cause a delay in Savannah’s container operations. Join this to the fact that Savannah is boxed in between Charleston and Jacksonville (and must share the Piedmont business with Norfolk too) and the present rosy figures lose some of their glow.

Jacksonville seems to hold the greatest future, based upon the success which Sea-Land has already developed in the port and the availability early this fall of the port’s second container terminal, this one on Blount Island. The port is confident it will be chosen for the Japanese container consortium, which will initiate direct, speedy service to the Far East next year. All this could put Jacksonville far in front.

There is one problem, and it is a serious deficiency. Jacksonville does not, at the present moment, have a large, captive general cargo trade maintained by locally based import and export merchants. For the next few years, it must struggle for business on a strictly competitive basis, winning when it provides good service and losing when it fails. Very little is locked in at Jacksonville today.

You may also like:

FreightWaves Flashback 1960: “Walk-Through” Containers Give Maximum Flexibility

FreightWaves Flashback 1963: Rail piggyback captures 9.3% of citrus movement in two years

FreightWaves Flashback 1963: Airplane displaces ship in Saturn S-IV transportation role