If weekly driver miles had remained the same since 2016, the average over-the-road truck driver in the U.S. would be making $1,247.44 per week today. Instead, miles per truck have declined for a number of reasons – electronic logging devices and detention to name just two – and despite the average pay per mile rising from 52 cents per mile in 2016 to 59 cents per mile in 2018, according to the American Transportation Research Institute, drivers are making less.

Since January 2016, miles per truck per week, according to TCA Benchmarking Indices included in FreightWaves SONAR platform (SONAR: MILTR.VCF), have fallen from 2,114.3 miles on March 29, 2016, to 1,825.2 miles as of Dec. 31. With the pay per mile increase, the average over-the-road truck driver now takes home just $1,076.87, compared to $1,099.43 at the lower per-mile rate in 2016.

Unless restrictions on driving hours are eased or significant changes to driver detention are implemented, it’s tough to envision long-term change. But Andrew Berberick and Nate Robert think there is a way to increase miles, and therefore pay, while improving efficiency for fleets and lowering overall costs for shippers.

Their idea may not be novel – they admit some larger fleets already deploy their solution – but the way they are approaching it and the opportunity they are offering to fleets is, and that is where the efficiencies can be gained.

“When a long-haul truck drives into a metro area, once they get into the city and are sitting in city traffic … that final mile of delivery is the most painful [and expensive] for drivers,” Robert explained to FreightWaves. “The pain point is felt not only by carriers and drivers but also by shippers as well.”

Berberick and Robert co-founded Baton. Baton just closed a $3.3 million seed round of funding and expects to launch its drop-zone solution in Ontario, California, and Dallas in March. The funding round was led by investment firm 8VC and includes commercial real estate giant Prologis and SVAngel as investors. (Both 8VC and Prologis are investors in FreightWaves as well).

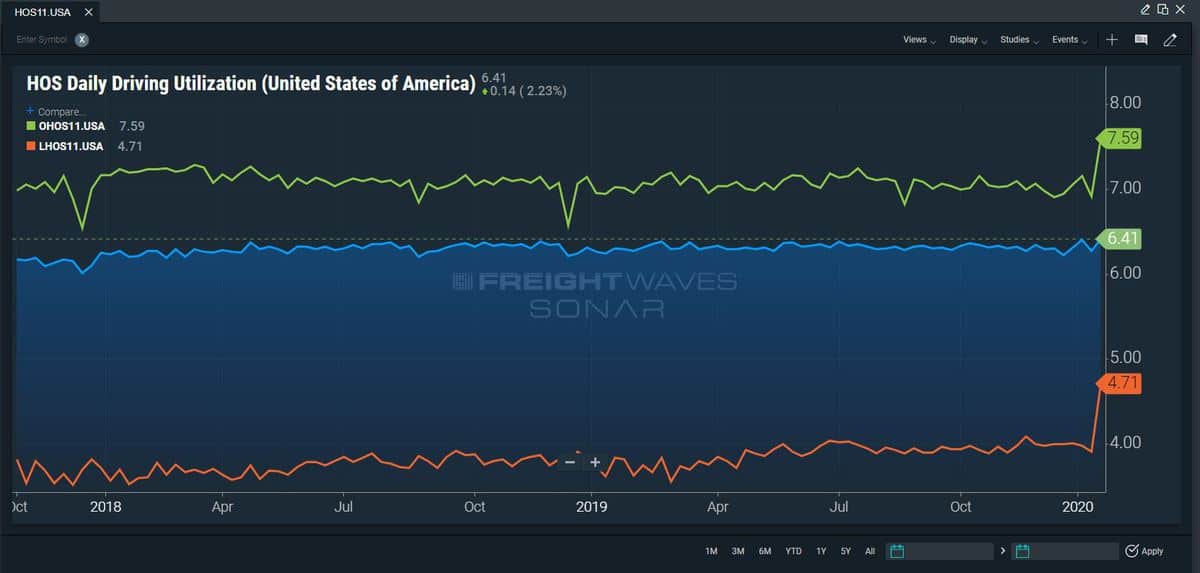

In explaining the need for such a solution, Berberick cited a Massachusetts Institute of Technology study that found trucks drivers only spend about 6.5 hours per day driving. Data inside FreightWaves SONAR shows that the average over-the-road truck driver in the U.S. drives 7.59 hours per day (SONAR: OHOS11.USA), while the average of all drivers is 6.41 hours per day (SONAR: HOS11.USA). Conversely, local drivers drive an average of 4.71 hours per day (SONAR: LHOS11.USA).

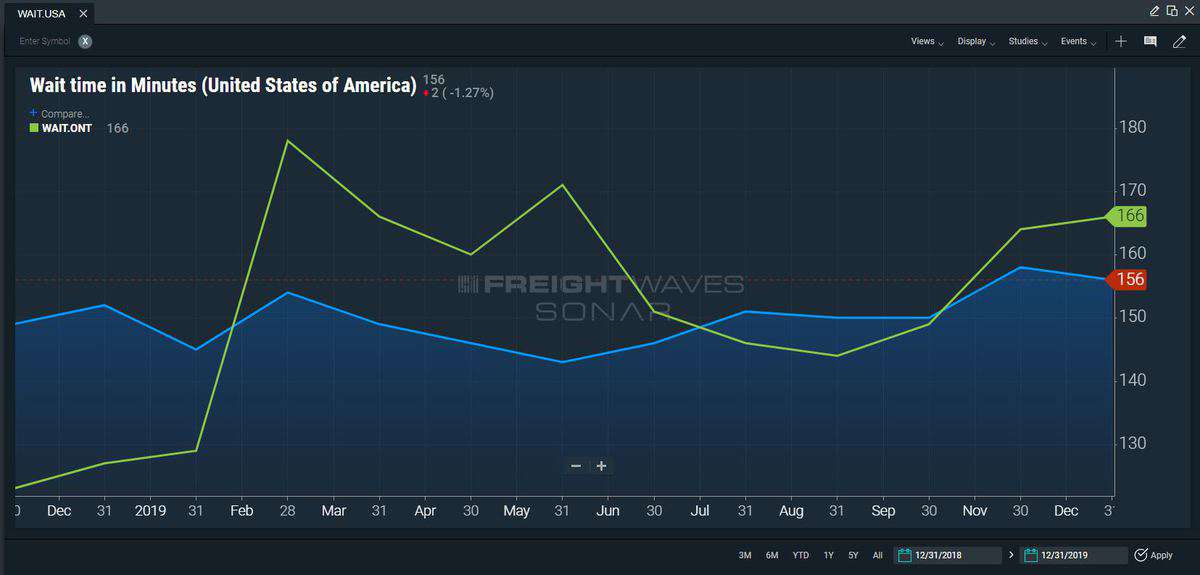

Add in detention time, which SONAR data shows at an average of 156 minutes as of Dec. 31 and is even worse in Ontario at 166 minutes (SONAR: WAIT.USA and WAIT.ONT), and it is no wonder that over-the-road drivers hate those final miles. The FreightWaves Freight Intel Group said that detention costs the industry over $1 billion a year in foregone profits and over $17,000 per truck per year. The findings will be published in an upcoming white paper taking an extensive look at detention’s true costs to the industry.

Baton is trying to change this by opening up drop yards just outside urban areas, allowing drivers to drop a trailer and quickly return to the road. Baton will handle delivery of that trailer to its final destination. According to Baton, underutilized assets cost fleets as much as $500 per day – a $350 million lost opportunity for a 10,000-truck fleet.

“What we’re building is economical today and in the future in five or 10 years when autonomous trucks come out, this will be the model,” Robert said, noting that “we think it is a driver-efficiency problem and we’re helping that by taking out the hours that are the worst part of the journey.”

Berberick said that a trucking fleet could see several efficiencies, including more miles for its drivers and more capacity to haul freight, by freeing up those hours spent waiting at facilities.

“The value for carriers here is the opportunity cost of not having that driver and asset sitting in the city,” Robert said. “It’s about getting that driver and asset back on the road so they can make more profit.”

It also could allow fleets to fine-tune specifications of their vehicles, Robert said. “The problem is that a truck has to be designed as a ‘jack-of-all-trades’ truck that not only has to operate at 55 miles per hour on the highway but be able to handle tighter [city driving],” he said.

Berberick noted that in the future, it could enable the use of more-efficient electric vehicles for the local haul and long-haul trucks optimized for highway driving.

“We’re into really gaining efficiencies. I think one of the reasons many of these efficiencies haven’t happened yet is you need everybody to collaborate.”

Andrew Berberick, co-founder of Baton

Once a trailer is dropped at a yard, the OTR driver can pick up another trailer – Baton can retrieve a loaded trailer from a local location to further improve efficiency. Baton contracts with a local fleet that handles the final delivery. Because Baton would contract with multiple OTR fleets in the area, the local fleet driver is able to drop a trailer at the destination and move on to the next job, cutting detention time to nearly zero and ensuring that driver remains busy. Berberick also said this model allows for more accuracy in hitting delivery appointments, including the ability to deliver during off-peak hours.

“We’re into really gaining efficiencies,” Berberick said. “I think one of the reasons many of these efficiencies haven’t happened yet is you need everybody to collaborate” – shippers, carriers, drivers and real estate partners.

Baton’s founders estimate between a 25% and 50% increase in asset utilization for fleets on delivery day through use of its services, and that translates into as much as 25% increase in miles driven per week for drivers.

Baton is a non-asset-based company, so working with the right partners is critical, Robert added.

“We want to make sure the local delivery network we work with is high caliber and highly vetted,” he said, and for now, that means fleets with W2 drivers. Baton is currently in talks with four of the nation’s top 20 fleets and several medium-sized fleets about participating in the early launch.

“[The reaction] has been overwhelmingly positive,” Berberick said. “When you talk about California in particular … it’s a difficult place to operate and the assumption is this is great because it allows fleets to get in and out of the area more effectively.”

Use of a drop yard can be done by any fleet, but Baton’s founders believe the combination of their technology and the ability to work with multiple fleets at a time will make their service more cost-effective than a fleet going it alone.

Berberick explained that Baton is building algorithms that will “allow us to optimize [the outcome] and allow the driver to load in the most optimal way.” The result will be better economics for the carrier, better relationships with shippers who will deal with a local provider that is able to optimize scheduling, and more money for drivers.

“There’s a trove of data about last-mile inefficiency that we can combine together to make better decisions,” Berberick said.

Baton is also building an application programming interface (API) to make the entire process seamless for customers.

All the drop zones will include automated entry to ensure security. Berberick said the hope is to eventually partner with a “valet” company that would stage trailers on the lot autonomously.

Both Berberick and Robert participated in 8VC’s entrepreneurs in residence program and worked on a number of possible logistics ideas before settling on the concept that would become Baton Trucking.

“A lot of the sales process is a relationship,” Robert said. “We have seen tech people come into the freight industry and think they can solve problems and that’s not how it works. … we see this as [using tech and people]. If you were to ask, are we a logistics company or a technology company, the answer is yes.”