The business of shipping containers by sea is getting a shakeup from a host of start-ups, promising to bring greater efficiencies to both ocean carriers, freight forwarders and their customers.

It’s still a matter of time whether companies targeting the space will last in the long run. But the firms are finding an increasing toehold in the market, particularly as e-commerce gives rise to a new shippers with little experience in ocean freight and that expect a technology-driven customer experience.

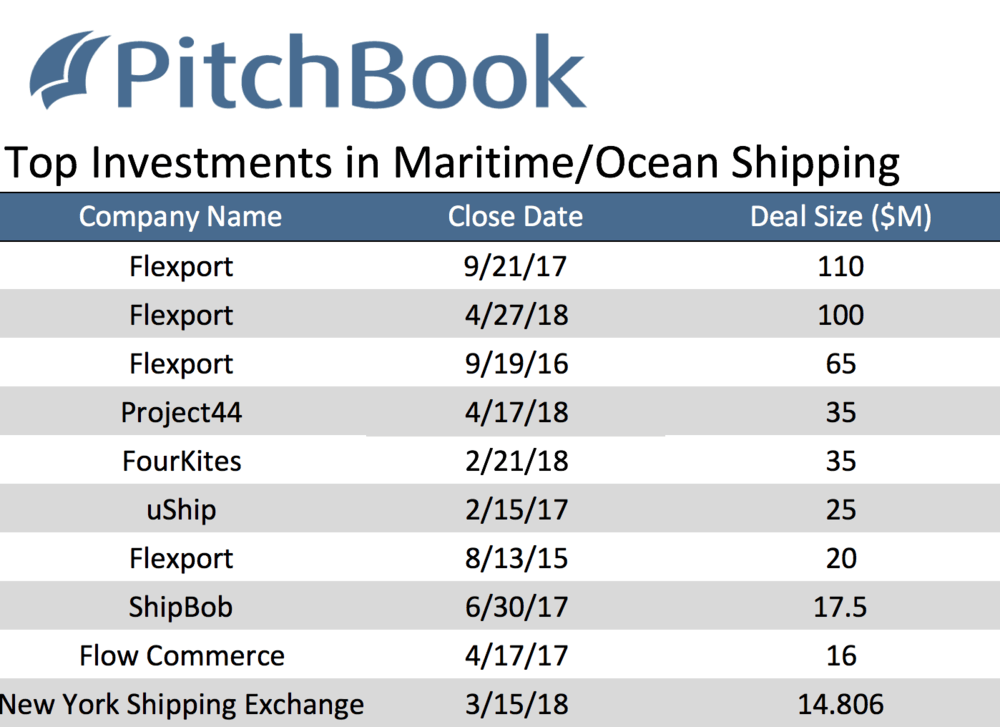

Venture capital is putting money into the space at an increasing rate. In the second quarter, total VC funding for start-ups aiming at the ocean freight market reached $138 million according to VC research firm Pitchbook, the highest such quarterly amount since tracking the space. Pitchbook’s data show $585 million going into the maritime technology space since 2013.

In a report last year on the sector, technology researcher Gartner said “ocean logistics portals” received $1 billion in VC funding over the previous 18 months, compared to half that amount in the previous five years.

The diverging figures point to the difficulty in defining a fairly broad set of companies that, in some instances, also target surface transportation.

It includes transportation management software that stitches booking, quoting, and tracking ocean freight into a desktop environment; new online platforms for trading ocean freight; and new service providers that take aim at traditional freight forwarders.

The overarching theme of these start-ups is to address costly booking delays and ease the process of container shipping.

In the old model, shippers with sufficient volume would negotiate with directly with ocean carriers for container slots. But shippers would face delays in receiving those quotes and may not even receive the slot or ship they bid on.

The other option would be to go with a freight forwarder. But shippers then face the problem of limited transparency in quoting and tracking their goods.

Just as consumer travel is now dominated by web-based services, Gartner says the start-ups aim to use a web-based portals that “address the time-consuming process of booking ocean freight into a near instantaneous consumer-like experience.”

Gartner says the new web-based portals may or may not offer better rates than can be found through a forwarder, but “this model does save time.”

“It allows the shipper to respond quicker to both internal colleagues and customers, who may be waiting on the information for sales or customer service reasons,” Gartner says.

Ocean carriers themselves are moving in the direction of these new start-ups. Maersk plans to use a software platform from CargoSphere, a now 19-year old company acquired last year by WiseTech Global, to ease the process of distributing rate information to customers.

The world’s largest shipping line also announced last week that it would to start offering container space for trans-Pacific sailings on the online freight trading platform New York Shipping Exchange (NYSHEX).

Other carriers are also responding to shipper demand for more convenience. Hapag-Lloyd will introduce this September an online service, Quick Quotes, for shippers to receive a container shipping quote immediately. Last year, Maersk introduced a similar feature through Twill, the digital freight forwarding subsidiary of its Damco logistics unit.

Here, then, is a non-comprehensive look at what some of the new companies aim to do in ocean logistics:

Freightos

Freightos, which has raised $50 million in venture funding, provides software for freight forwarders and shippers to manage and automate both ocean and surface shipping price quotes, a once highly manual process of entering and stitching rates and quotes from spreadsheets, emails and other sources.

Freightos’ software also calculates optimal routes for door-to-door shipments based on those rates.

Along with rate management, Freightos aggregates ocean shipping rates, allowing comparison shopping for container shipping. Freight forwarders can then post offers for ocean shipping online and shippers can book those slots through the Freightos platform.

Freightos is “like an Expedia or Kayak” for freight forwarders,” said chief executive Zvi Schreiber. “If you have a container that you want to ship to Chicago, you can see different offers and pricing and do some comparison shopping.”

Schreiber says comparison shopping for ocean freight was never easy due to non-standardized rates and forwarders being reluctant to share price information. But forwarders are recognizing they have to move in a new direction.

Schreiber says freight forwarders are “are a little nervous about transparency. But they see transparency is coming anyway.”

“The good thing is that we are enabling the freight forwarders, not disrupting them,” Schreiber said.

As for shippers bidding on slots, Schreiber says the Freightos platform initially attracted small, Amazon-type vendors that needed to ship a container on a spot basis, and less so on a recurring basis.

But he says the Freightos platform is starting to get shippers that are moving “hundreds of containers per month.”

Along with its main customer base of freight forwarders, beneficial cargo owners such as retailer Marks and Spencer and Sysco Foods are using the platform. Likewise, an ocean carrier is also using the Freightos platform to market container slots directly.

Schreiber says Freightos was born out of his own frustration as a shipper trying to book ocean freight. Prior to Freightos, he was the chief executive of an LED light manufacturer and was trying to ship freight from Shenzhen to the US and Europe.

It would take three or four days to get a quote for a container slot due to the back-and-forth with the carrier and the forwarder, Schreiber says.”I was shocked by how manual the process was.”

Moreover, once various surcharges were tacked on, the actual rate may not match the quote, the transit time could not be guaranteed, and the cargo might even be rolled onto another ship.

“It was almost like the days when it was much more common for a flight to be overbooked and you could get bumped,” Schreiber said.

NYSHEX

Gordon Downes, the chief executive of New York Shipping Exchange, shared the same frustration with how the container shipping industry worked, but from the perspective of the ocean carrier.

A 12-year veteran of Maersk, Downes recalls working with a shipper to set up a new vessel service involving several container ships. But once the service began, the shipper only sent half the level of cargo they originally committed to.

“We expected to have full ships and half the cargo wasn’t there,” Downes said. “It’s very frustrating after all that work putting a contract together.”

But ocean carriers, too, also have commitment issues with regards to shippers. They may provide quotes for slots, but those slots may not be available when the container is ready. Even when a slot is officially booked, ocean carriers may change vessel, origin point and delivery times on shippers with little notice.

NYSHEX aims to create a forward contract for container slots that are the equivalent of a non-refundable airline ticket, Downes says. The online platform, which went live last August, allows ocean carriers to post offers for container slots on specific ships or sailings with guaranteed origin-destination pairs and transit times. NYSHEX gets $5 per teu traded on its platform.

The shippers then enter into a service contract that is filed with the Federal Maritime Commission. NYSHEX also uses data from the ocean carrier and shipper to monitor that each party has fulfilled their end of the contract, with any disputes settled through maritime arbitrators.

Downes says contracts entered through the NYSHEX platform have almost 100% reliability in terms of fulfillment, compared to a 76% level of reliability in contracts entered directly between shippers and ocean carriers. Carriers are offering sailings up to six months out on the NYSHEX platform, providing them with greater visibility on their forward demand.

NYSHEX ‘removes the counterparty risk of a shipper not coming through with a container or a carrier rolling over a container to a later sailing,” Downes said. “We can basically monitor the contract and make sure what is promised is delivered.”

Major ocean carriers including CMA CGM, Hapag-Lloyd, Mitsui OSK Line and Orient Overseas Container Lines are backing the company, which has raised $13 million in its first series of venture funding.

The amount of container space those carriers and others are offering on NYSHEX is just a small part of their overall capacity, and naturally varies depending on how much slot space has already been sold.

The NYSHEX platform is a “complement to the service contract and a substitute for a spot booking,” Downes said.

But NYSHEX plays an important role in helping balance the market Downes says, particularly now during the start of the peak shipping season. Most of the slots offered on NYSHEX are for the trans-Pacific trade, the busiest in the world.

Shippers with service contracts with an ocean carrier may have to scramble for extra capacity, and face the prospect of contacting multiple carriers individually for a quote.

LIkewise, ocean carriers that may have too much slot inventory due to a lack of committed containers will be able to find shippers to fill those slots more efficiently.

With Maersk now marketing some of its trans-Pacific slots on the platform, the depth of the NYSHEX’s market will grow.

“There is all this variation in the market during the peak season,” Downes said. The spot market for shipping “is like the wild west when it comes to reliability, which can put a supply chain at risk.”

Flexport

Sanne Manders, chief operating officer of Flexport, says it’s sometimes unclear how to describe Flexport.

“I’d like to say we are a technology company in the freight forwarding industry,” Manders said. “But others say we are a freight forwarder with much better technology.”

Manders acknowledges that freight forwarding is a mature industry that has worked pretty well over the last two hundred years. There are already thousands of participants that have a Federal Maritime Commission license to ship ocean freight. But that doesn’t mean the industry model cannot be changed, Manders says.

Traditionally, shippers would face dealing with a long chain of people, from freight brokers to customs brokers to ships agents, to move their containers. For a shipper to get a simple answer as to where a container might be required a long series of phone calls and delays that most customers would find intolerable in other industries.

Manders says Flexport introduces a much simpler customer experience for shippers, with one key account manager dedicated to each customer account.

“Most freight forwarders typically worked within functional silos” Manders said. Flexport’s customers “never have the Comcast experience.”

Likewise, Flexport brings shippers’ more visibility into their transactions with technology, including a desktop dashboard for tracking containers and providing them analytics for their supply chain.

“Where the differentiation is for Flexport is the technology that provides the visibility into the supply chain,” Manders said.

Manders says collecting data on container movements is “still a challenge for all the freight forwarders as it is for us” due to differing technology standards and capabilities among all those involved in the supply chain. But Manders says ocean carriers and others are becoming more cooperative due to customer demand for better visibility on shipments.

The supply chain has “typically not been very transparent, Manders said. “”Now you can see how the whole supply chain is moving and the status of the cargo.”

Flexport is targeting all types of shippers for its services. But its early success has been with newer, e-commerce-type companies, particularly those with high inventory replenishment needs such as fashion and electronics.

Its biggest trade lane has been the trans-Pacific, which is dominated by C.H. Robinson and Expeditors International. While the largest forwarders are moving anywhere from 300,000 to 400,000 teu of containers, Manders says Flexport is moving above 120,000 teu.

“Our bread and butter is the middle market companies,” Manders said. “They are not in the Fortune 500, but a notch below.”

But the incumbents are not standing still in this space. Manders says Maersk’s Twill online forwarding service is modeled after Flexport and is likewise targeting e-commerce and Amazon-type merchants.

Kuehne and Nagel, Expeditors and C.H. Robinson are also investing in new technology to attract e-commerce focused shippers.

Flexport is responding by adding more physical assets. Along with more warehouse space, it will soon add its second chartered Boeing 747.

Freight forwarders “are copying us in terms of technology, so we are copying them in building our physical network,” Manders said. “This is what the race will be. There is no clear winner yet, and it’s going to be an interesting to see what happens over the next decade.”