CLEVELAND — In a room full of battered transportation and logistics companies laboring under the continued drag of a historically weak freight market, it would have been easy to declare that the second half of 2023 will be better for carriers and brokers than the first half.

But that was not the message from Craig Fuller, founder and CEO of FreightWaves, appearing at the company’s Future of Supply Chain event. Fuller was interviewed by FreightWaves’ Zach Strickland.

An overall negative outlook came with one caveat: It’s tough to figure out what’s going on. “It’s harder to understand and draw any conclusions about the state of where the markets are headed than at any moment in time since FreightWaves began,” Fuller said. “The markets are as opaque as they’ve ever been.”

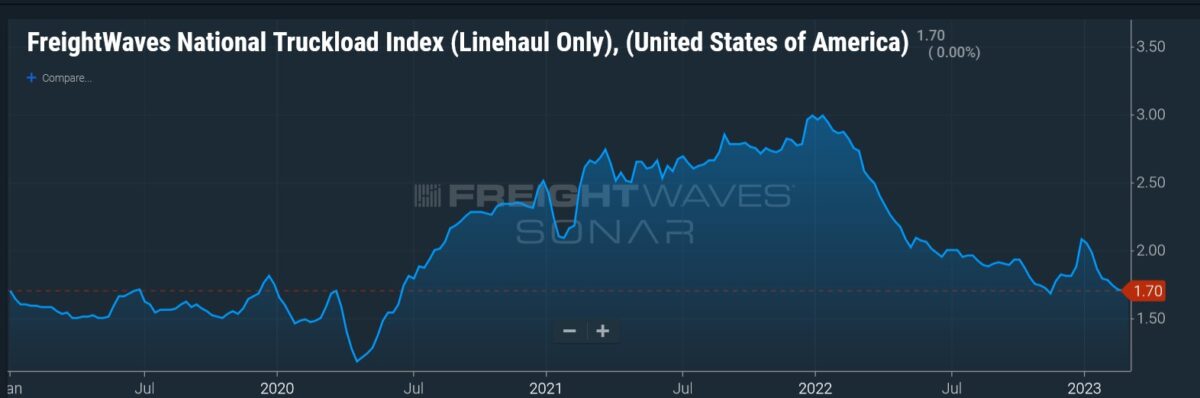

Fuller noted that based on the NTIL.USA data series in SONAR, which tracks spot freight rates net of fuel, the current market is right about where it was during the freight bear market of 2019. But the problem, he said, is that costs for things like labor and maintenance are probably about 30 cents per mile higher than in 2019. “On a cash flow basis, the carriers have lost 30 cents per mile in cash,” he said.

Combine that with the fact that the number of carriers is up about 25% since 2019, according to the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration.

“So in order to see a reset in the rate environment, you fundamentally have to have one of two things happen,” Fuller said. One would be a loss of capacity. The other would be “you need a surge in freight.”

Demand for goods in recent years was pumped up by federal stimulus tied to the pandemic, Fuller said. “But I have a hard time believing Congress will get anything passed to drive stimulus.” And given that the Federal Reserve policy is to tighten monetary conditions, the landscape for federally driven demand growth is lacking, Fuller said.

Balancing the market will need a “churn [of] capacity before you see any level of stability,” Fuller said. But one silver lining is that there “is an argument to make that the market cannot go any lower.” Rates are low enough that “carriers won’t take freight here because they lose money and we may very well be near a bottom.” But Fuller added: “I’m not suggesting there’s going to be a sudden surge.”

Spot truckload rates as measured by NTIL.USA opened the year at $2.10 per mile. That sank to as low as $1.49 on May 12 but has since rebounded to $1.62.

Fuller said a recent study by J.P. Morgan put the average breakeven cost per mile for truckload at a range of $1.56 to $1.90 per mile.

Capacity reductions through bankruptcies are not happening at a level that might be expected, Fuller said: “It just tells me that a lot of these guys who are hanging on probably really built up their balance sheets during the COVID economy, and it may be awhile before we see significant wholesale bankruptcies.”

But blaming the current market on oversupply ignores “the demand situation,” as Fuller called it. SONAR’s Outbound Tender Volume Index is largely flat from where it was at the start of the year.

But that is data for the truckload business. Adding to the demand argument, Fuller said, is that the numbers published earlier this month by various LTL carriers on their volumes in May, some of them reporting year-on-year double-digit percentage declines, reflect the fact that demand is a problem for the market as well as the supply of carriers.

Capacity in LTL, given its high barriers to entry, doesn’t have the “boom-and-bust cycle” that is prevalent in truckload, Fuller said. “So this is telling me that our problems with the freight market are not strictly related to a problem of overcapacity but rather a problem with demand,” he added.

Looking for a second-half turnaround already is fighting the calendar. June tends to be a strong month, Fuller said, but there haven’t been significant signs of an upturn. “We’re already dipping into July,” he said. “July is actually a really difficult month.”

Some of the arguments in favor of a second-half surge are based on a historical view that freight markets run in a three-year boom-and-bust cycle, Fuller said. With the bust having started more than a year ago, it would be half over — 18 months — in the fall. “But we’re in a different monetary regime,” he said of higher interest rates. The most recent cycle, from the bust of 2019 to the strong pandemic market, “was based on very low interest rates. We are in a different economy now.”

The hourlong fireside chat touched on several other observations about the freight market.

- A restocking of inventories as a boost to the freight market is unlikely. “If you’re a retailer or a wholesaler and you have access to capacity and you have access to product, you don’t feel a need to have inventory on hand because it’s available,” Fuller said. Additionally, “everyone is worried about their cash positions.” That means that capex expenditures will be trimmed and “that cautious nature is going to start to play out.”

- Shippers are very much in the driver’s seat. Carriers will “want almost every load they can get their hands on,” Fuller said, echoing statements by Heartland Express CEO Mike Gerdin (NASDAQ: HTLD) at an investment conference in New York earlier this month. With that stance in place, shippers “will have an enormous amount of power to drive down rates, and I don’t see that changing because it would take an increase in demand or a drop in capacity.”

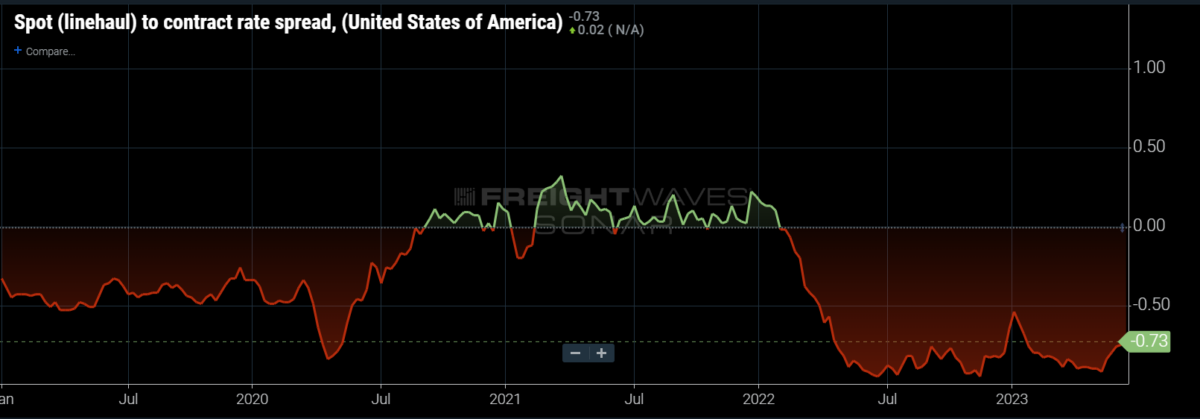

- The difference in contract and spot rates, per SONAR data, is at historic levels. But reiterating his points that the gap should return to more historic ratios, which means either a drop in contract rates or an increase in spot rates, Fuller said the former was more likely. Many current contract rates were negotiated when the market was higher, “and as these older rates burn off, and shippers are able to secure capacity, then we will see a continued decrease of contract rates.” But contract rates are “just stubbornly slow coming down in” while spot rates are reacting quickly to market conditions, so the reversion to norm might not be rapid.

- With the Outbound Tender Reject Index in SONAR below 4% consistently since mid-January, the question of what number signals a rebound or at least some stability came up. Both Fuller and Strickland agreed that a recovery couldn’t be seen on the horizon until the OTRI reached and stuck around 6%.

More articles by John Kingston

State of Freight for March: Bullish signs amid mostly bearish news

Five takeaways: Fuller and Strickland review state of the freight market